September 30th: Truth, and Reconciliation

St. Matthias’ was officially founded as a mission of St. George’s, Place du Canada, in 1873, which means our community is 150 this year! For the next 12 months, we’ll be diving into the archives to shine the spotlight on particularly interesting parts of our history.

Residential school students performing “The Huron Carol” for a St. Matthias’ Christmas party in 1971

Beginning in the 1830s, the Anglican, Roman Catholic, and Methodist churches set up boarding schools for Indigenous children that would become an important part of federal policy after Confederation. In 1876, Canada would sign the Indian Act into law; the 1920 revision of the Act made it compulsory for “Treaty-status” children from 7-15 years old to attend a residential school. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has reported that the schools as a whole were “a systematic, government-sponsored attempt to destroy Aboriginal cultures and languages and to assimilate Aboriginal peoples so that they no longer existed as distinct peoples.” The last of these institutions closed in 1996. Although these schools didn’t warrant any mention in Vestry reports over the decades, St. Matthias’ was among the many Anglican churches across Canada that contributed financially to their mission.

The children in the above photo were students at La Tuque, a short-lived Anglican residential school in northern Quebec (1963-1978). In 1971, when the photo was taken, the school had been run by the federal government for almost three years, although ties with the Anglican church were clearly maintained, as the principle remained an Anglican priest until the school’s closure. Former students participated actively in demolishing the building in 2006 – and their testimony explains why. Paul Dixon, who penned this CBC article in 2022, may have been one of the students performing at St. Matthias’. Diane Bosum, whose audio testimony appears halfway through the article, may have been another.

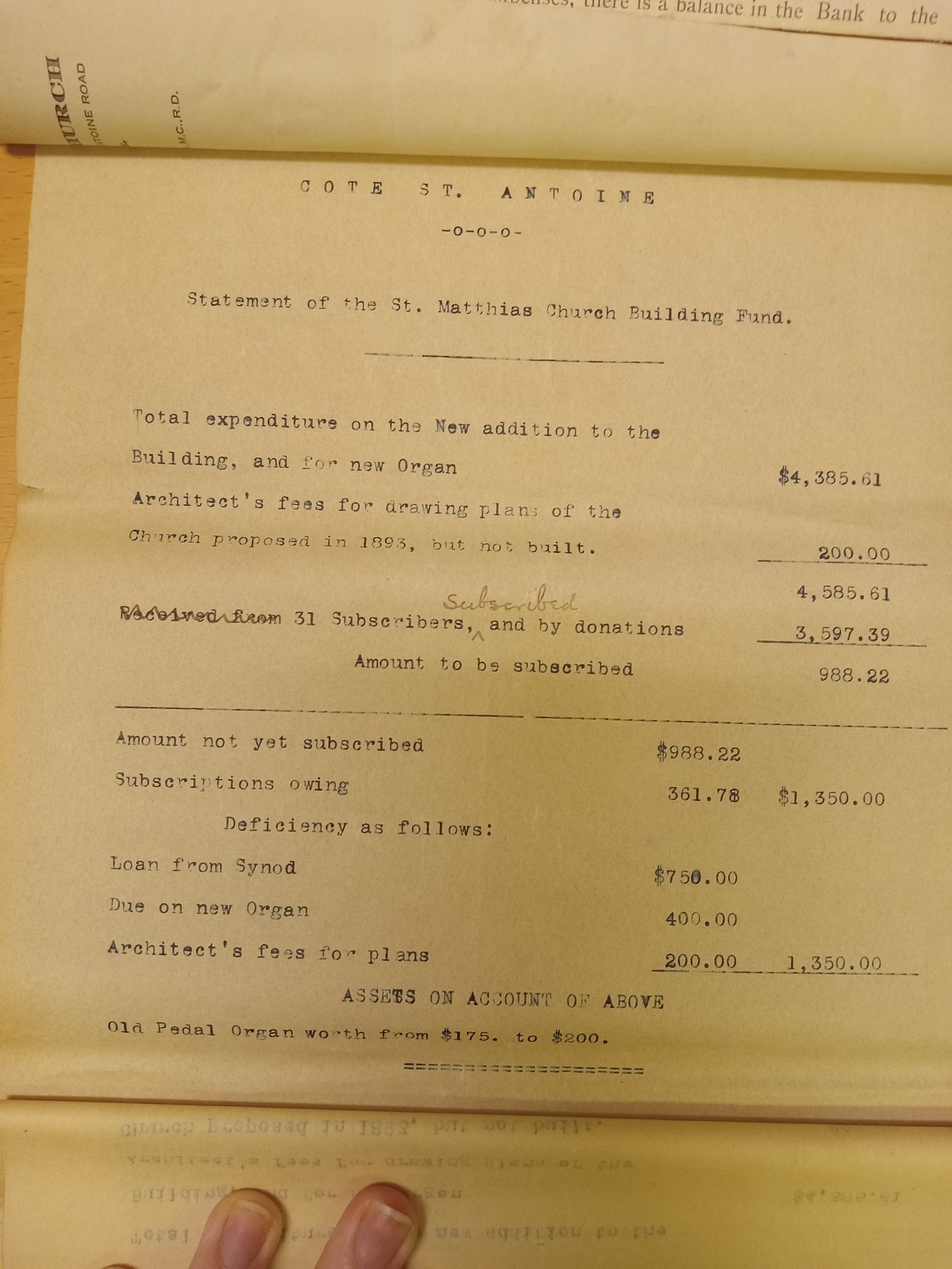

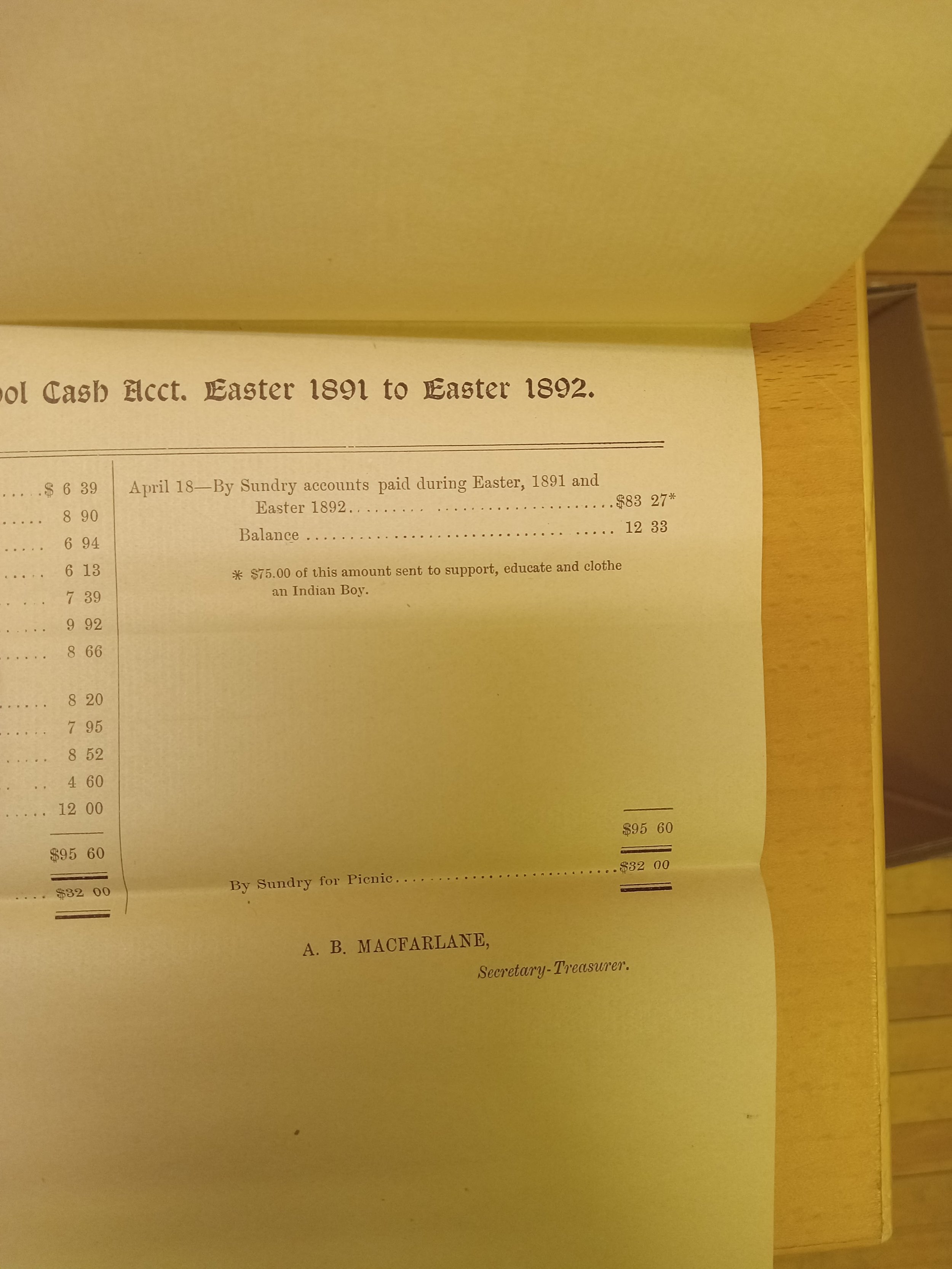

If we turn back the clock, we can see residential school support almost from the very first. St. Matthias’ 1888 Balance Sheet, approved by Vestry at Easter that year, contains a line right at the very bottom that notes that the Sunday School collection for the past year had gone to support a student at Shingwauk. The note appears, in later Balance Sheets, under the Sunday School’s own financial statements; by 1892, it was $75, over $2000 in today’s money. The Shingwauk Indian Residential School was a joint operation of the Anglican Church of Canada and the Government of Canada, founded in 1873 – the same year as St. Matthias’ – in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. It replaced an Anglican missionary school at Garden River First Nation and was destroyed by fire six days after it opened for the first time. The second building opened in 1875, the same year as St. Matthias’ original building. It would not have running water until 1935, the same year that St. Matthias’ parish hall was built. Shingwauk’s students engaged in manual labour half of every day; education was reported to be sub-par and abuse and neglect were prominent. It continued to be operated, until a year before its closing in 1970, by the Anglican church. Its cemetery contains the graves of over 120 students, many unmarked, and a site search for further unmarked burials began in 2021. Well into the 1890s, St. Matthias’ would also continue to support the Diocese of Algoma, who owned the land Shingwauk occupied.

Throughout the decades, references in Sunday School and Association of Women’s financial statements to a number of societies connected with the Missionary Society of the Church of England in Canada, including the Montreal-based Fellowship of the West, should be understood as money potentially invested in residential schools. The MSCC funded a wide range of missions across the globe, but were also directly involved in management of Anglican residential schools in Northern and Western Canada. Donations to various Bible societies subsidised Bibles being distributed to residential schools, some of which were subsequently sold as fundraisers. It’s important to be clear that St. Matthias’ records don’t show that we designated funds for residential schools – although they also don’t show that we didn’t – and many of the places Matthians have sent money over the past 150 years have had a wide range of services they provide and publics they serve. It is entirely possible that the donations we see all went to other projects run by the recipients. And we cannot know how much of St. Matthias’ contributions to Diocesan mission funds ended up in residential schools as well, at least not until the Diocese examines its own records. But it is more than likely that a lot of our mission budgets over the years were part of keeping the lights on, literally and figuratively, at institutions of cultural genocide.

It is tempting to see the absence of specified donations through many of our budgets as evidence that St. Matthias’ did not consistently support residential schools. The photograph at the top of this page suggests, however, that the church was enough of a supporter to warrant a performance by the children in that photograph. La Tuque was in the Diocese of Quebec, not the Diocese of Montreal, so the connection to St. Matthias’ would have been more direct than simply sharing a diocesan connection. It is also tempting to say “no one at the time knew any better,” but with government officials like Peter Bryce sounding the alarm from early on, we know that the information was out there. Churches like St. Matthias’ chose to trust that the Anglican church that treated them well would also treat Indigenous students in its schools well. We are allowed to mourn that we misplaced our trust, as well as our treasure, even as we understand that we certainly should have known better by Christmas 1971, nearly 50 years after Peter Bryce published “The Story of a National Crime” and almost 70 after his first report on the horrific conditions endured by students.

Although in recent years we have participated in PWRDF advocacy for Indigenous communities like Pikangikum, and St. Matthias’, Igloolik, is now an autonomous parish rather than the colonial mission it was when we sponsored its building, it is important to grapple with the legacy of our gift-giving. On this National Day of Truth and Reconciliation especially, it is incumbent upon all of us to become familiar with the TRC Calls to Action, and to ask how we might as a community, in confronting the truth about our past, begin moving toward reconciliation.