September 24th: Stewardship

St. Matthias’ was officially founded as a mission of St. George’s, Place du Canada, in 1873, which means our community is 150 this year! For the next 12 months, we’ll be diving into the archives to shine the spotlight on particularly interesting parts of our history.

The balance sheet from the 1888 Easter Report, annotated to reflect figures updated between the printing of the report and its presentation.

The earliest documents we have in our archives are financial ones, and they are certainly the most numerous as well. In the 1880s and 90s, when the fiscal year began at Easter, the wardens produced yearly financial reports, with notes from themselves highlighting particular income or expense lines, which were the main way that most people in the parish could see how we were keeping afloat. The tone of these early notes is a grateful one, as by and large the books balanced and St. Matthias’ was affirmed in its decision to be a “free seat church.” This parochial model meant that, to attend, one did not need to buy a seat; one simply gave via envelope on a Sunday morning. Although this would become the prevailing model of Canadian Anglicanism, at the end of the 19th century it was considered something of a risk. But this balanced budget would not last long, and soon St. Matthias’ found itself counting pews – and pew-sitters – and coming up with a much larger number than the number of those who contributed financially.

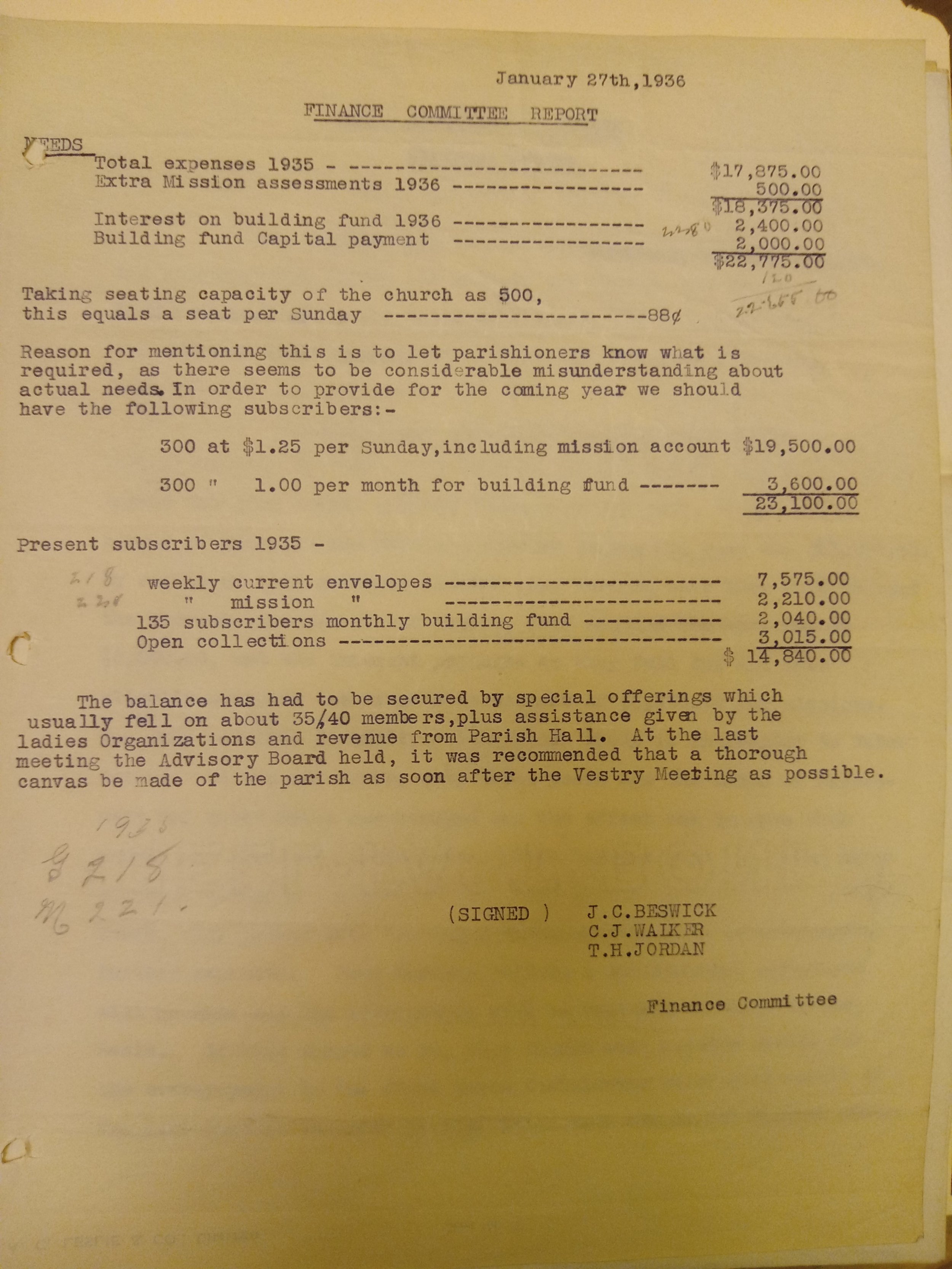

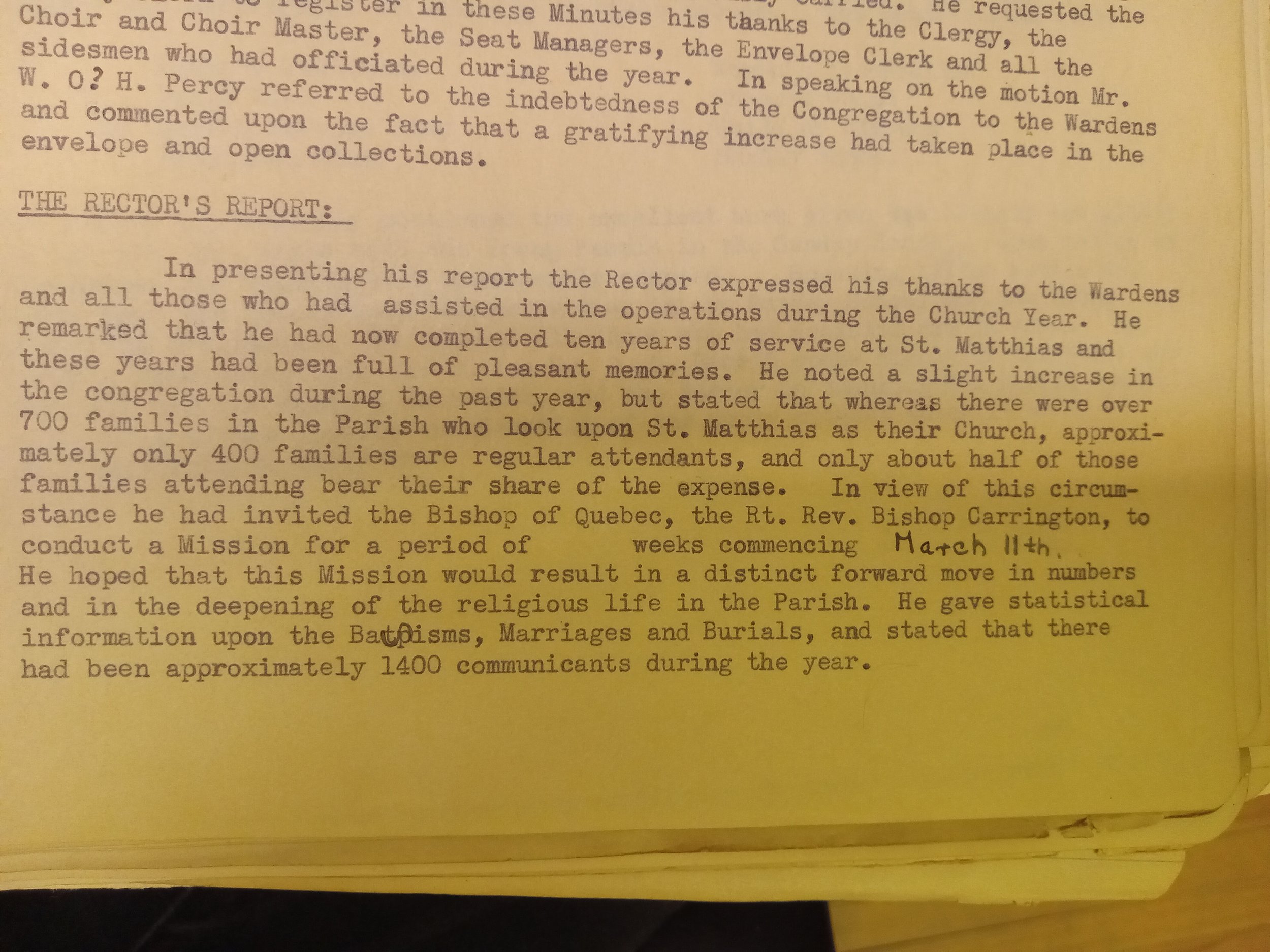

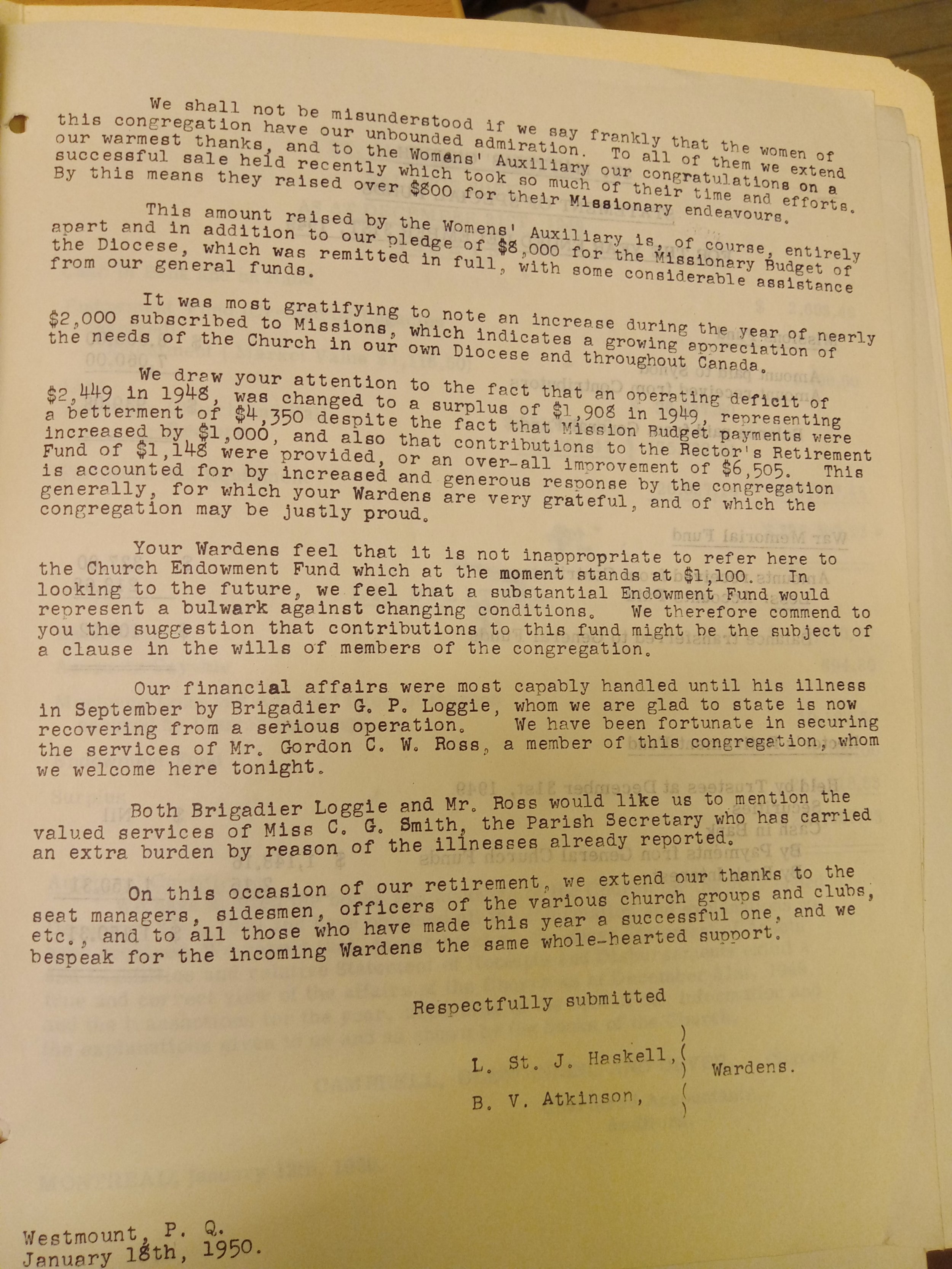

By the beginning of the 20th century, regular giving was in decline, although the church was seeing steady income to the building fund. As membership grew, without the requirement to purchase one’s pew the weekly offering revenue stayed more static than it really should have. A finance committee report submitted at the beginning of 1936 paints the picture starkly: with nearly $23,000 (today: nearly $495,000) of annual expenses and about $15,000 (today: $322,000) of annual revenue, the gap needed to be closed each year “by special offerings which usually fell on about 35/40 members, plus assistance given by the ladies Organizations and revenue from Parish Hall.” For a church that could seat 500 at each of its three Sunday services, this was hardly acceptable. And despite being informed by the Finance Committee of what it would take in terms of weekly giving to balance the budget, the situation did not improve; reflecting on 1937, Rev. Gilbert Oliver noted that of the 700 families on the parish rolls, only about 200 “bear their share of the expense.” But although Rev. Oliver took the initiative to invite the Bishop of Quebec to lead a parish visit effort later that spring, the Wardens’ Report the following year notes a deficit of a little over $500 (today: a little over $10,000) and an increase of “money raised from all sources” of less than $600 (today: about $12,500). “We should,” the report concludes, “be able to do better than have one-half of the families of the Parish supporting this Church.”

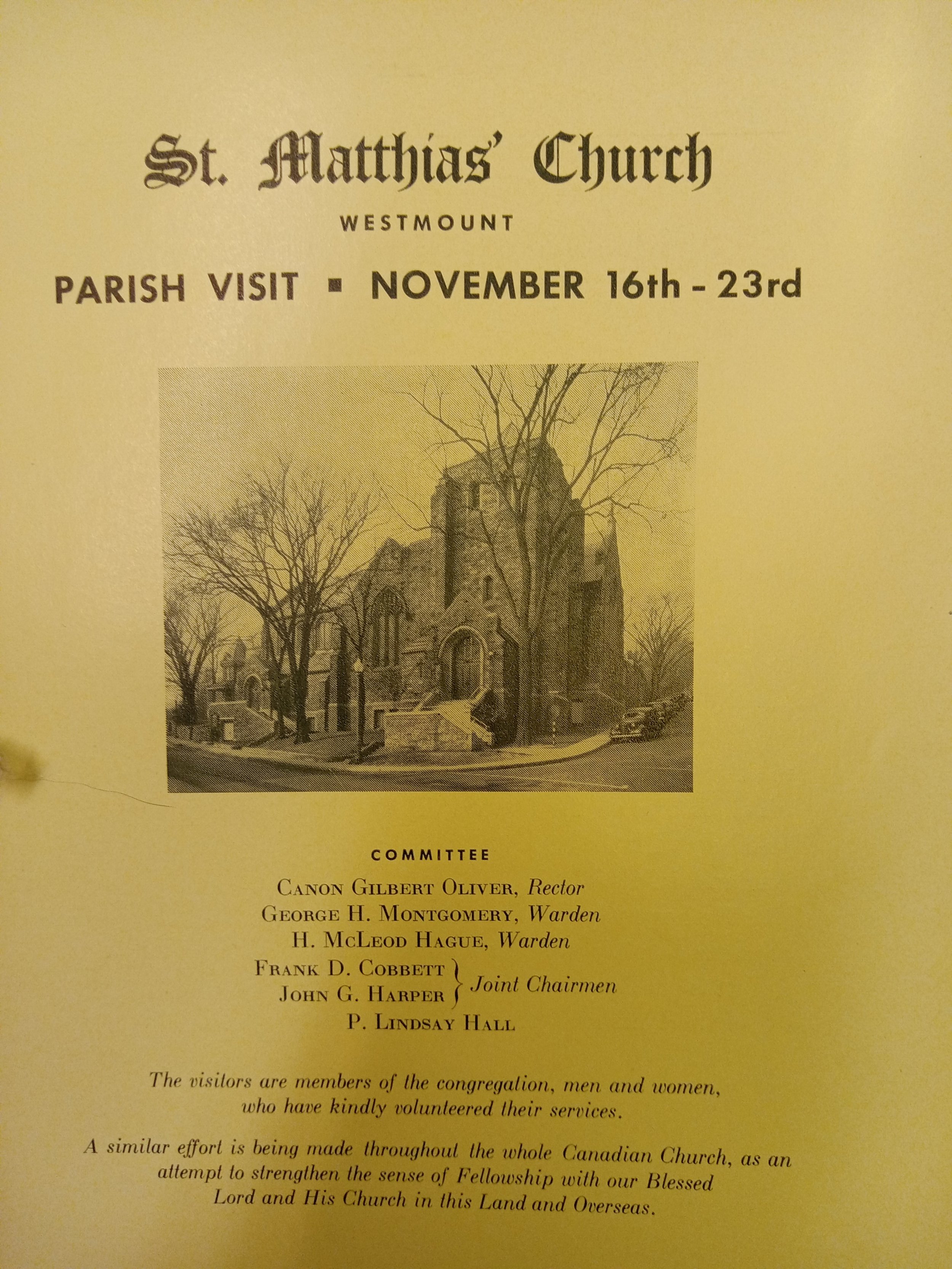

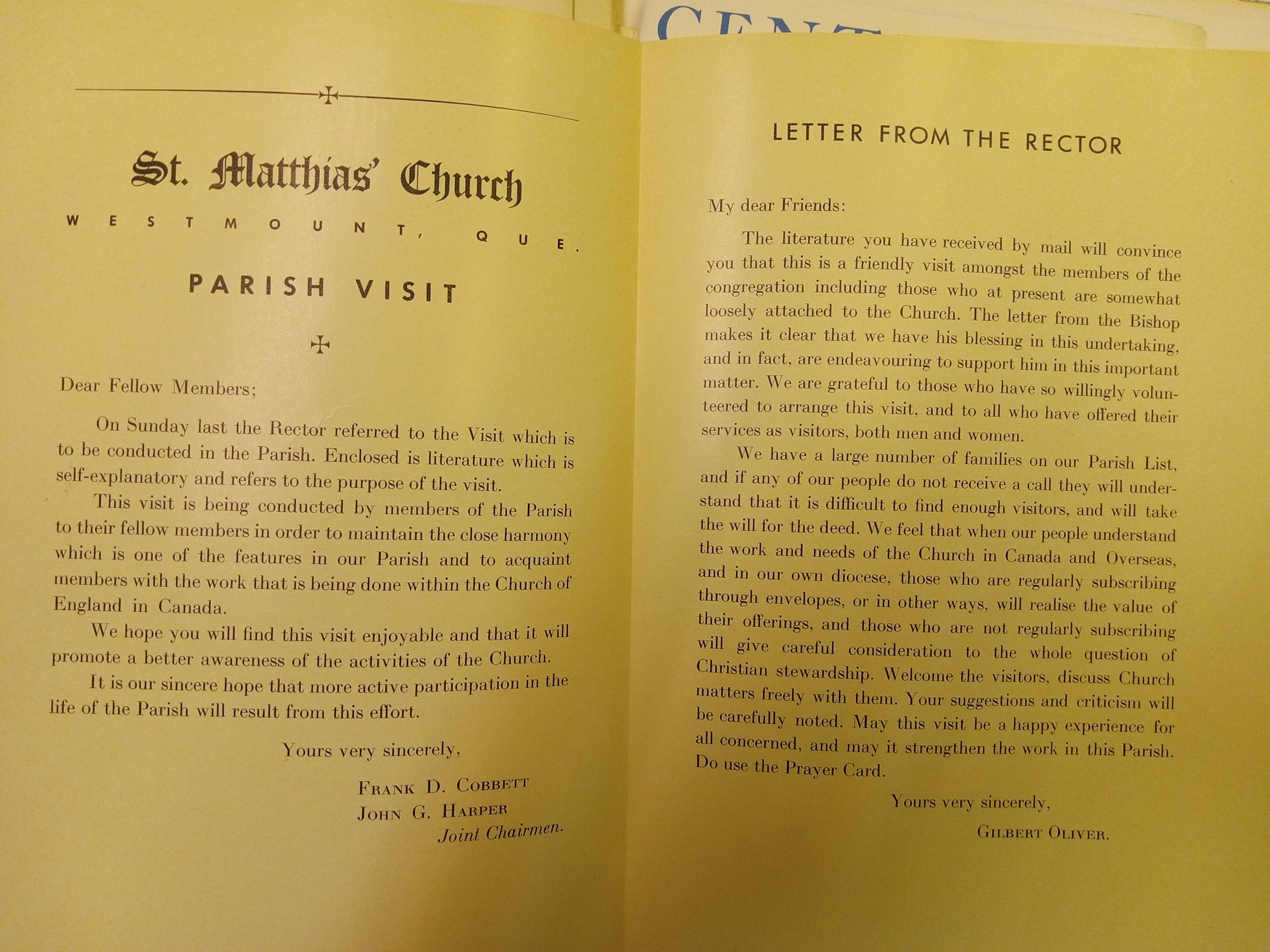

The parish visit led by the Bishop of Quebec resulted in only one trace in our archives: the base brochure, which features a photograph of the church taken shortly after the completion of the parish hall in 1935, notes from the Wardens and the Rector, and two prayers for the church. It also contains references to literature “you have received by mail” on the activities of the church and the purpose of the visits. The underlying logic of the campaign seems to have been that, as people “somewhat loosely attached to the Church” became more aware of what, precisely, the church had to offer, and the many missions it was supporting, they would “realise the value of their offerings” and “give careful consideration to the whole question of Christian stewardship.”

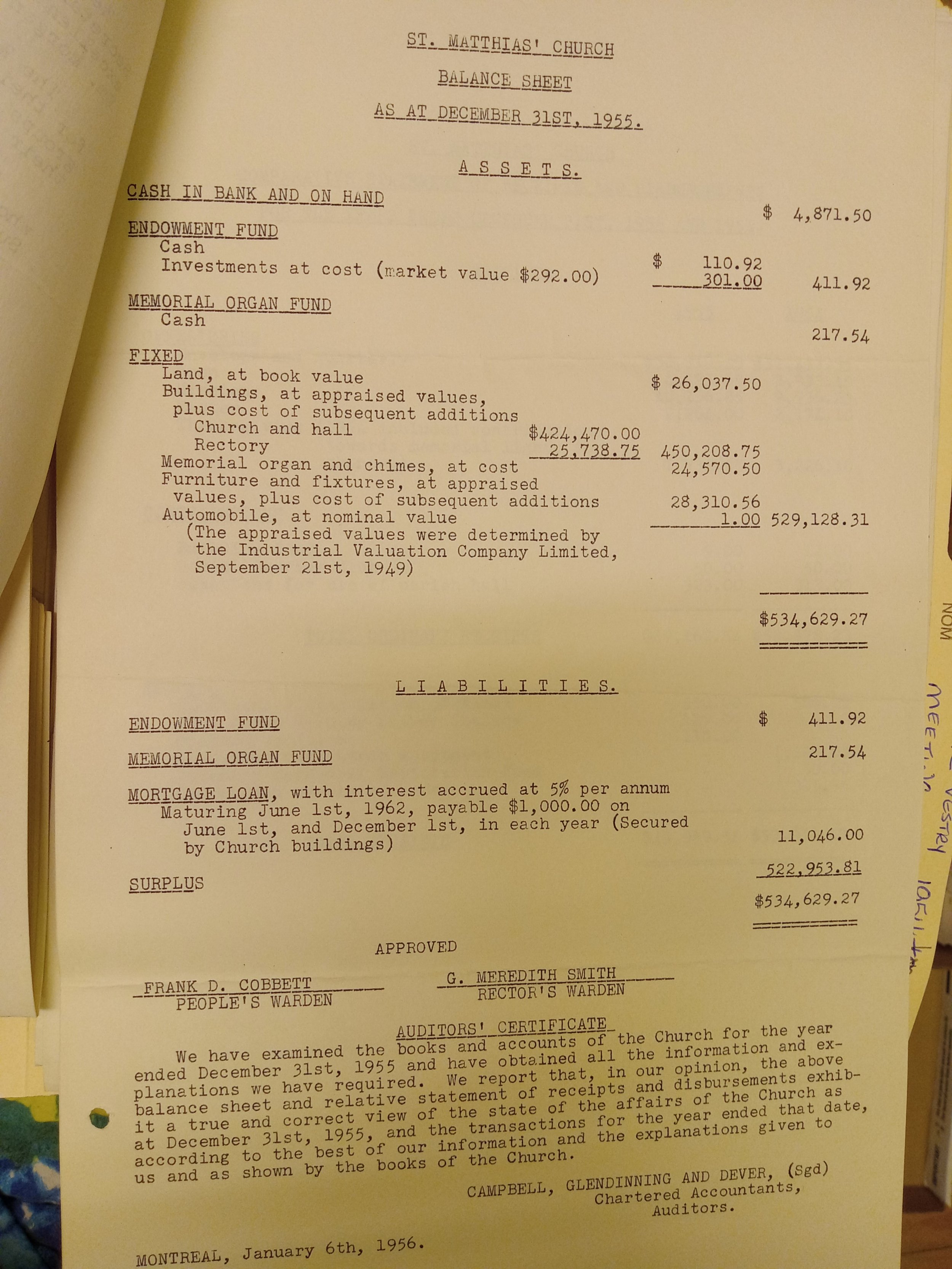

Although the war years proved slim as well, for obvious reasons, and the loan taken out to complete the parish hall had to be extended well into the 1950s, 1949 ended with a surplus of nearly $2000 (today: a little over $26,000). The documents we have for these decades show a pattern: almost as soon as St. Matthias’ finished paying off one major expense (the extension of the old church in 1888, the building of the new church in 1910, the building of the parish hall in 1935, the installation of a new organ in 1951), the congregation would embark on another. While pledges for these campaigns were often good, operating expenses seem to have fallen more often by not to the wayside, leaving Wardens tearing their hair out as they tried to make ends meet. The 1960s may have been more balanced, without a major project to occupy church finances. We simply don’t know: our archives have a decade-long gap in our archives between 1959 and 1970.

Of course, in the early 1970s, a new major project was conceived: the building of our current organ for the parish’s 100th anniversary in 1973. This fine instrument deserves its own post, but in financial terms, it meant that St. Matthias’ was back to its old tricks of raising money primarily for special projects, and by the end of the decade, something simply had to be done about financing day-to-day operations. Enter New Horizons, a campaign that would run from Lent 1976 to the end of the year and would involve every family on the parish list receiving a fundraising visit. In reporting on the campaign in October 1976, Gordon Dorey noted that there were many pledge cards still outstanding, meaning that many families on the parish list had not made any kind of financial commitment. Speaking to Vestry a few months later. Rev. Jack Doidge celebrated the faith of the parish as reflected in their giving, but challenged them to consider: “Are we the Body of Christ – or – just a group of people who go to Church occasionally?” Similarly, the Wardens noted that while the finances had stabilised, the fundraising goal had not been reached (possibly because over 100 families had not been visited) and as a result urgent masonry repairs had not been made – a refrain that continues to the present day.

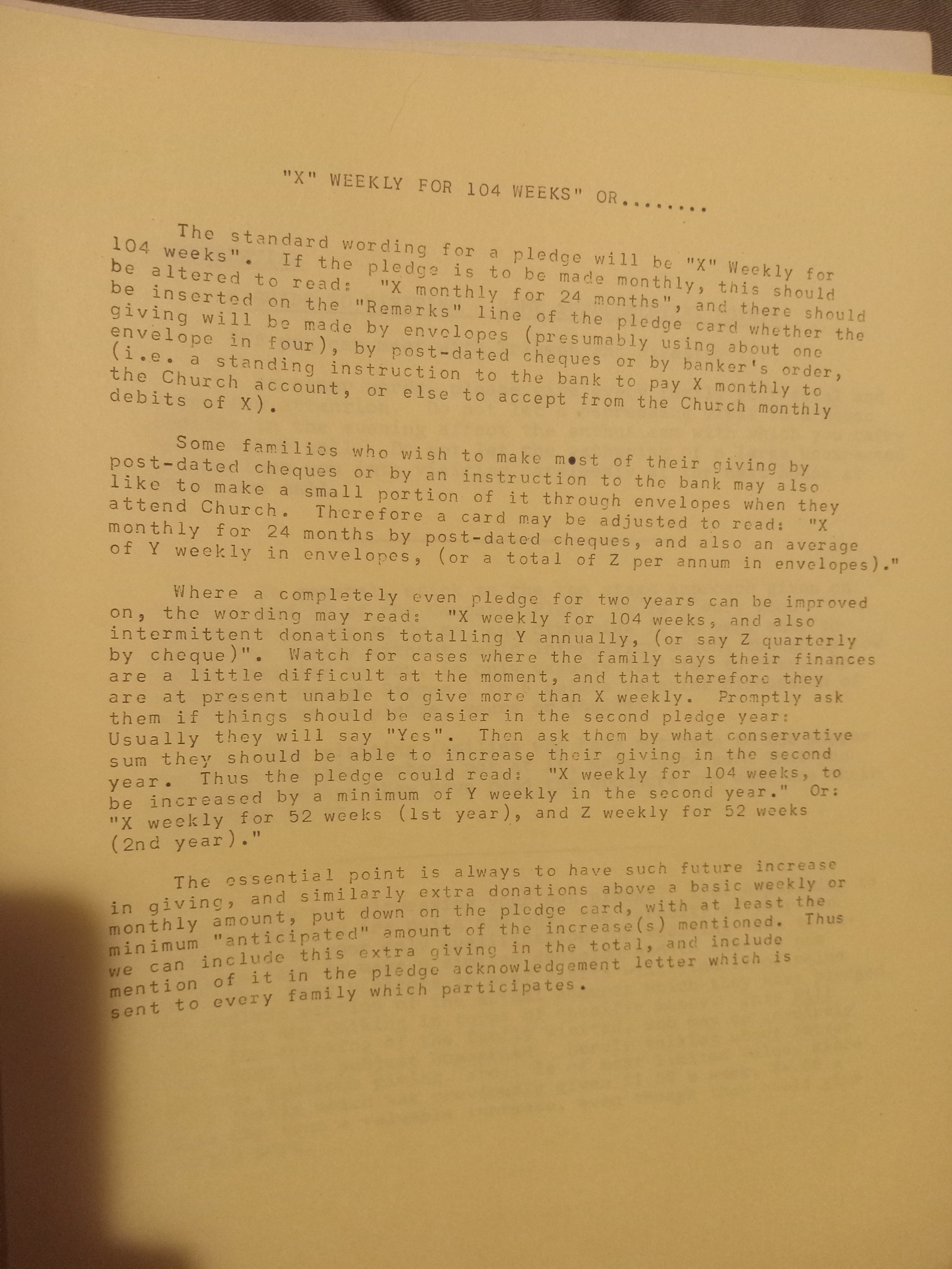

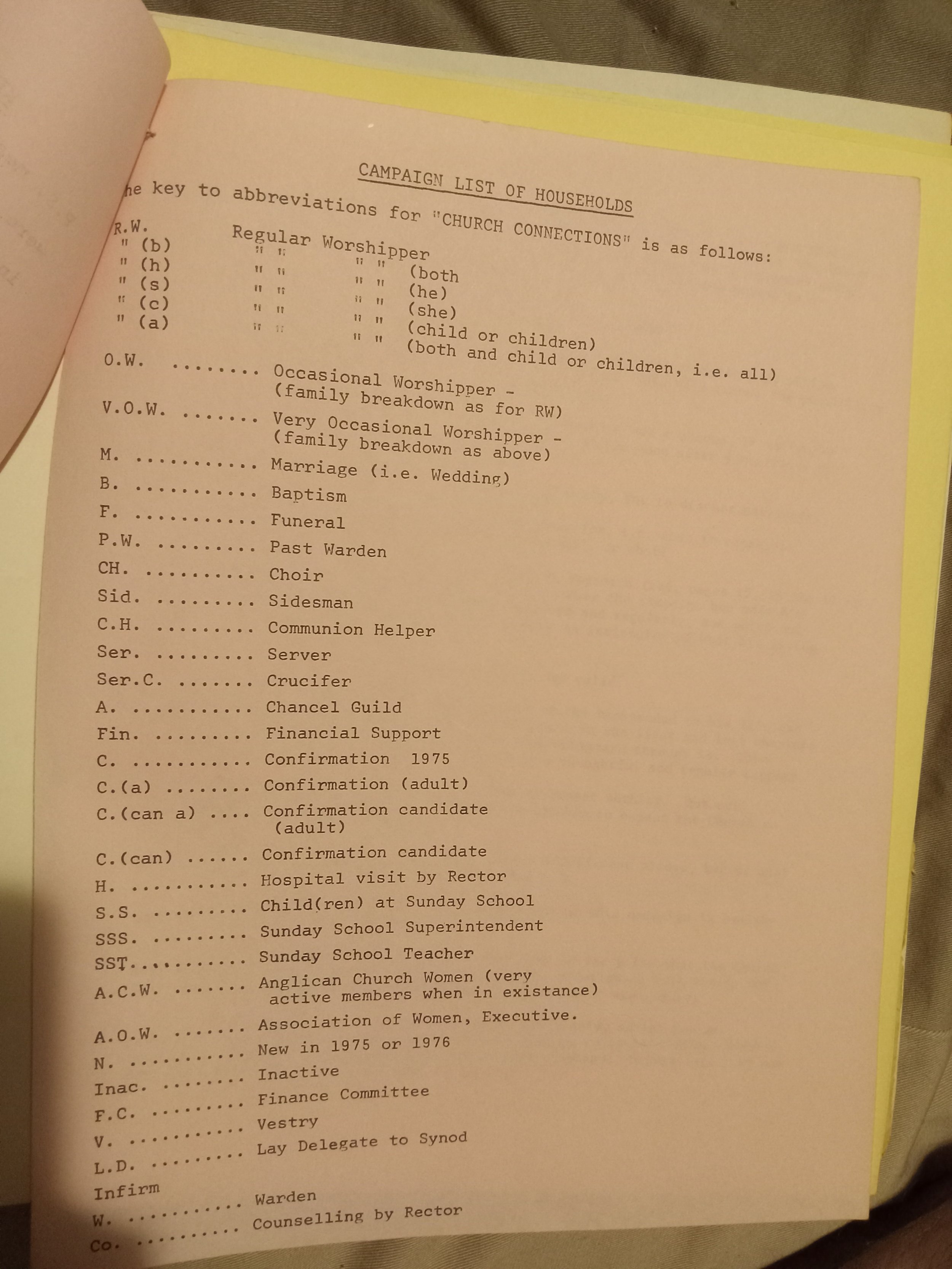

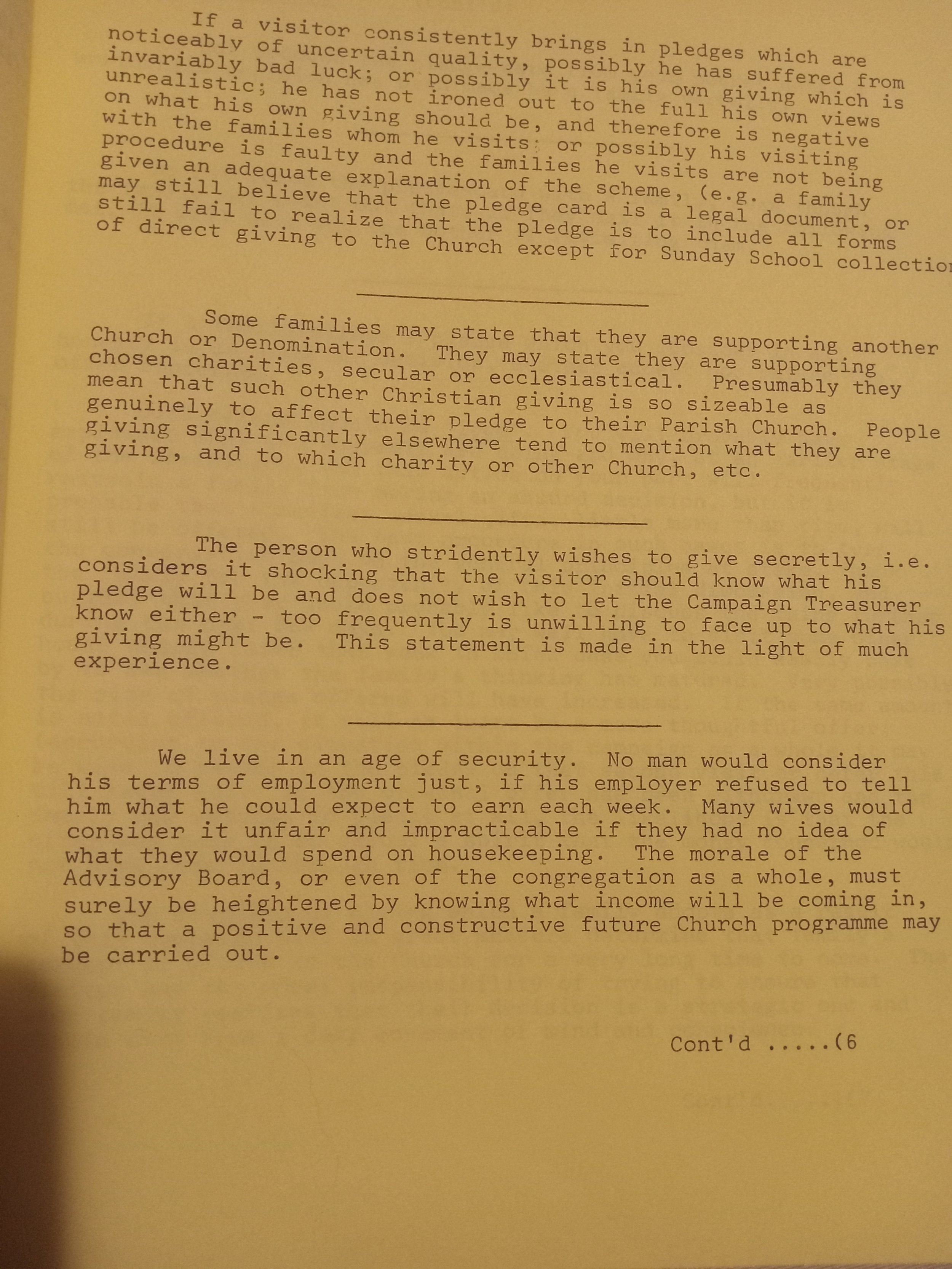

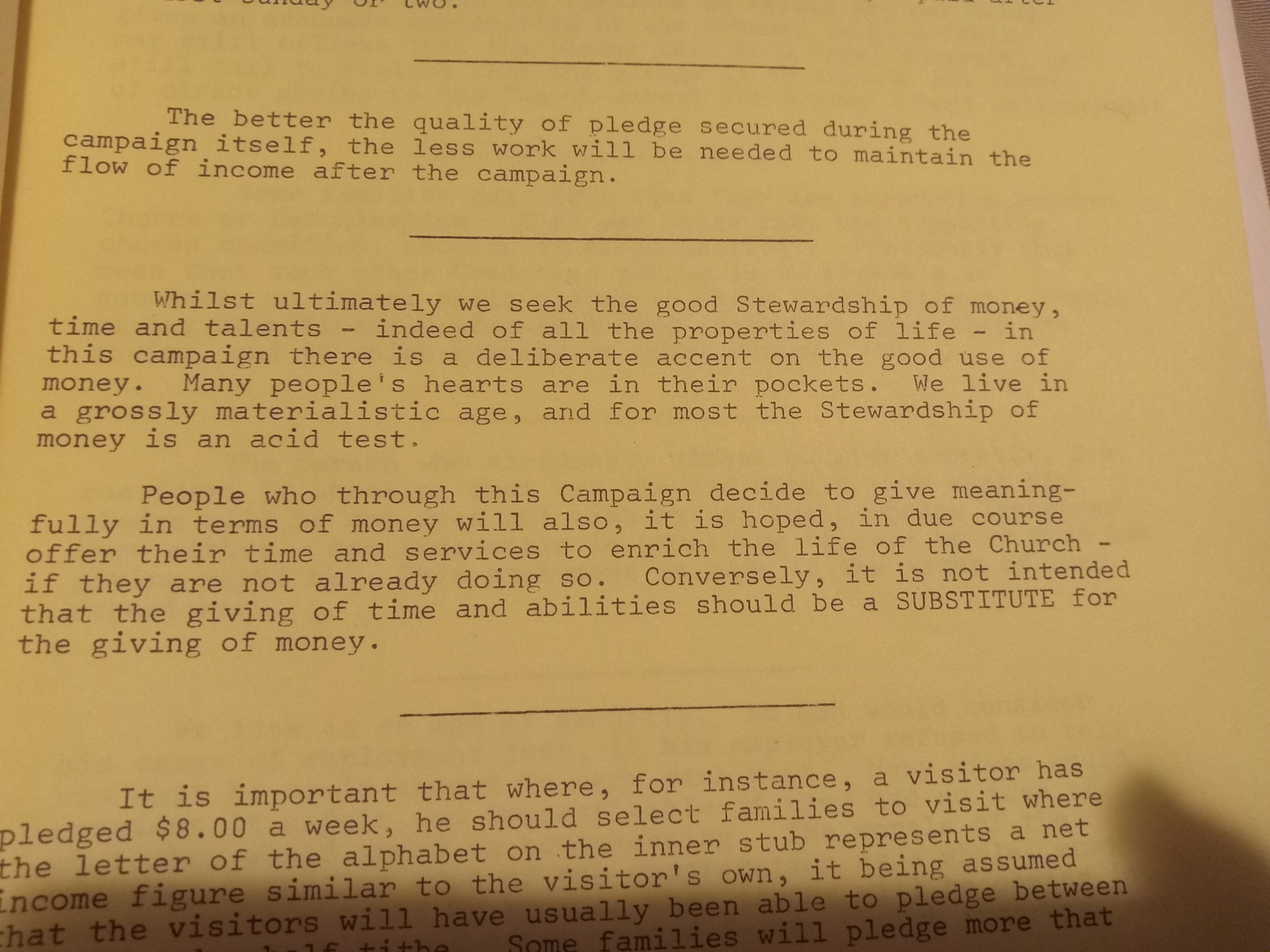

But the campaign itself is worthy of more attention, as it was a massive undertaking that involved many of the core “35/40 members” (and their families) and asked some difficult questions. New Horizons had a goal: pledge cards from each family on the parish rolls promising “X weekly for 104 weeks” – where X was, ideally, 5% of household income. Visitors, who had all already made pledges, were given a list of households corresponding to their own income bracket and were encouraged to use their own pledge as an example of what a realistic gift might be. They were also given a great deal of information about these families – whether they were a Regular, Occasional, of Very Occasional family; what connections they had to church organisations; whether members had been married, baptised, confirmed, or received a visit from the Rector; and, of course, approximate household income based on the occupations of the earning members. The 11-page guidebook includes many helpful hints to visitors, some of which were very practical – for instance, the insistence that post-dated cheques were the most reliable way for the church to receive money, or the repeated assertions that knowing what income to expect was a baseline requirement for security – and others of which might strike us as a little odd.

“Television,” visitors were warned, “can be a menace.” They were advised to ask families to turn down the television volume while receiving a visit. While visiting both husband and wife was encouraged, “sometimes it may be best to discuss the whole thing with the husband alone.” Secret gift-giving was discouraged, on the grounds that those “who stridently wishes to give secretly, i.e. considers it shocking that the visitor should know what his pledge will be” were likely a bit ashamed about how low their intended pledge would be in comparison to their income. The campaign’s focus on money, rather than including time and talents, was justified by saying that “for most the Stewardship of money is an acid test" of commitments to the church and a predictor for other kinds of contributions to the church life – the latter of which should not be “a SUBSTITUTE for the giving of money.” Visitors were encouraged to be firm and dogged, true salespeople of these pledge cards, and to not hesitate to point out some basic hypocrisies. One of these was that it is entirely unfair to not give to the church your whole life, but to expect it to still be standing when the time comes for you to be buried – why should others keep the church open on your behalf, so that it can receive your body?

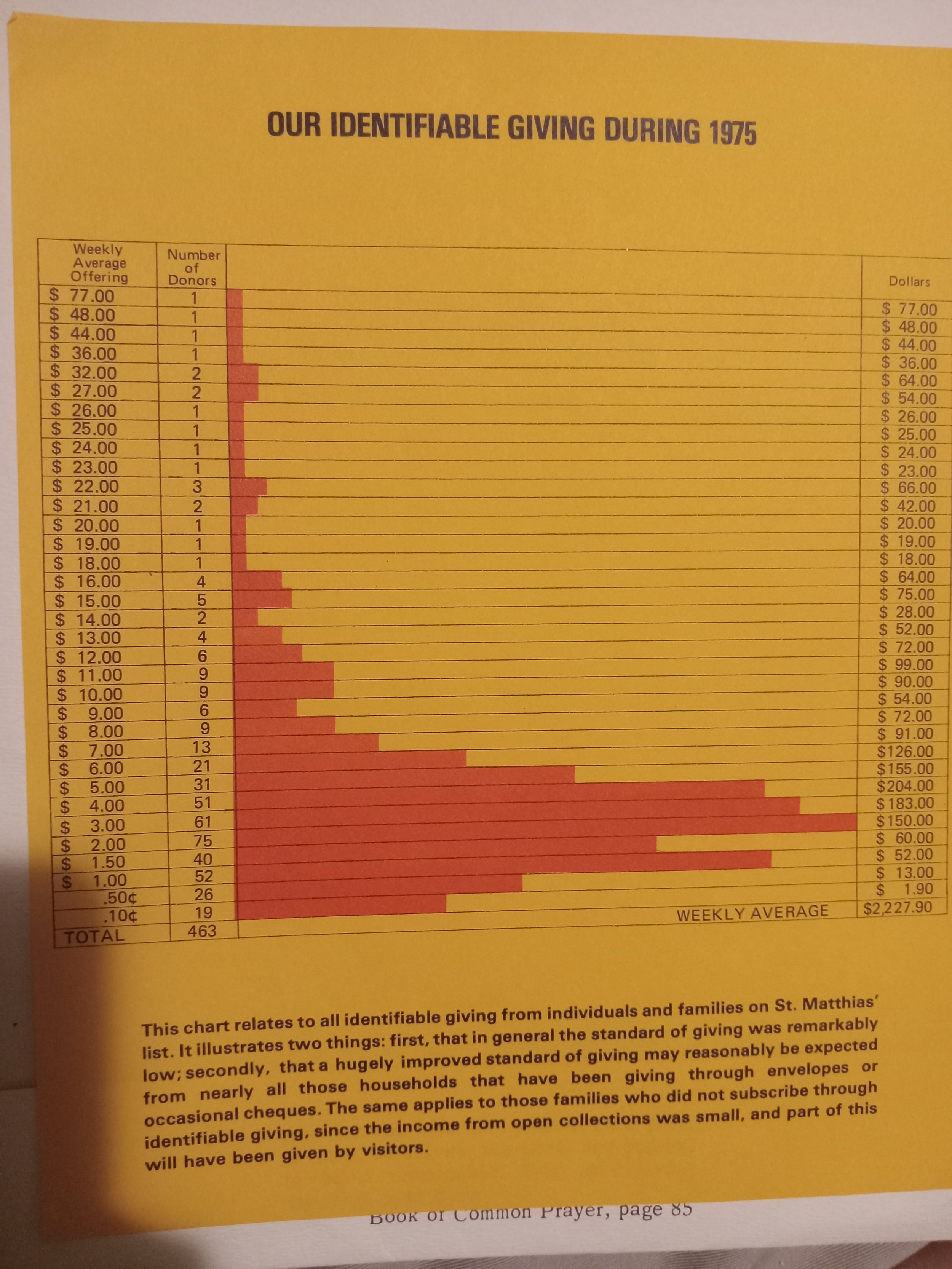

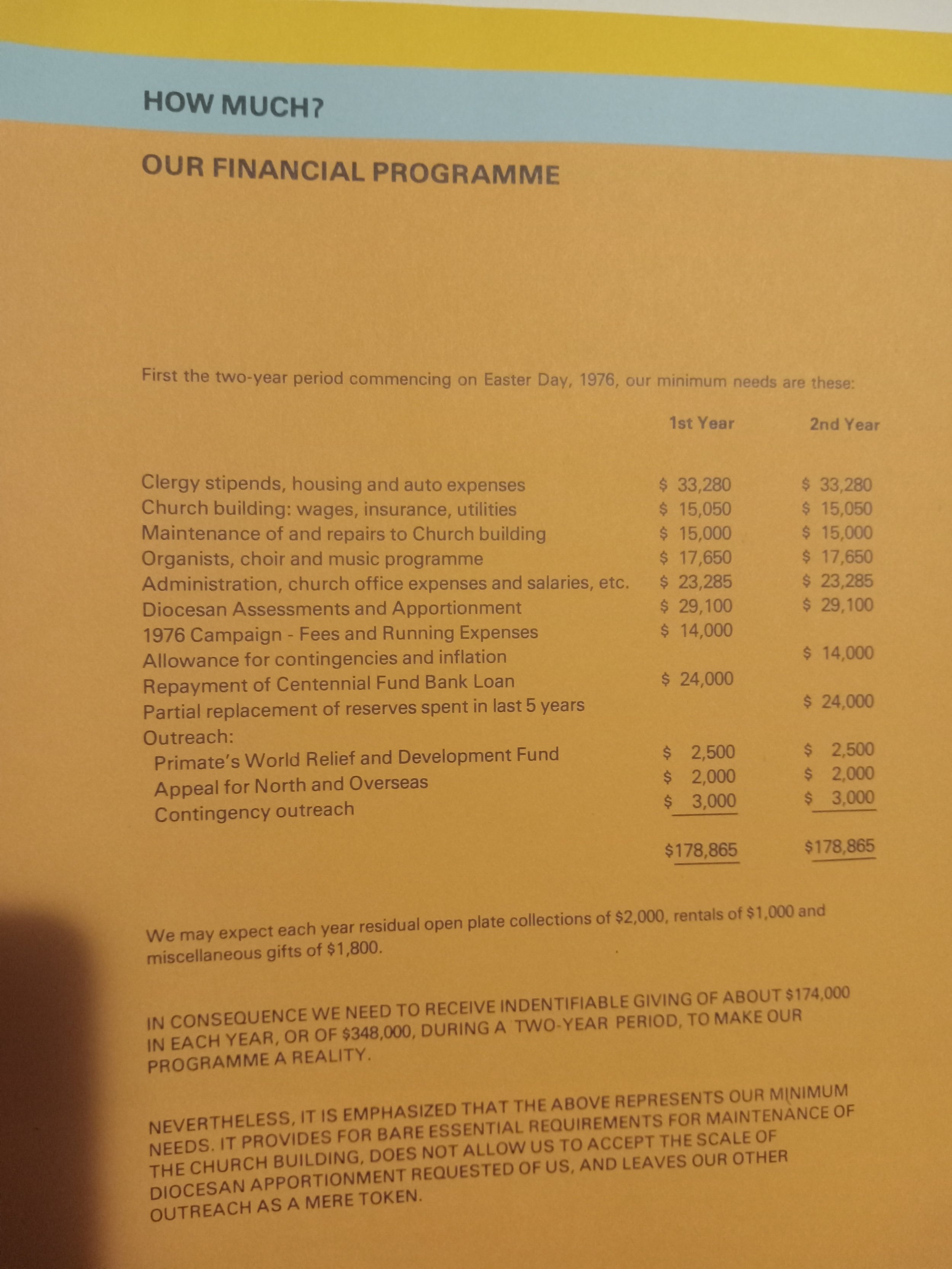

The campaign was not all about hard truths, however; its other pillar was information about the actual costs of running the church and its many parts. Much like St. Matthias’ is doing now in compiling narrative budgets, the New Horizons campaign listed the daily usage of the buildings, the tasks of the clergy, the minimum financial needs for the next two years (about $179,000 yearly; $907,000 today), and the principle of REGULAR, THOUGHTFUL, and DEFINITE giving. Even more striking than the letters from the Bishop and the Rector accompanying these documents is the breakdown of weekly giving by identifiable givers, which shows weekly giving ranging from $77 (today: $390; 1 donor) to $0.10 (today: $0.51; 19 donors), with the bulk concentrated between $1 and $6 weekly (today: $5-$30; 331 of 463 donors).

Despite the massive effort that went into the New Horizons campaign, the finances did not markedly improve, and just ten years later, in 1986, Vestry adopted the policy of offsetting the annual deficit, which had existed every year of that decade except for 1984, with withdrawals from the memorial fund. This would remain the standard operating procedure into the 2010s. The following year, Rev. Paul James told the parish in his report to Vestry that the budget looked healthier – thanks to some drastic cutting of expenses – and that, ultimately, “when our Ministry is right our finances will be so as well. And in that order.” He recommended an increased focus on outreach and community care.

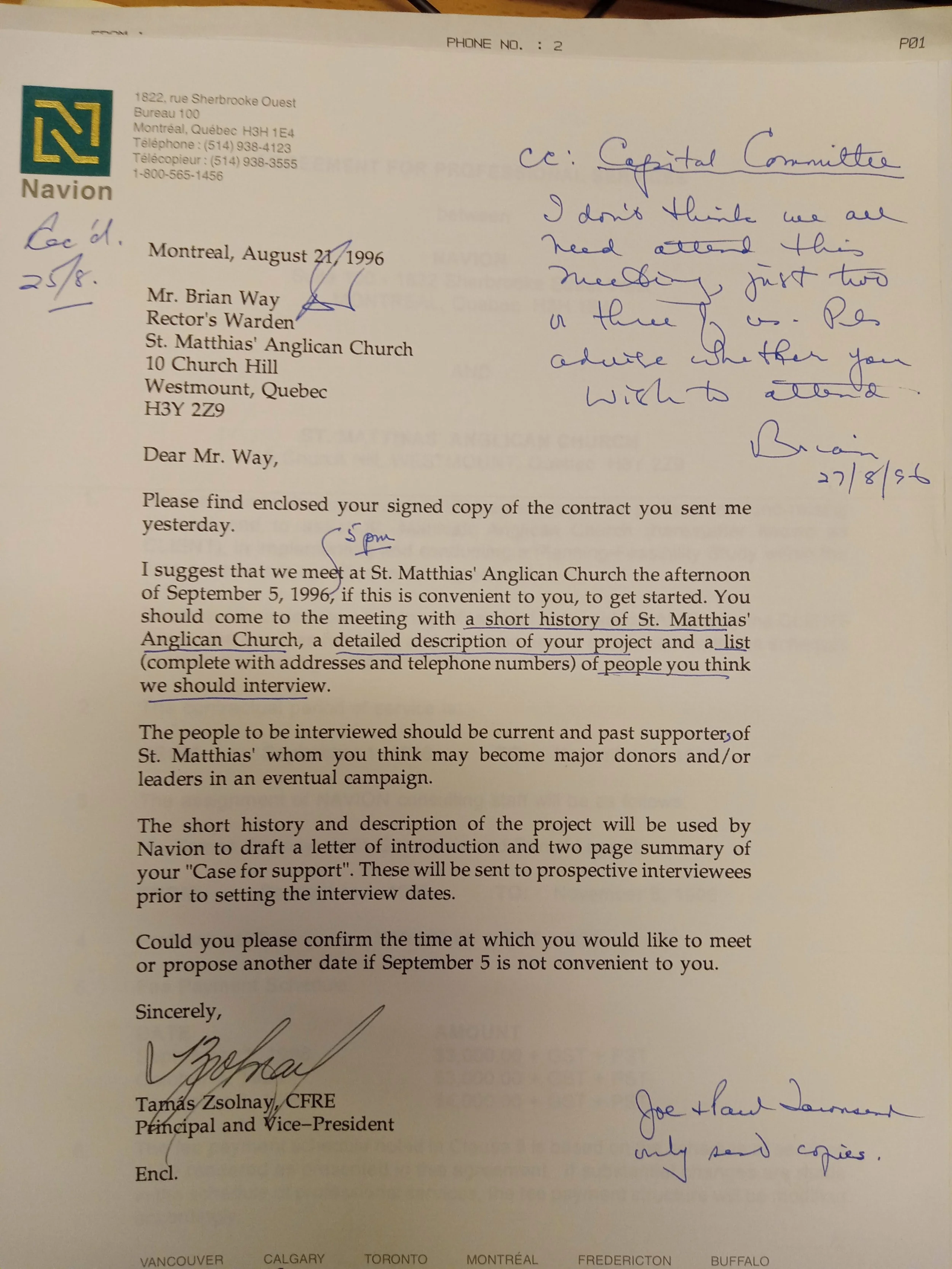

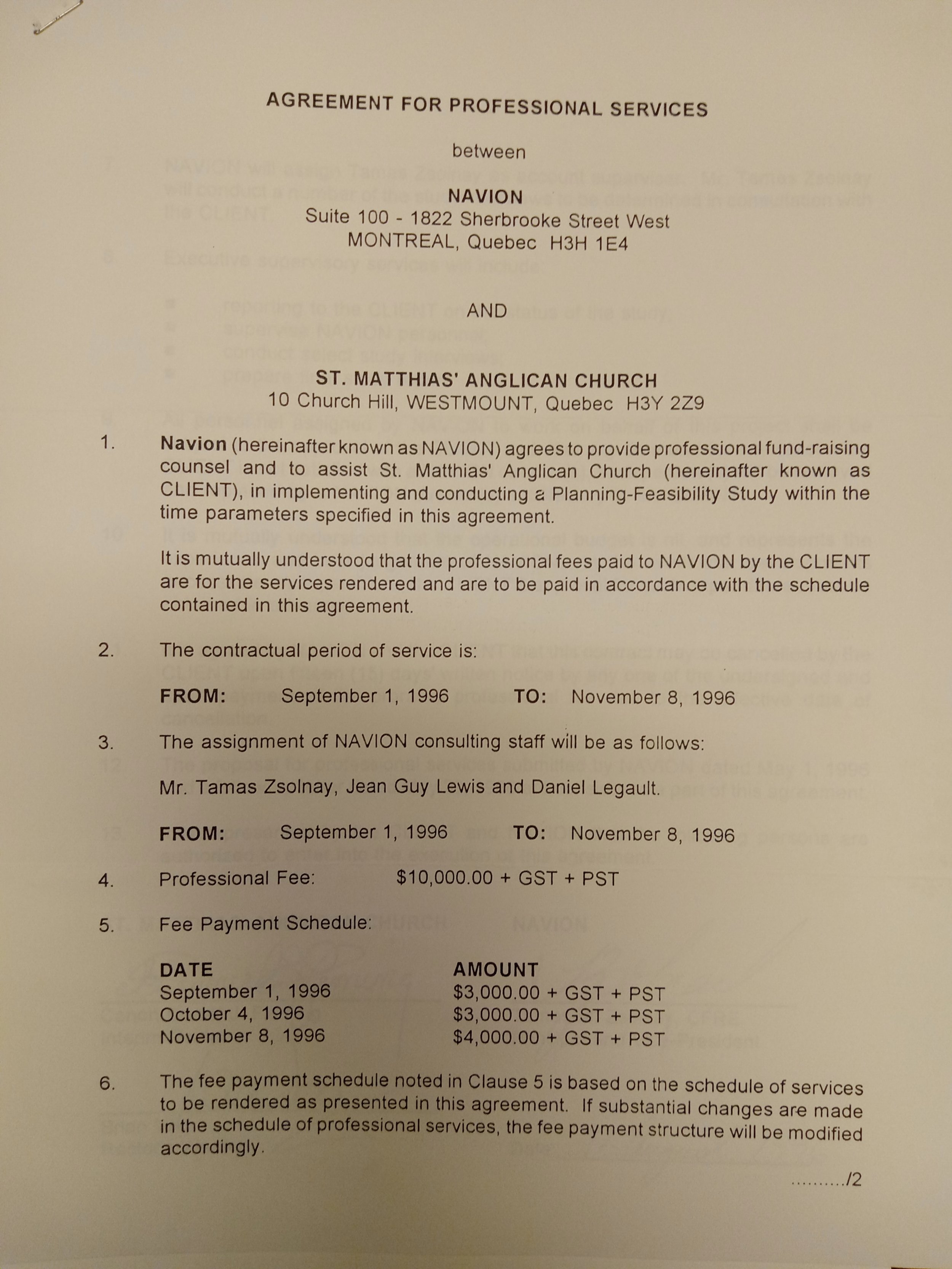

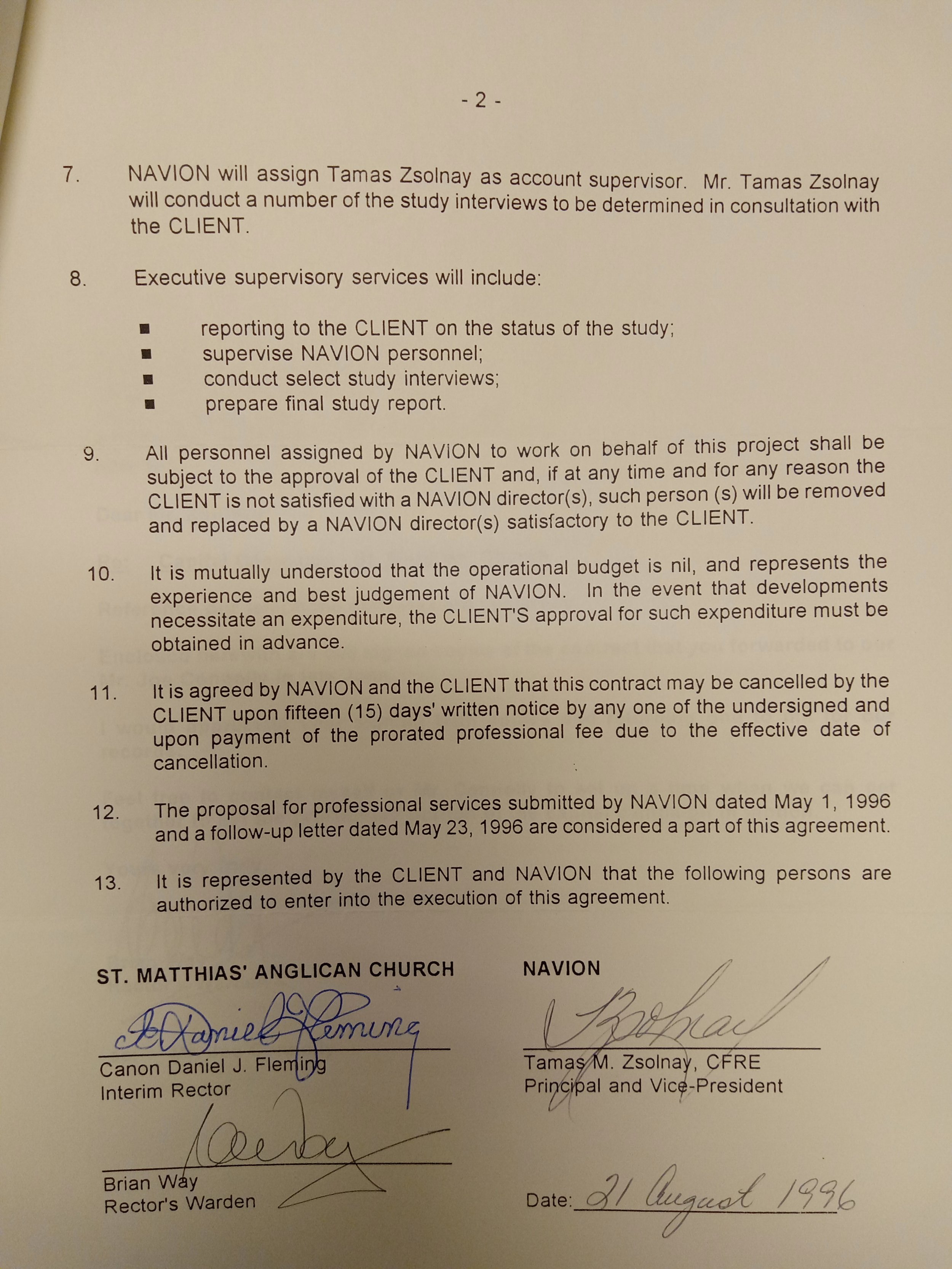

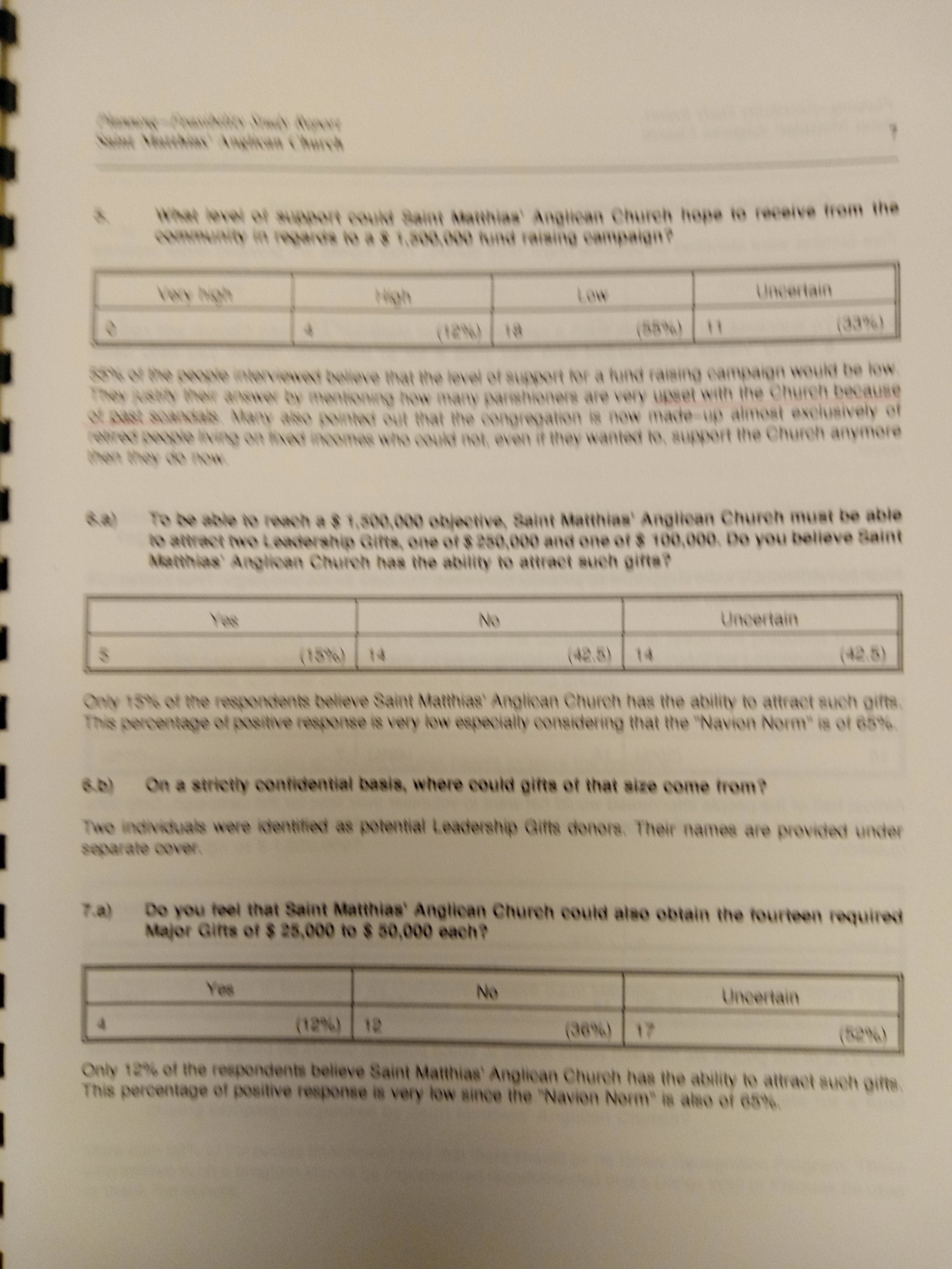

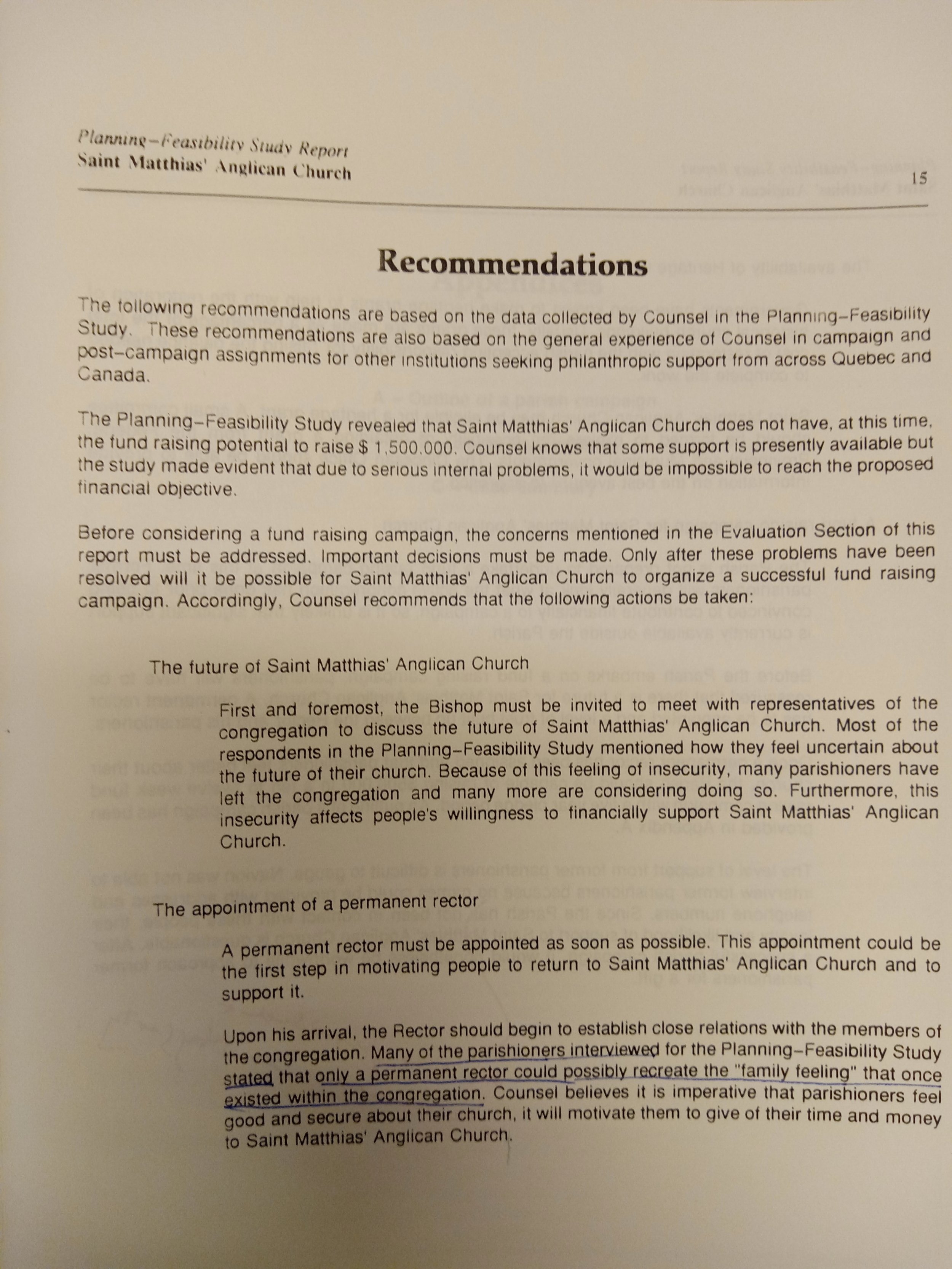

In the 1990s, yet another major fundraising operation was envisioned, with the help of a firm called Navion. Navion conducted a feasibility study for a fundraising campaign through 1996, and a second in 1998, surveying the congregation on their willingness to volunteer to help with the kind of solicitation of donations that had been accomplished in previous campaigns. The results of the reports are grim – there clearly was not a will in the parish to perform the same kind of visiting and soliciting money. Navion ultimately concluded, in 1996, that St. Matthias’ did not have the potential to raise the kind of money it needed to, but that perhaps, with the appointment of a permanent rector, the situation would change. Rev. William Blizzard was indeed appointed in 1997, but the 1998 report is not any more optimistic about the possibility of fundraising success. Nevertheless, by the time Rev. Ken Near left in 2014, he was optimistic about the state of the parish finances. Pledge cards were back, giving had increased, and Matthians “now contribute the most of any parish in the Diocese.” This success was, however, based largely on the continuation of prominent – and aging – givers, and Rev. Near’s letter expresses the concern that the finances might again be in turmoil as givers pass away. The portions of the letter not included in this post include a breakdown of possible estate giving in quite clear detail, indicating that although parish visits had stopped, the church was continuing to use their knowledge of the personal finances of parishioners to tailor their fundraising.

This weekend, St. Matthias’ is hosting a “Stewardship Sunday” in which we celebrate all of the many contributions that keep our community together as a community. Talking about money seems harder in 2023 than it did in 1873, but it is clear that although many of the past 150 years have been spent in financial struggle, we have come together to weather each and every storm – whether they were of our own ambitious-project making or not!