November 4th: The Organs

St. Matthias’ was officially founded as a mission of St. George’s, Place du Canada, in 1873, which means our community is 150 this year! For the next 12 months, we’ll be diving into the archives to shine the spotlight on particularly interesting parts of our history.

Exactly 50 years ago today, St. Matthias’ welcomed the newest – and largest – member of its pastoral team: a gorgeous tracker organ built by German organ-maker Karl Wilhelm and voiced by medieval wind instrument specialist Christoph Linde. The organ was a major investment, and it was worth every penny: fifty years later, it has needed only minimal maintenance, and the musical leadership it provides continues to place it among the best organs in the province. But it was not the first organ to lead Matthians in worship – indeed, in the preceding 85 years, the church had been through at least two organs.

Organ 1 & 2, or 1 & 1.5

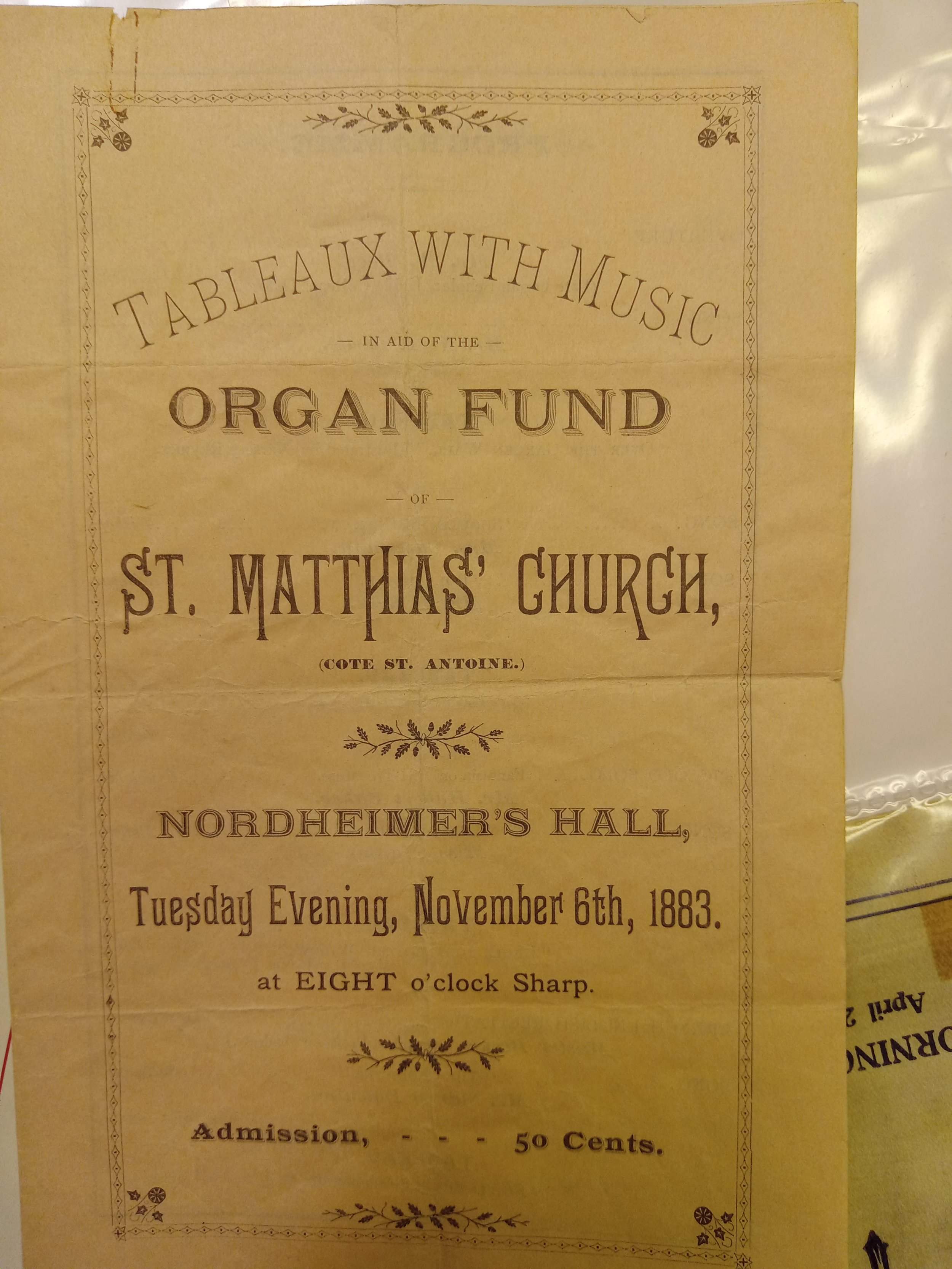

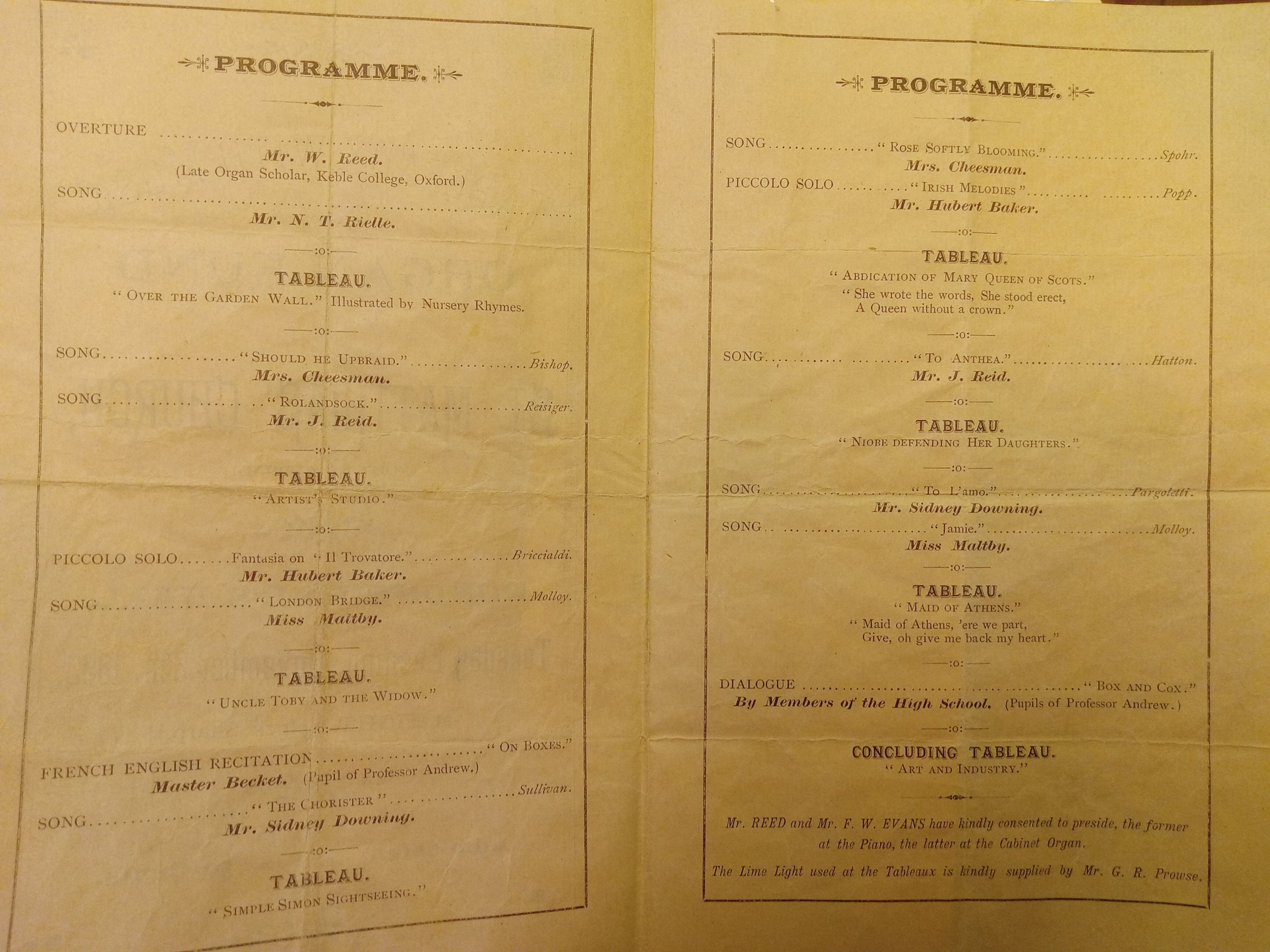

We don’t know much about this organ, aside from the fact that it was very quickly replaced in whole or in part. In 1883, St. Matthias’ as a congregation was only ten years old, and it had been inhabiting its original building (link to relevant blog post) for a mere seven years. But seven years of multiple services each week is a long time to go without the kind of musical accompaniment that has been standard in churches since very early in Christian history! Matthians of the 1880s were no strangers to fundraising, having secured the funds to raise their first building so recently, and the elegant appropriateness of this particular fundraiser shows that, already at this early stage, they were an artistic bunch, too. The hall in which this 1883 fundraiser was held, in what we now call Old Montreal, had been built in 1849 by Toronto-born brothers Abraham and Samuel Nordheimer, piano-sellers. The concert hall that abutted their showroom and offices would be destroyed by a fire in 1886, but the Nordheimers would rebuild it in 1888, and the new hall would go on to welcome one of Montreal’s first symphony orchestras, Emma Lajeunesse, and Sarah Bernhardt.

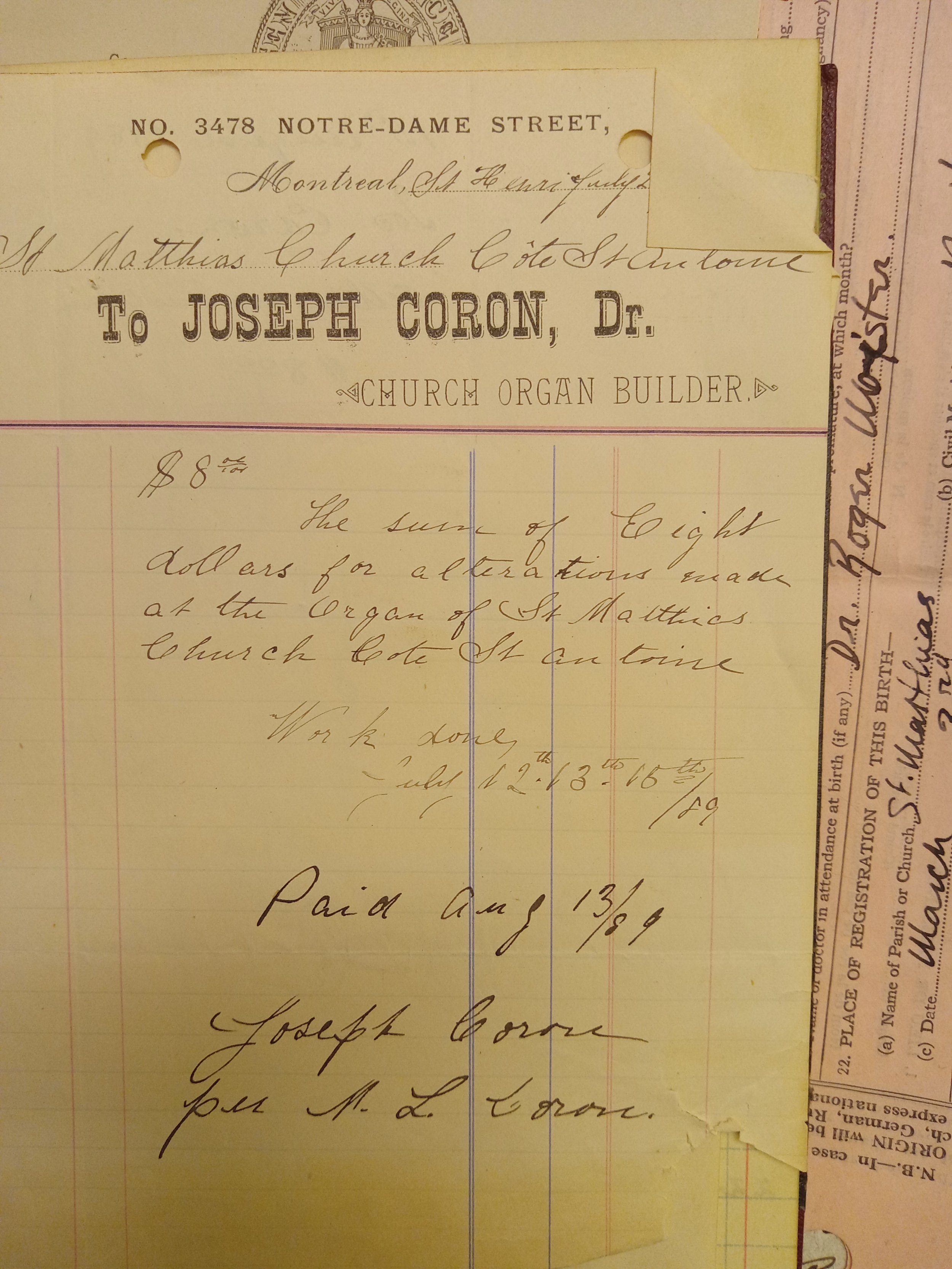

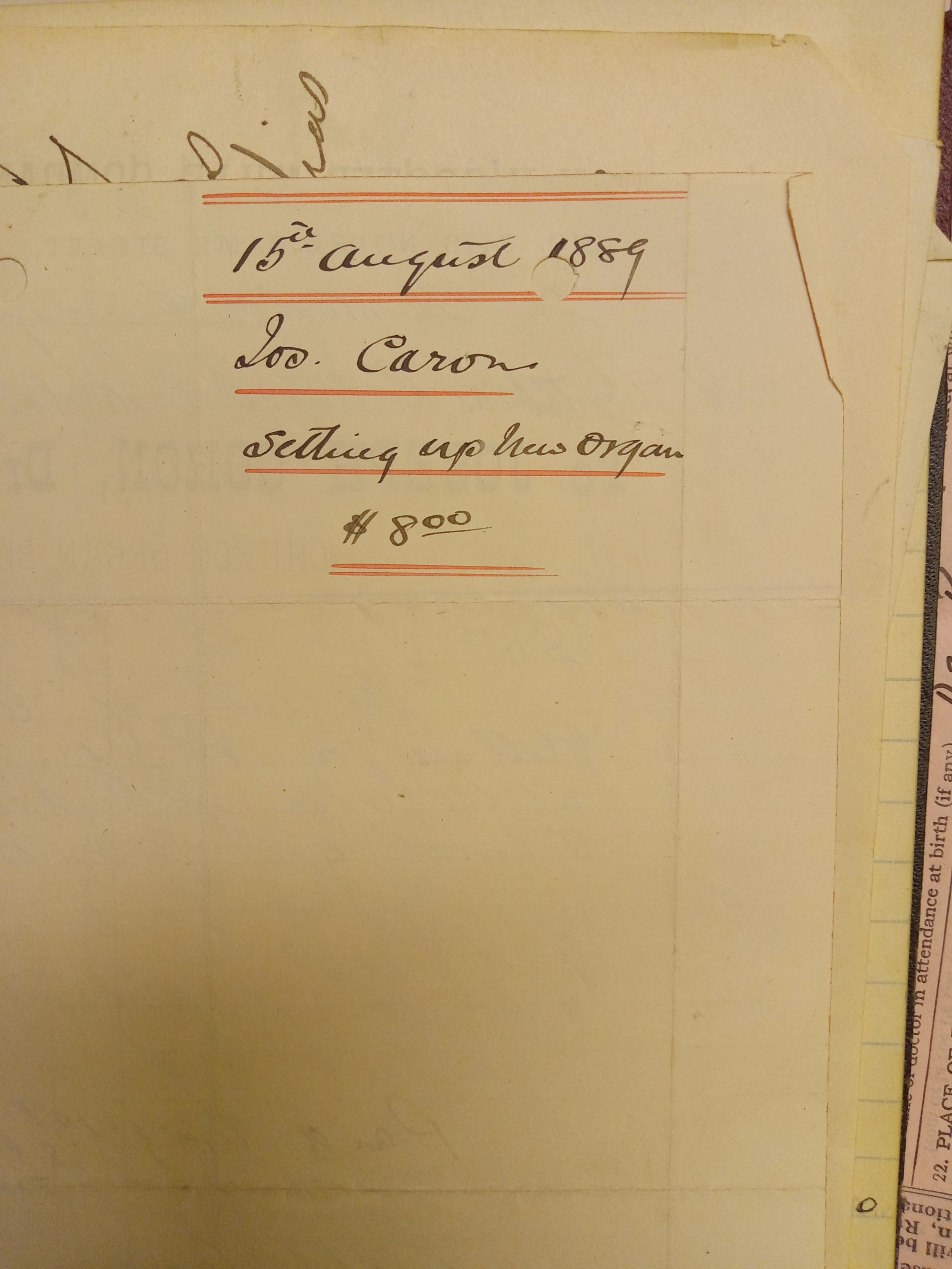

We do not have record of the organ being built, or of how much was raised at this fundraiser, but in 1889 one Joseph Coron, Dr. and Church Organ Builder, charged St. Matthias’ for “alterations made.”

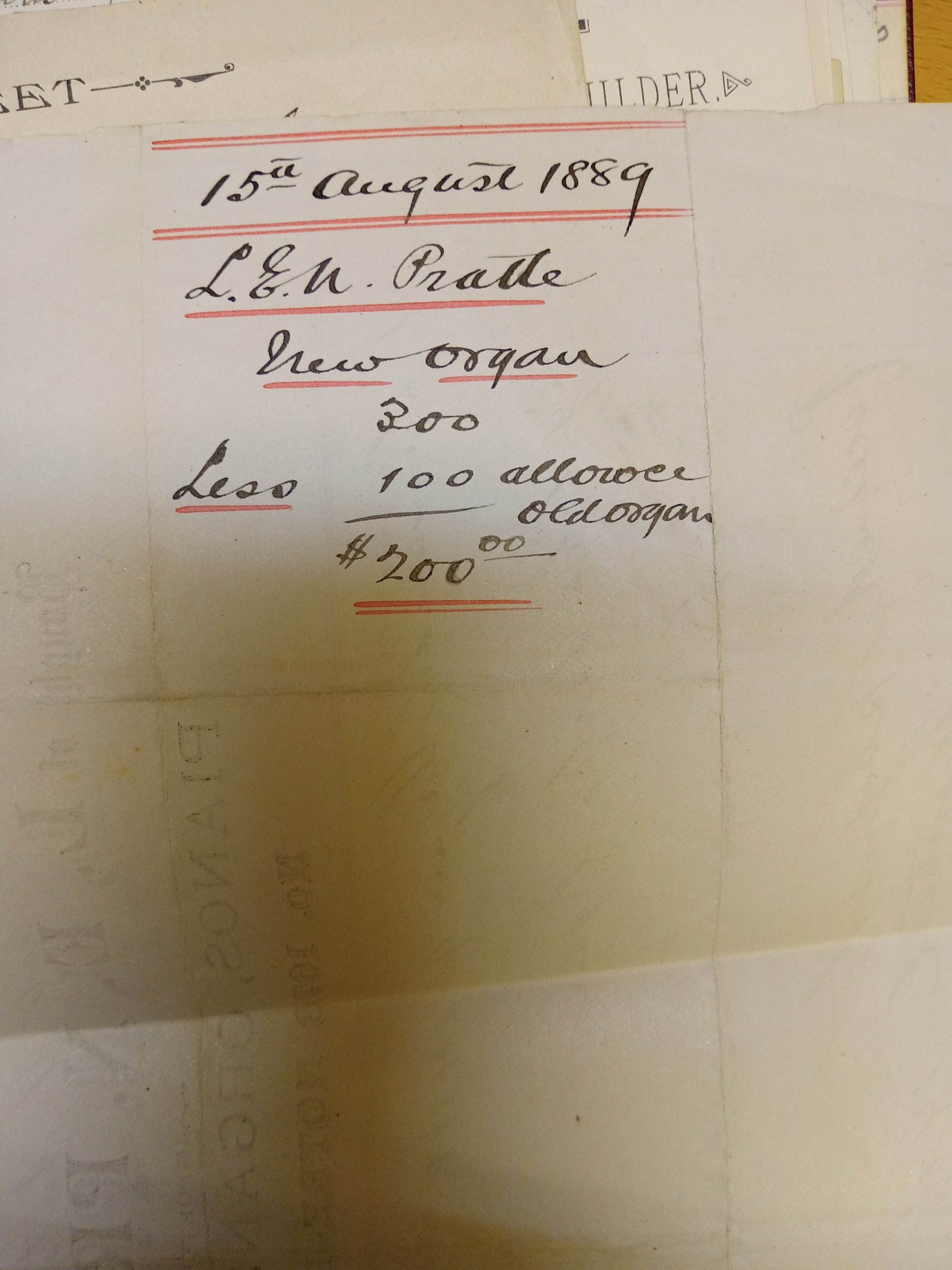

Taken together, we might assume that between 1883 and 1889, an organ was installed, and like all instruments it needed a bit of maintenance – except that, on the reverse of Dr. Coron’s bill, the treasurer has annotated that this charge was for “setting up new organ.” A bill for the exact same date for L.E.N. Pratte, “importer of pianos, organs and harps” is also attributed to the “new organ.”

What are we to make of this clear difference? Surely the setting up of a new organ and the alteration of an old one are different operations. It is possible that the treasurer, not being a music man, made a mistake, but it is also possible – and your humble historian believes it is more likely – that the 1889 organ was both new and an alteration. St. Matthias’ current organist, Scott Bradford, who has proved an excellent interpreter of these historical documents, says that new organs were not necessarily built from the ground up. Often, they were cobbled together from existing organ parts, resulting in a more affordable final product. Although St. Matthias’ has always lived beyond its means, it is possible that the 1889 organ was new – to St. Matthias’ – by way of parts being added to the 1883 organ, which Dr. Coron might very well call “alteration.” Indeed, L.E.N. Pratte struck $100 off their bill for the new instrument as an “allowance” for the “old organ.”

Dr. Coron’s own identity is difficult to uncover, but he may have been related to one of the first organists in Quebec, Charles-François Coron, who was active in the 1720s and 1730s in the parish church of Notre Dame. As for Louis-Étienne-Napoléon Pratte, he had been importing pianos since 1875 to his shop on Notre-Dame, and 1889 marked the beginning of his foray into building instruments in-house.

Organ 2, or perhaps Organ 3

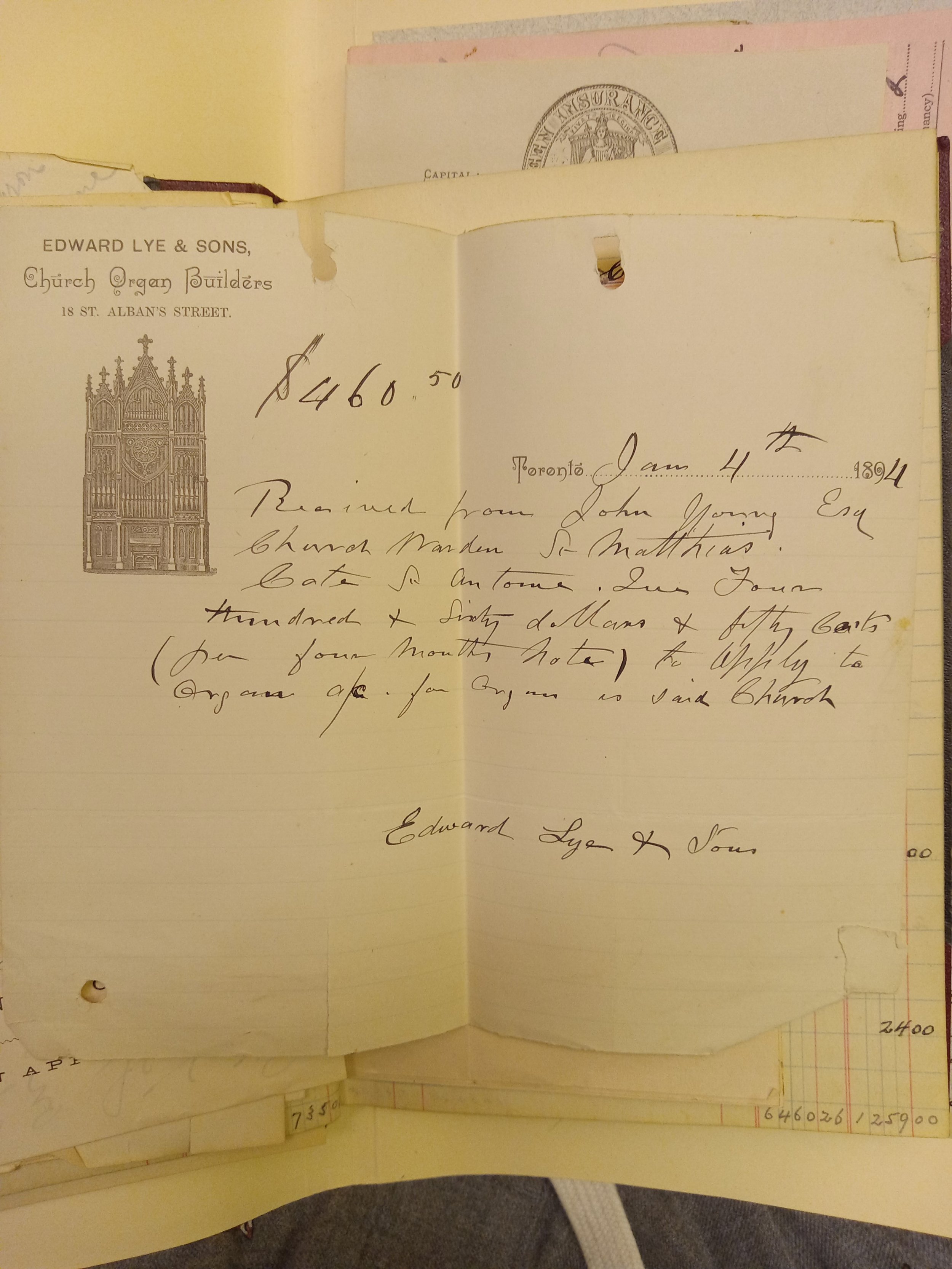

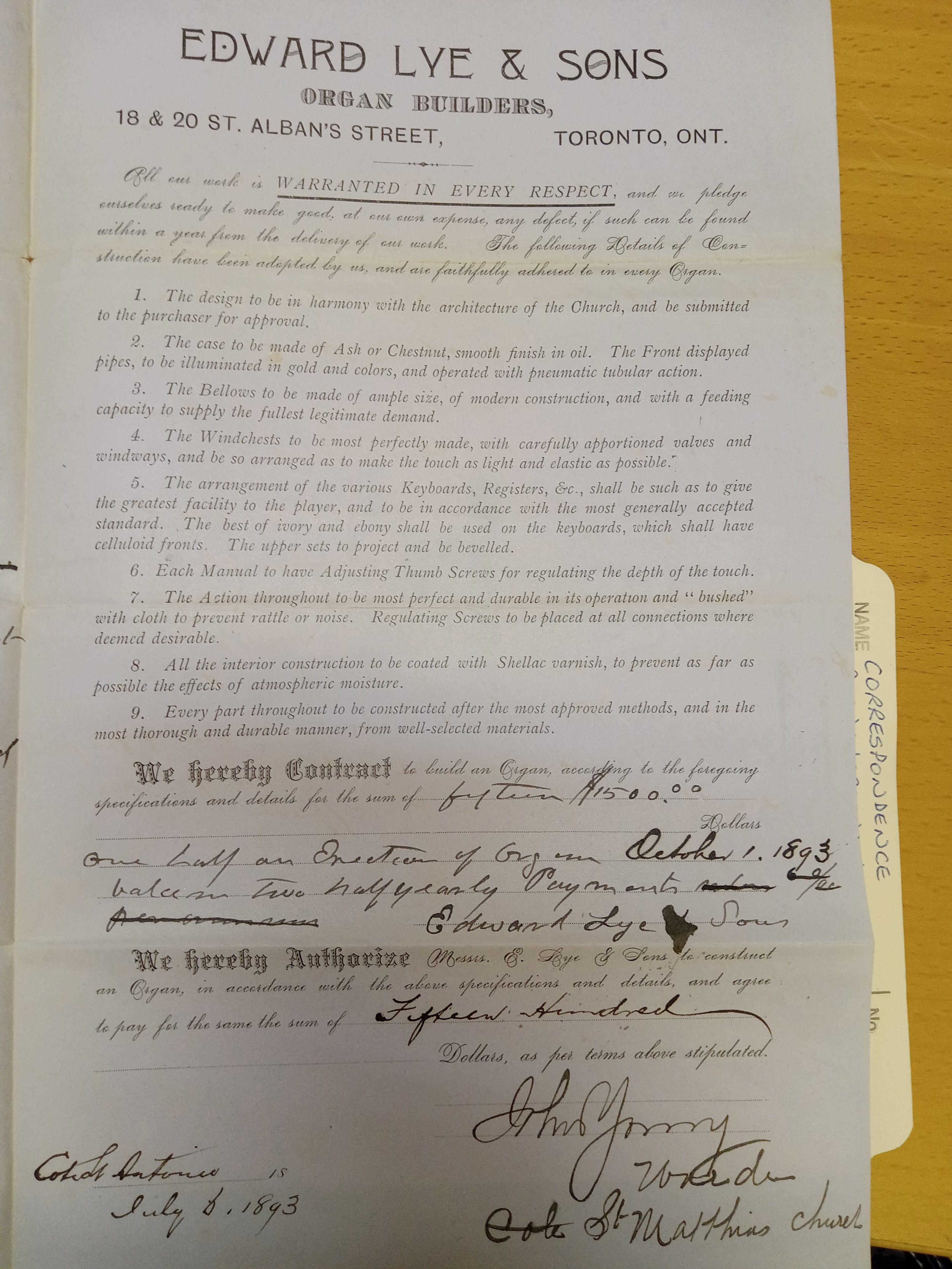

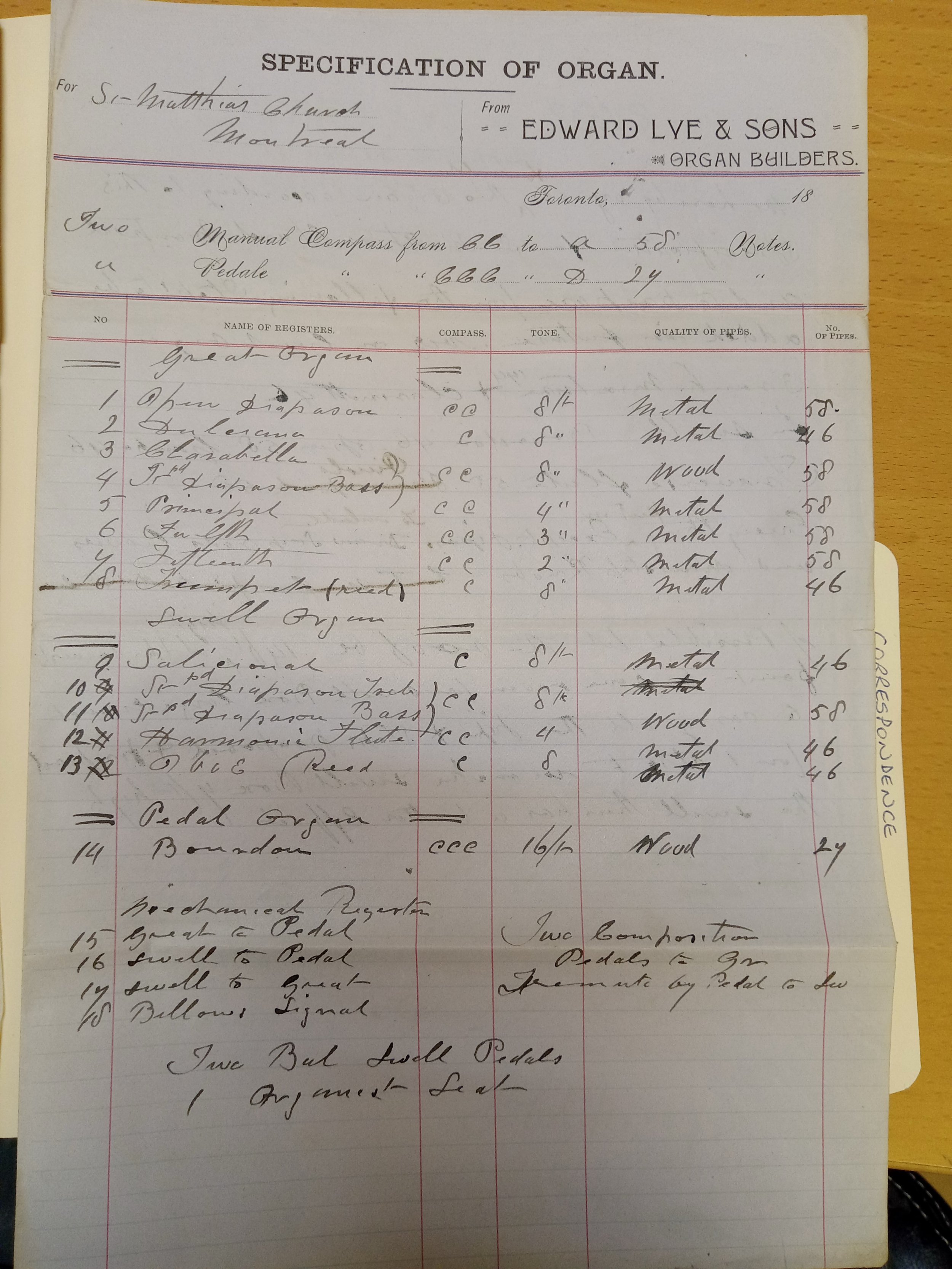

This organ again needed attention in 1893-4, this time from Edward Lye & Sons, Toronto-based organ builders that would continue to be active until 1982. Unlike Dr. Coron, they are easy to find, in large part because in Toronto alone they built at least 60 organs between 1881 and 1948, and their instruments appear throughout Ontario and sporadically in other provinces, many still in use.

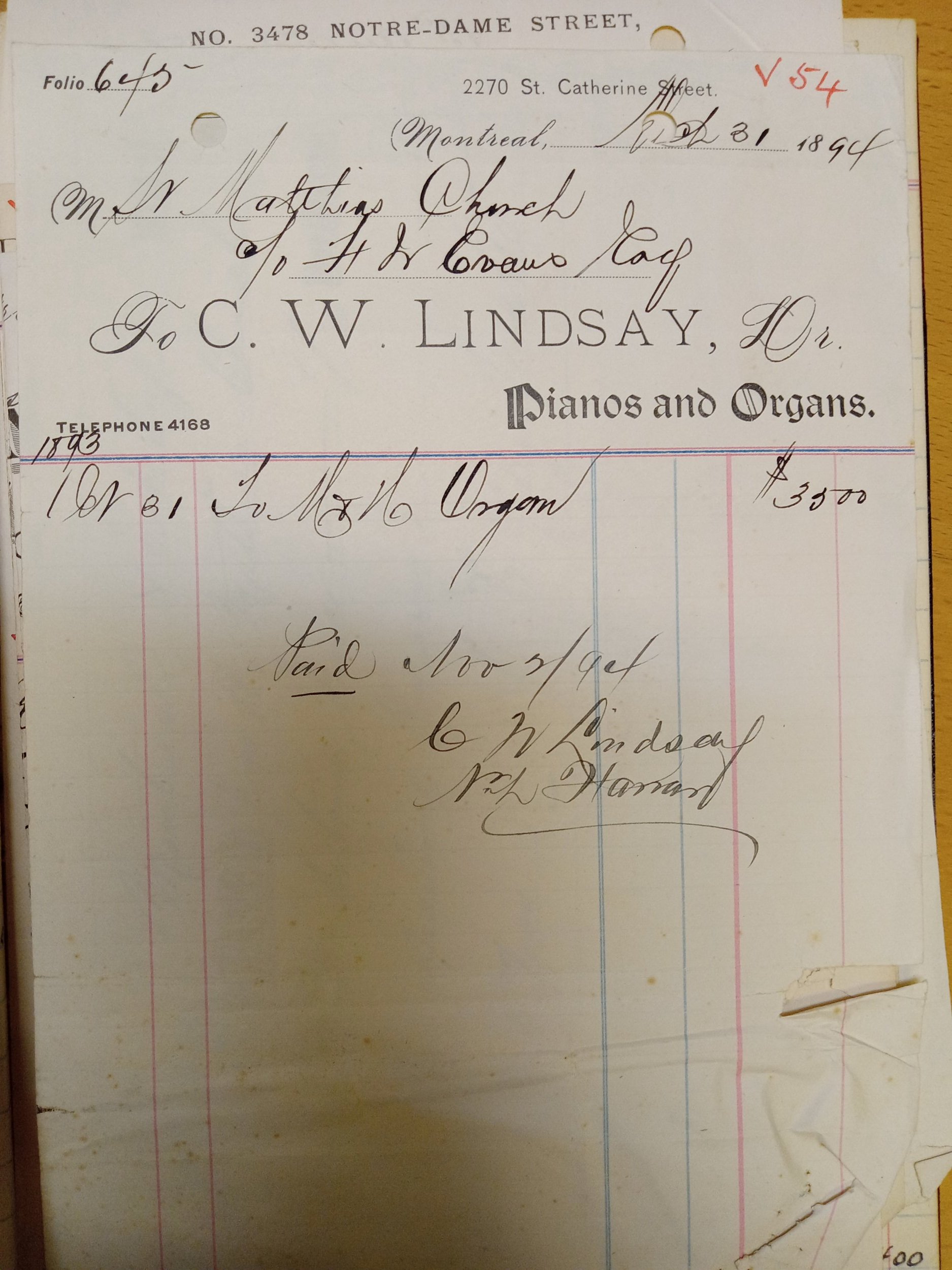

In 1893, they contracted to build quite a significant organ for the church - we have no record of whether the contract was in fact carried out, but as one rarely contracts to build things one does not intend to actually build, we can call this yet another organ! In 1894, climate control for the organ was the main expense; organs, it turns out, are very temperamental about humidity. Also in 1894, Dr. C.W. Lindsay, who would go on to buy Nordheimer Music Hall in 1897 but who was at the time merely a Boston-trained piano and organ maintenance technician - who had the additional distinguishing feature of being blind - did unspecified maintenance work on the new instrument.

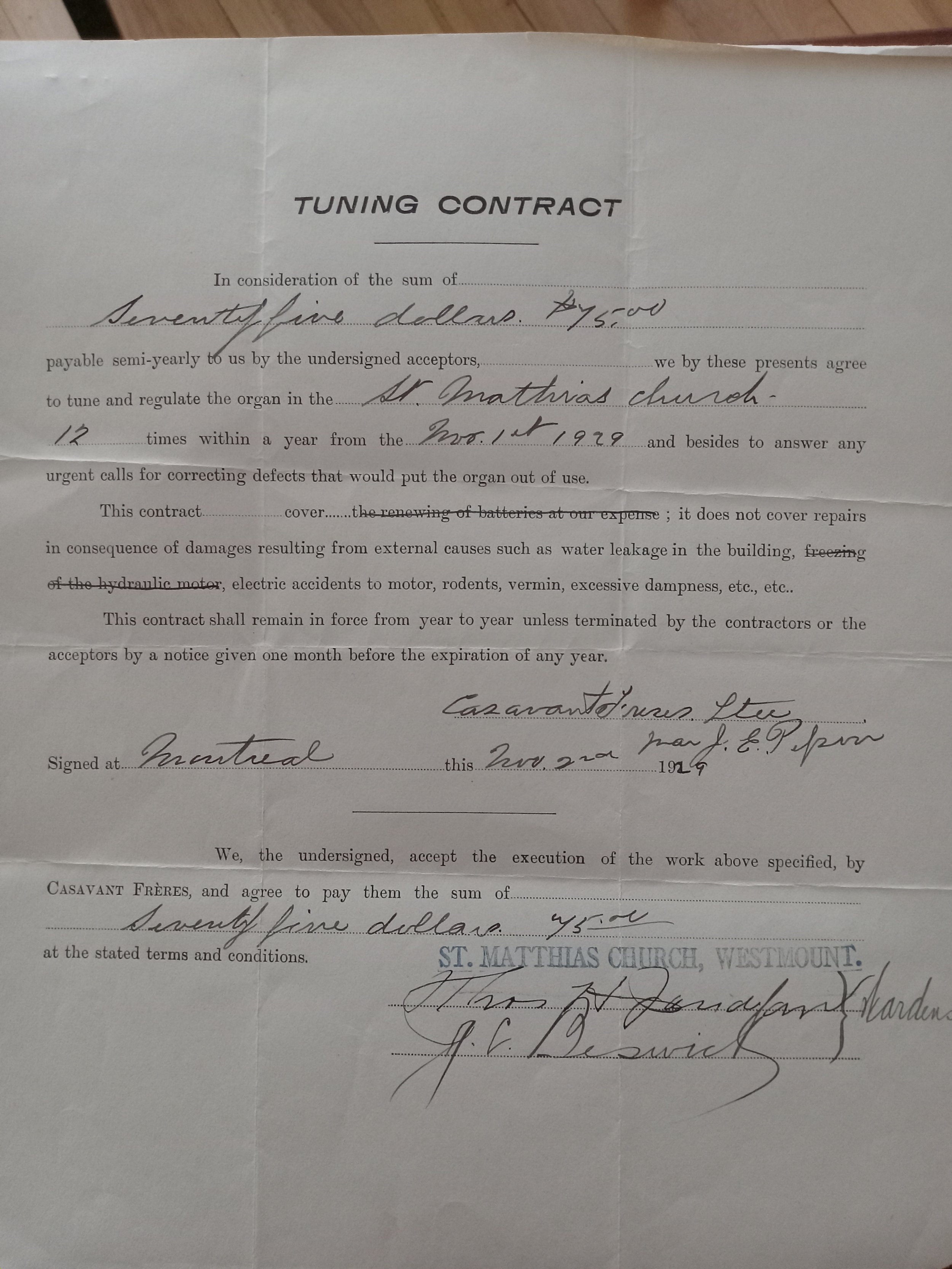

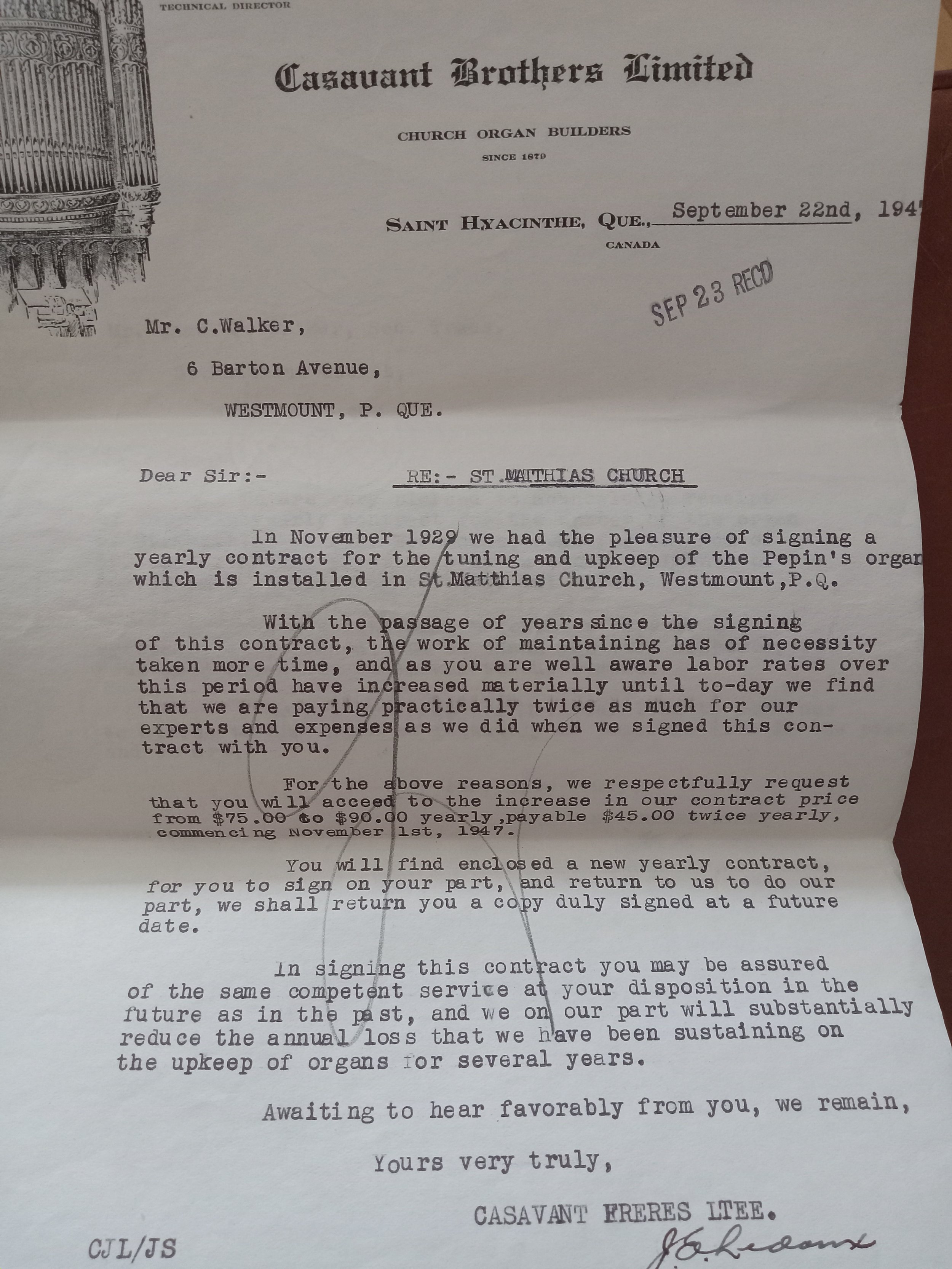

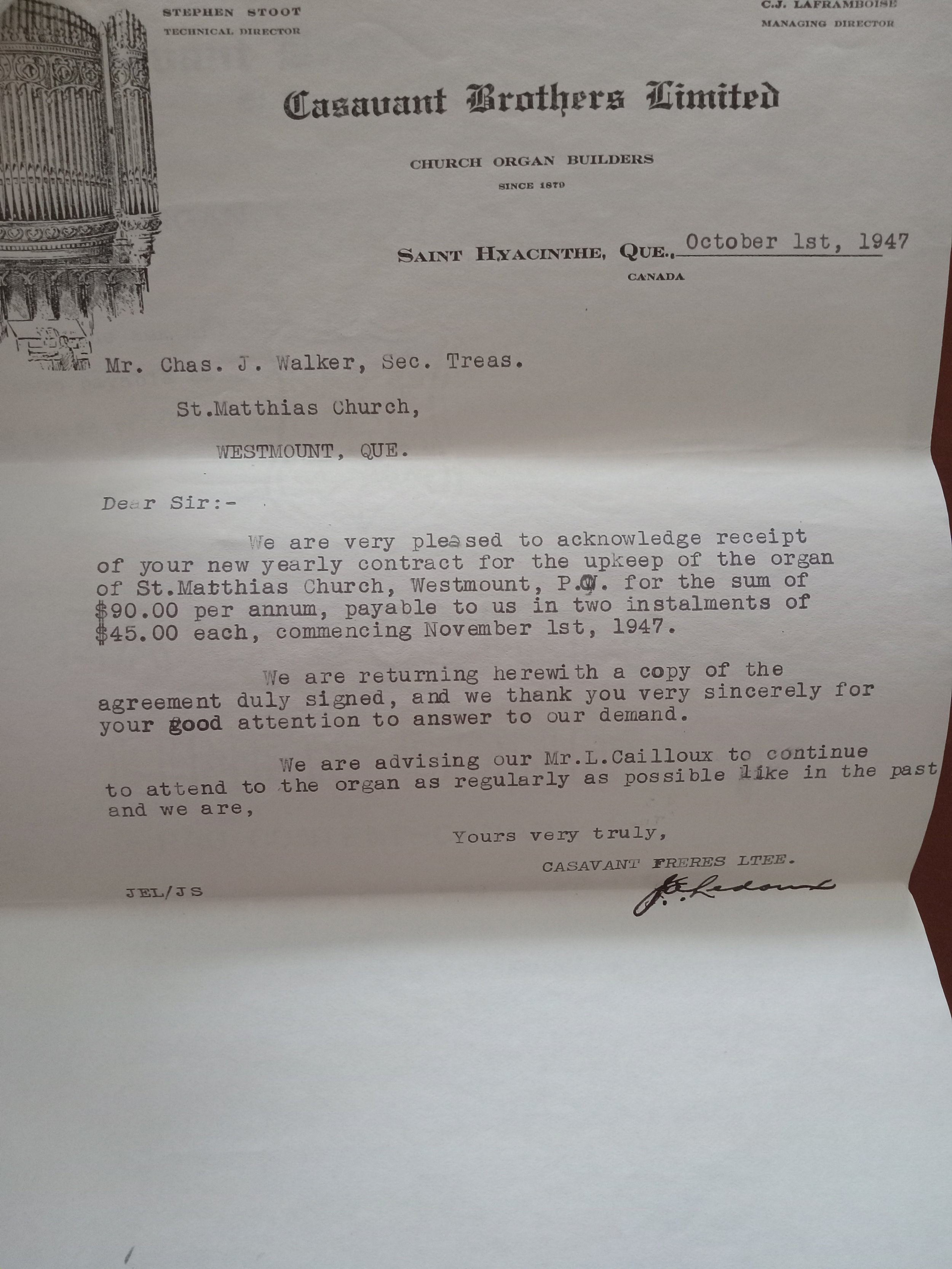

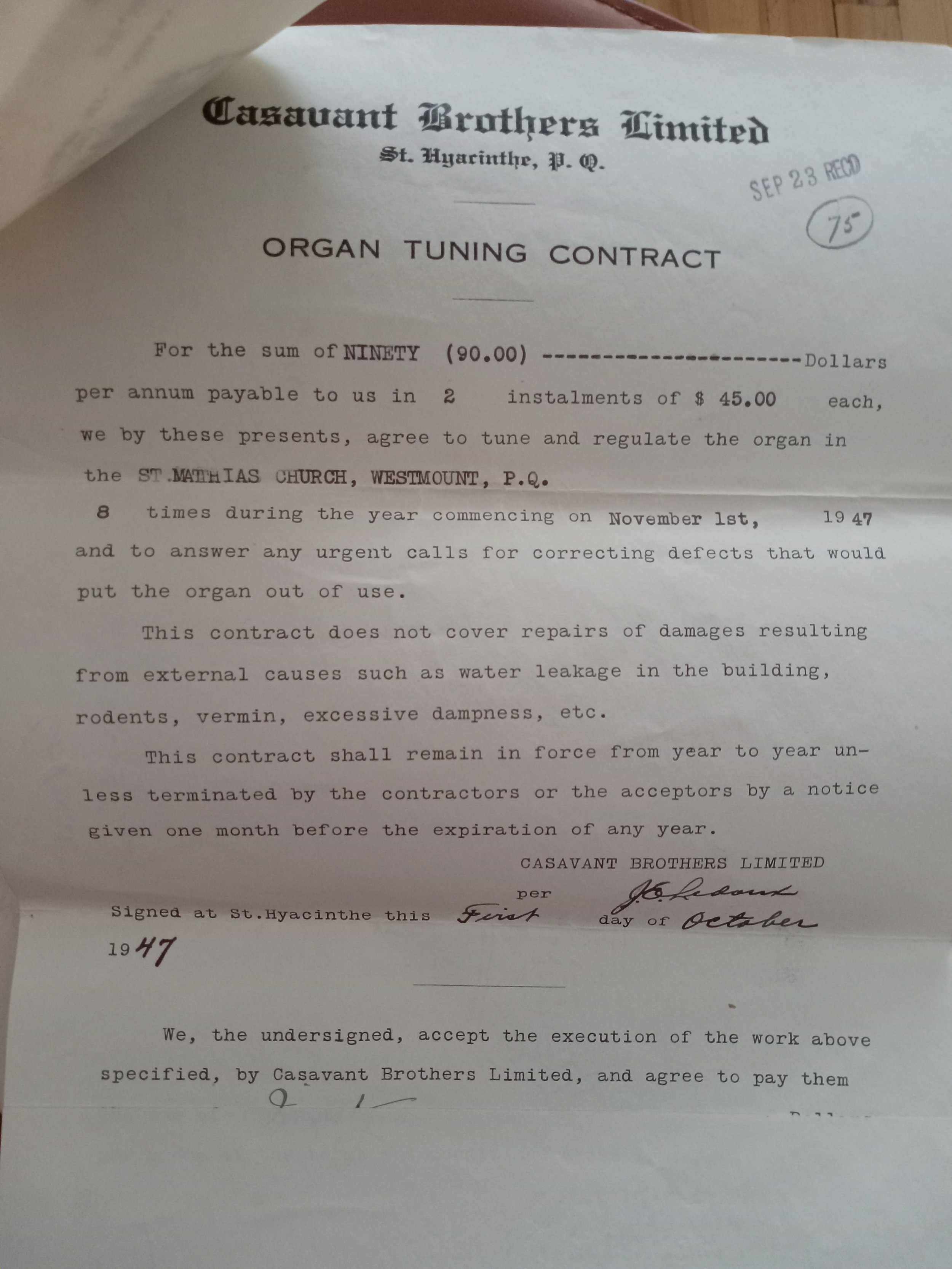

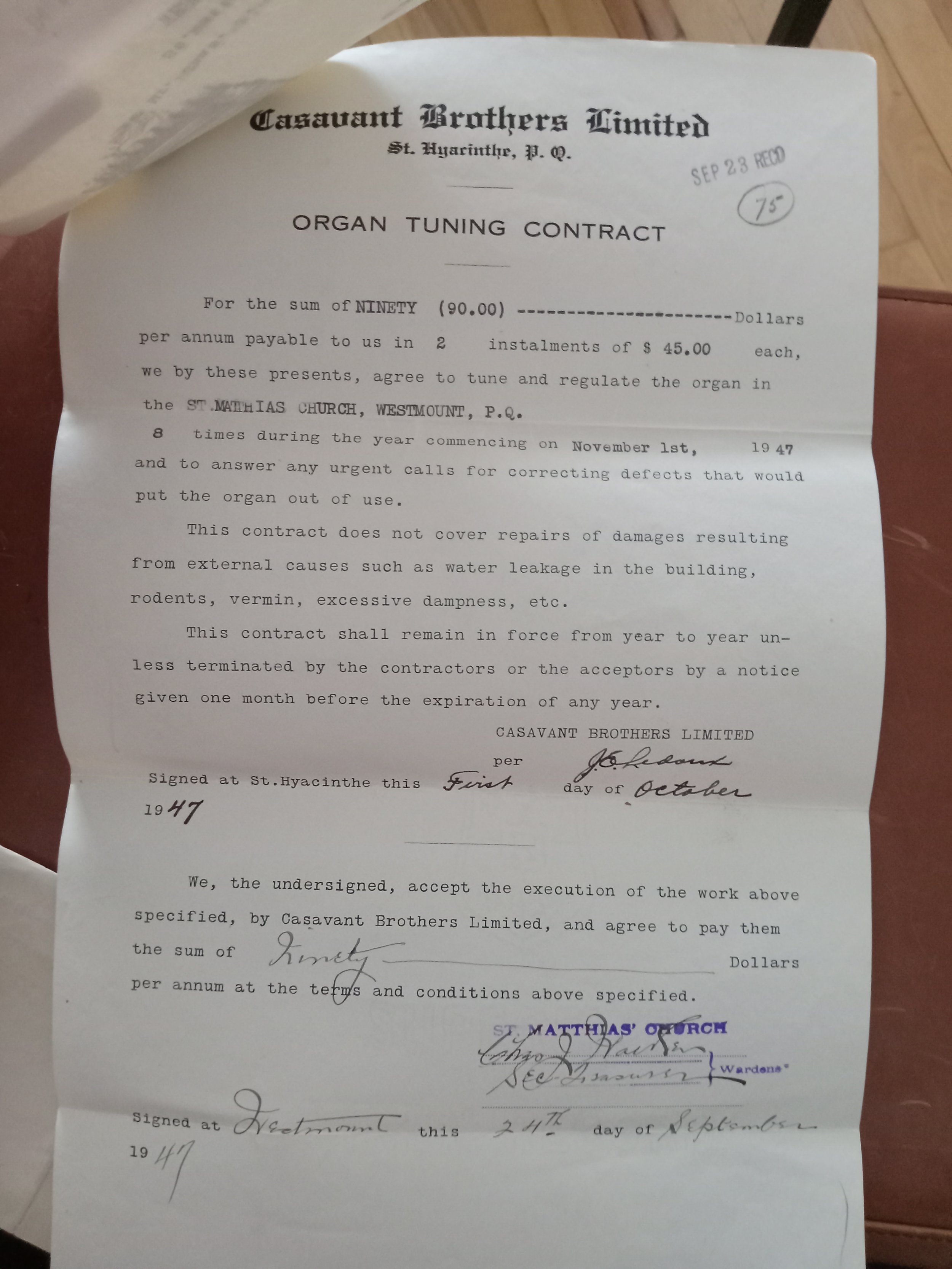

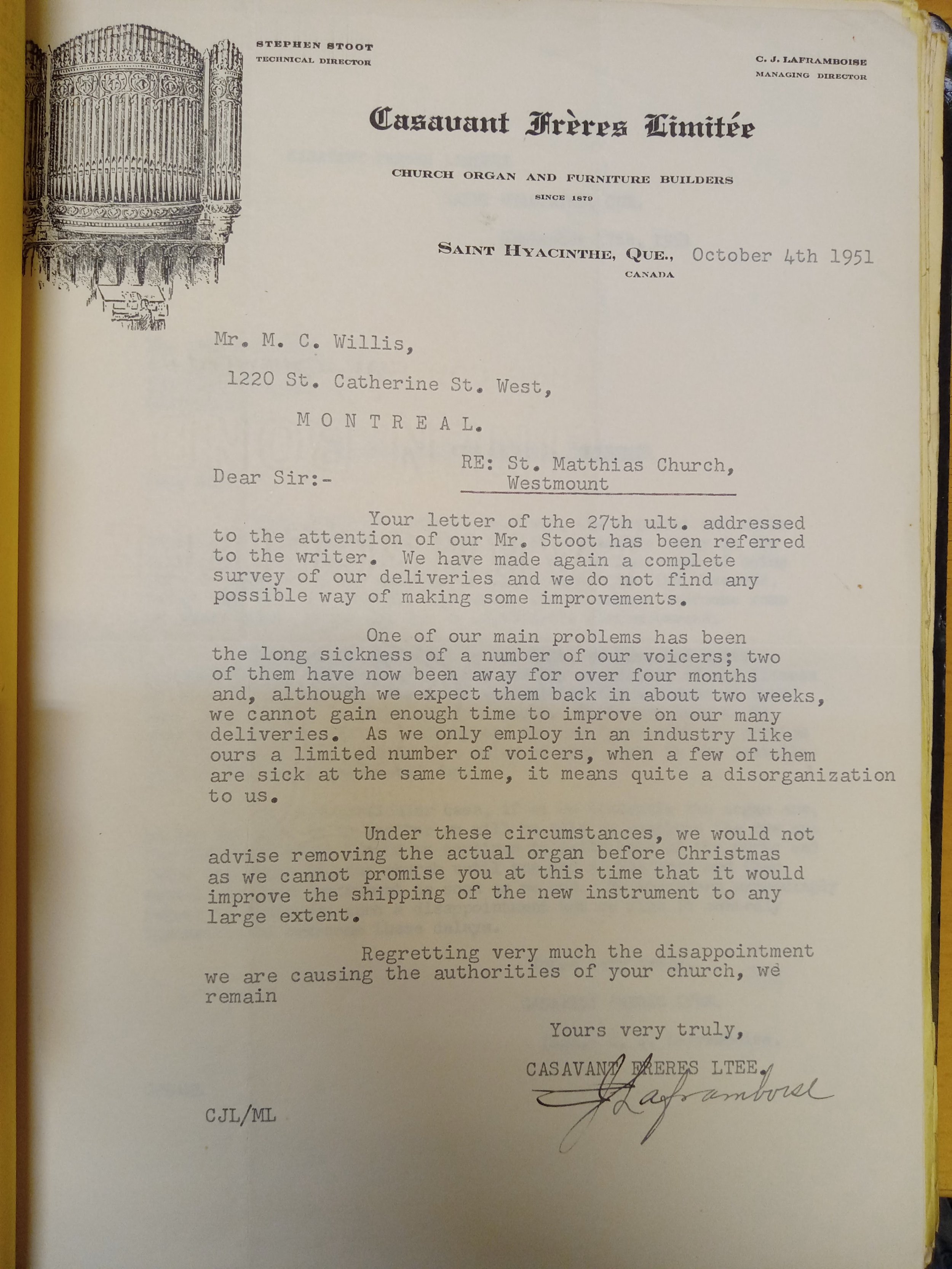

Maintenance of the organ eventually settled with Casavant Freres, a Montreal-based organ building firm that had been founded in 1879 and continues to build instruments to this day. Casavant was an early adopter of electro-pneumatic organs, building their first in 1892. Although they boast of being the first builders in Quebec to build according to the Organ Reform Movement that had begun to sweep Europe in the early 1930s, prompting a return to mechanical action, they would go on to be the builders of an electro-pneumatic organ for St. Matthias’ well into the reform.

Organ 3, or 3.5, or maybe even 4

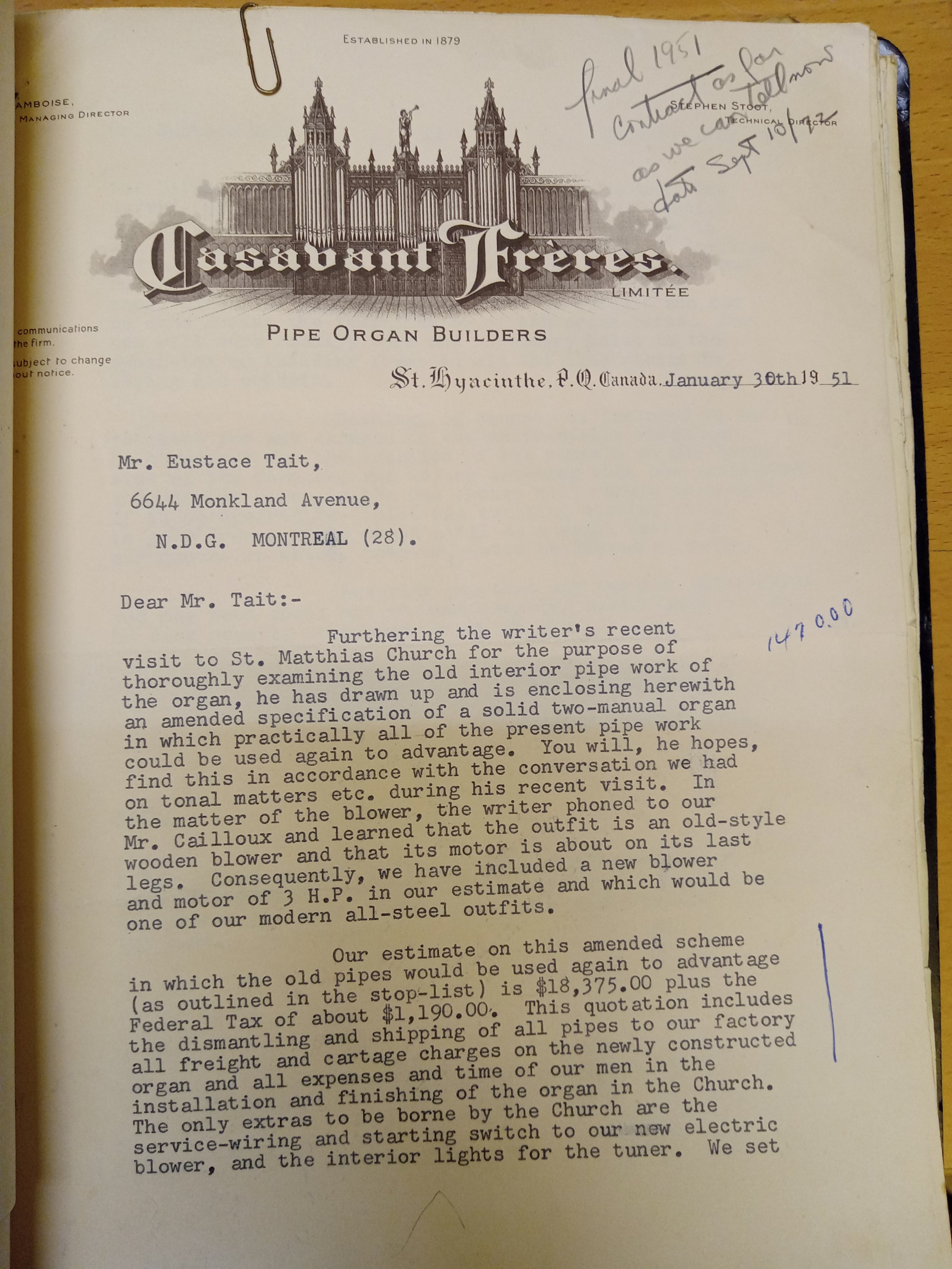

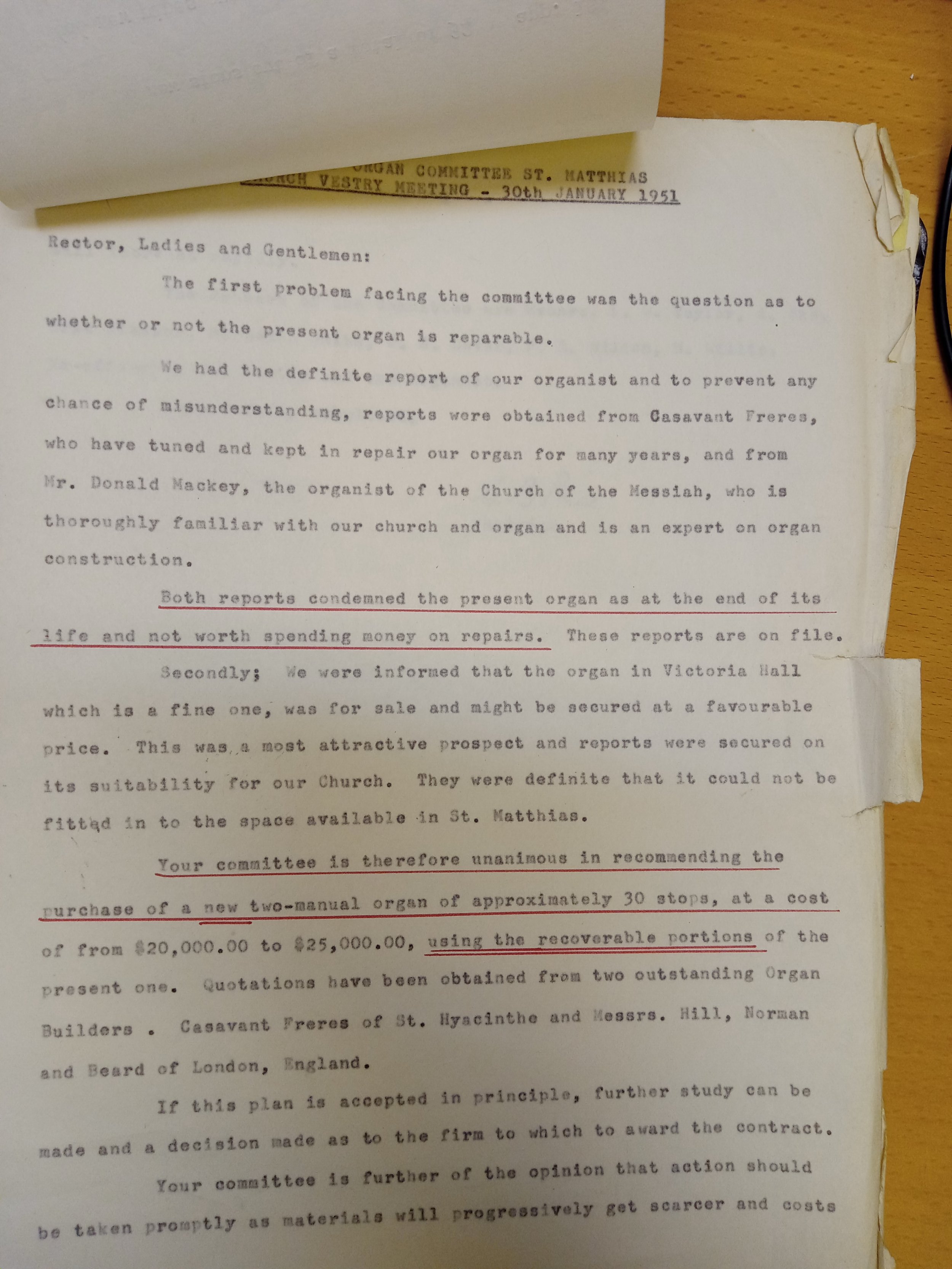

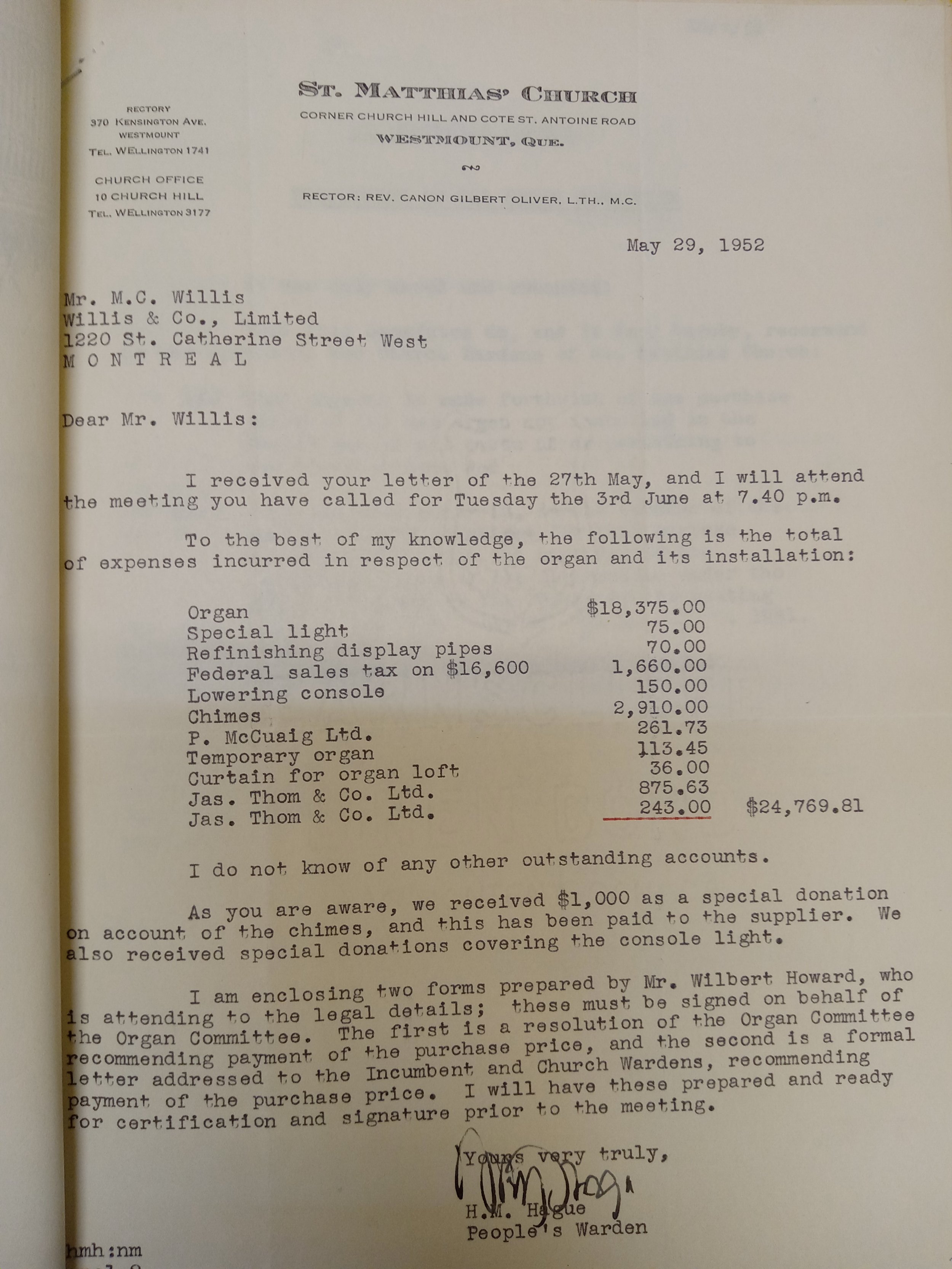

Thanks to the maintenance work of these various firms, but especially Casavant, the 1893 organ continued to be the centre of St. Matthias’ music through the transition to the new building and both world wars. But, by 1950, the organ was clearly on its last legs. The Wardens struck a committee to examine how best to “improve the organ situation,” which did not have much to report to Vestry 1951, which was held in January. By March of that year, Casavant had submitted a quote for a $23,000 organ (almost $260,000 today) and by June of 1952, St. Matthias’ had borrowed $20,000 ($225,000) against the church property. The Wardens reported to Vestry in January 1952 that the building was already underway. And even with that major expense, Casavant re-used parts of the previous organ(s), contributing to the instrument soon accumulating high maintenance costs.

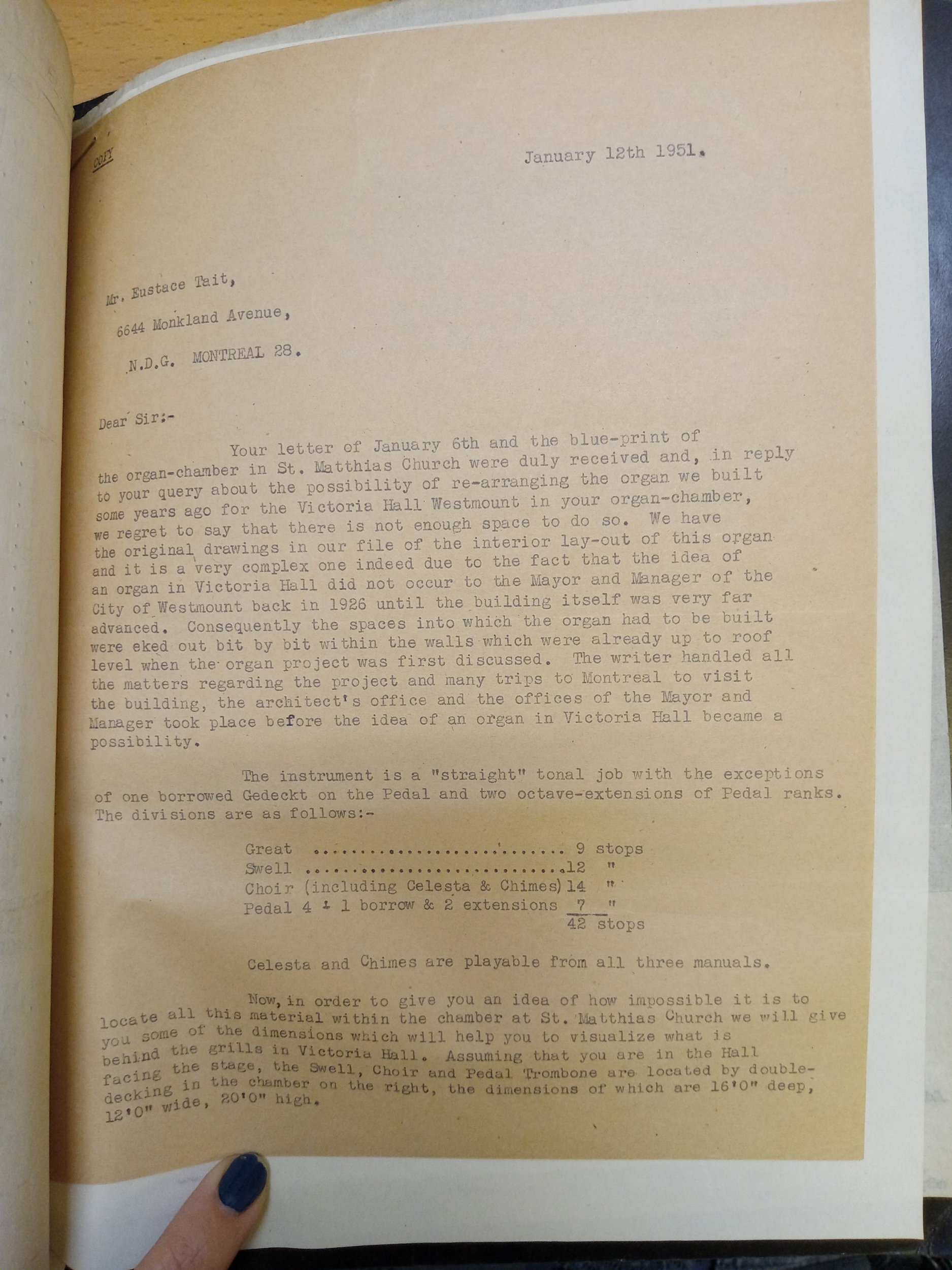

But between Vestry reports in our archives, the 1950-52 Organ Committee compiled its own massive dossier, which reveals the lengths to which they went to try to avoid adding yet more debt to St. Matthias’ plate in the years where the 1935 Parish Hall was still being paid off. They first investigated the chances of repairing the organ - Casavant indicated that even regular maintenance had reached the end of what it could be expected to do. Then, they considered whether the organ of Victoria Hall would suit - the short answer was “it won’t fit,” the longer answer having to do with the labyrinthine structure the Hall’s organ had needed when it was retrospectively added to the building design in 1926. Finally, “using the recoverable portion of the present" one,” the new organ was contracted. Delivery was delayed as Casavant’s workforce was struck down by flu in early 1951, but finally, just in time for the loan to be authorised and payment to be due, the new-old organ was installed.

Organ 4 or 5 or maybe 6 The Last Organ

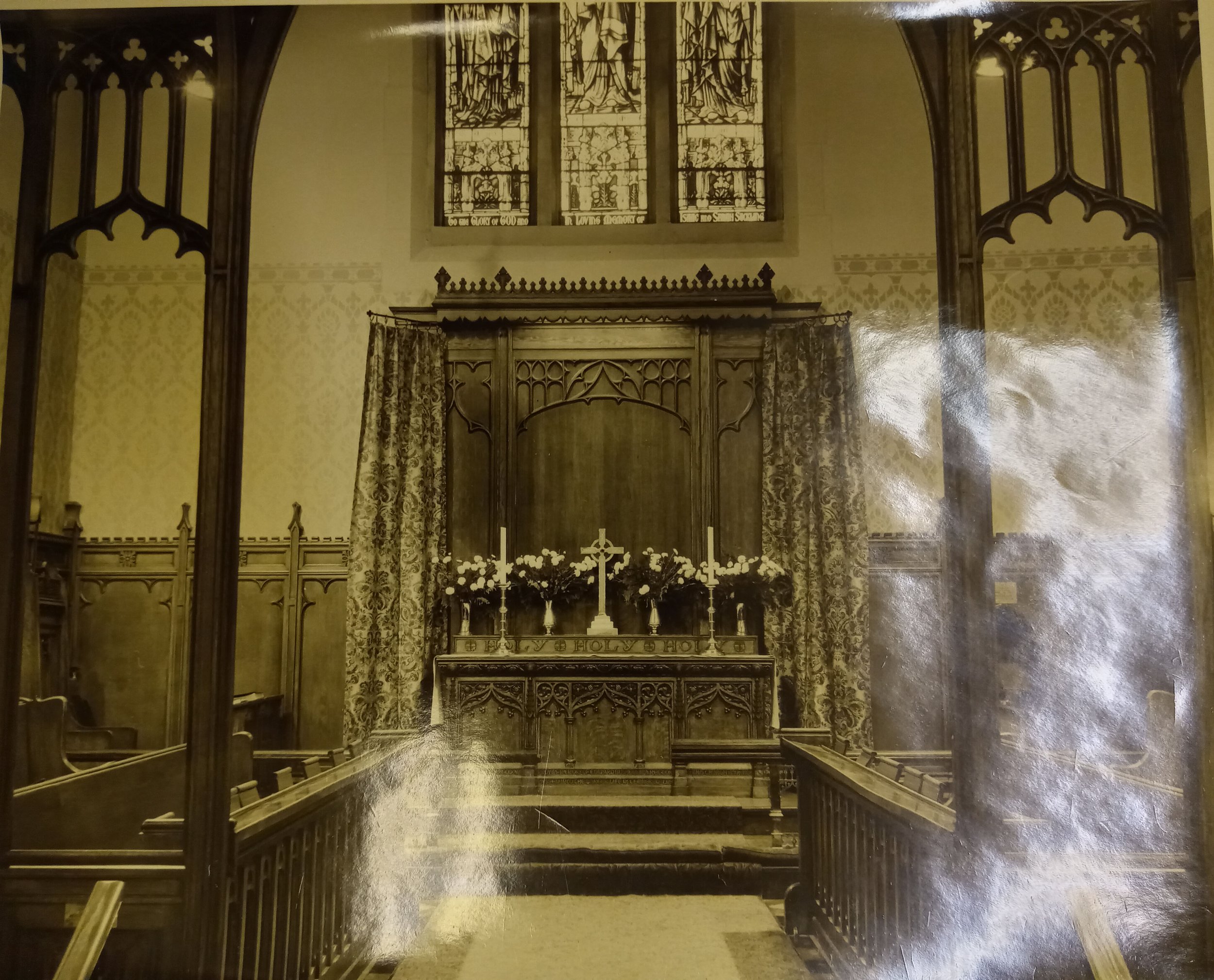

One of this first questions Scott answered in the course of our work together was “why, merely 20 years after indebting itself enormously, would St. Matthias’ decide to build a whole new organ?” The answer lies in two places: Firstly, the Organ Reform Movement’s return to mechanical-action tracker organs was already demonstrating the longer lifespan of mechanical instruments compared to the 1952 electro-pneumatic, and the philosophy of music that went along with this movement was decrying the quality of sound possible when the organ was “stuffed into a closet,” to use Scott’s evocative image. Secondly, the Men & Boys Choir was expanding rapidly in size. Because of liturgical shifts in the beginning of the century, the chancel was no longer home to ranks upon ranks of vested clergy, and was looking rather empty. Choirs began to vest instead, and to take their places in the chancel. As these images from 1934 and the late 1960s show, the seating in the chancel took up quite a bit of space! But even it was not enough to accommodate 50 boy choristers plus probationers, and 20-30 adults. These two factors, one from the larger musical world and one from within the church, led St. Matthias’ to opt to give itself the most lavish 100th anniversary present it could imagine.

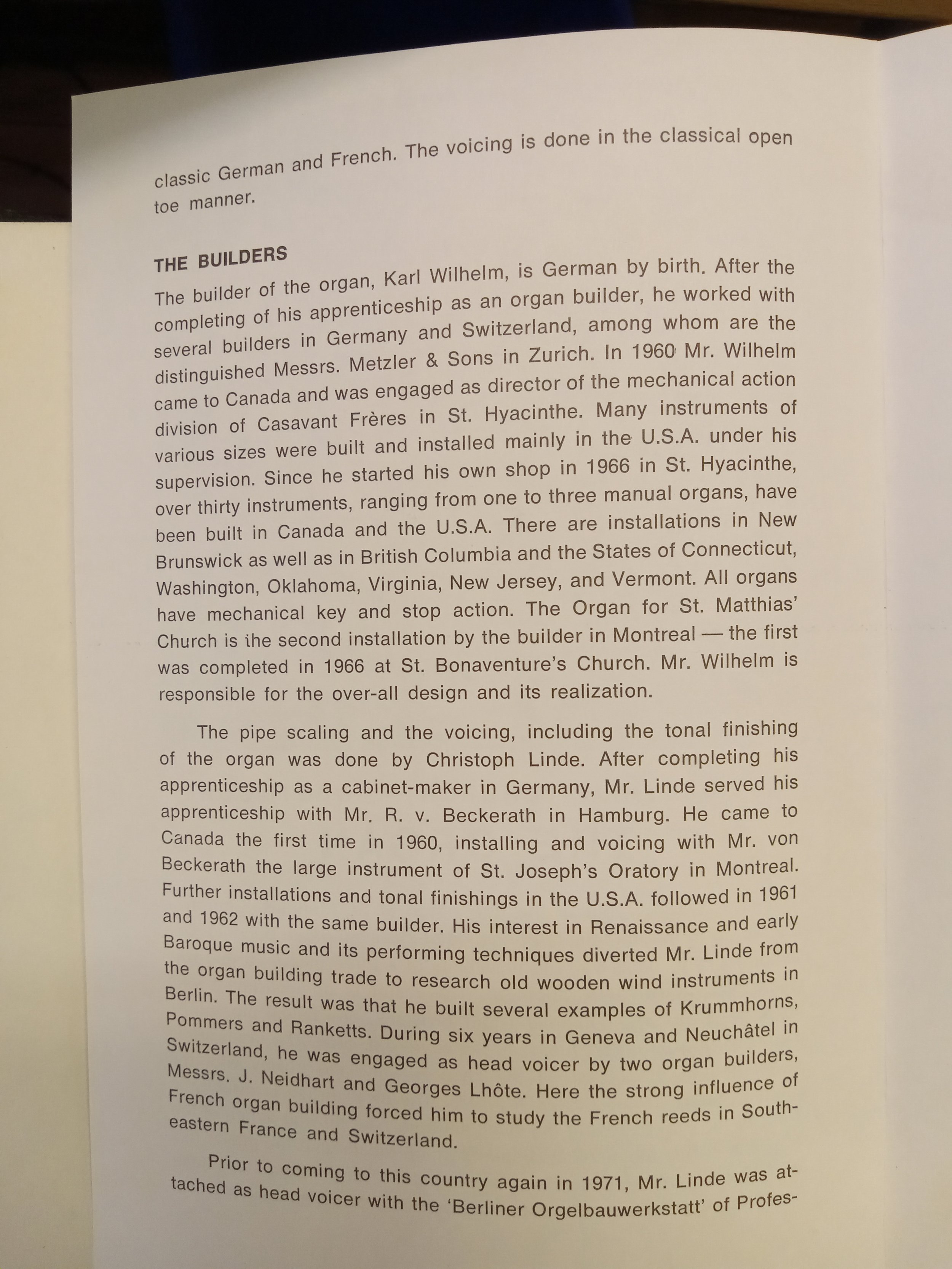

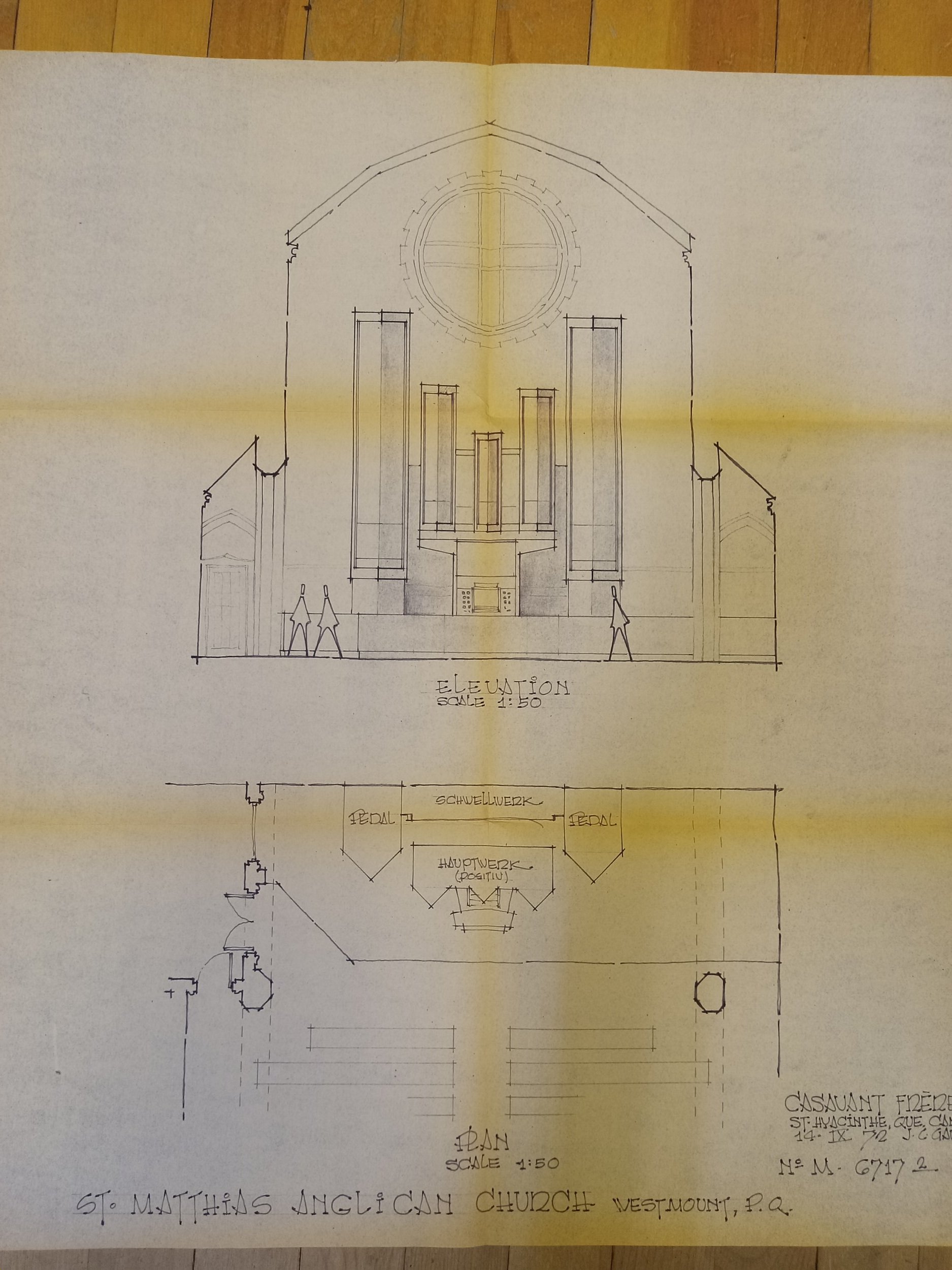

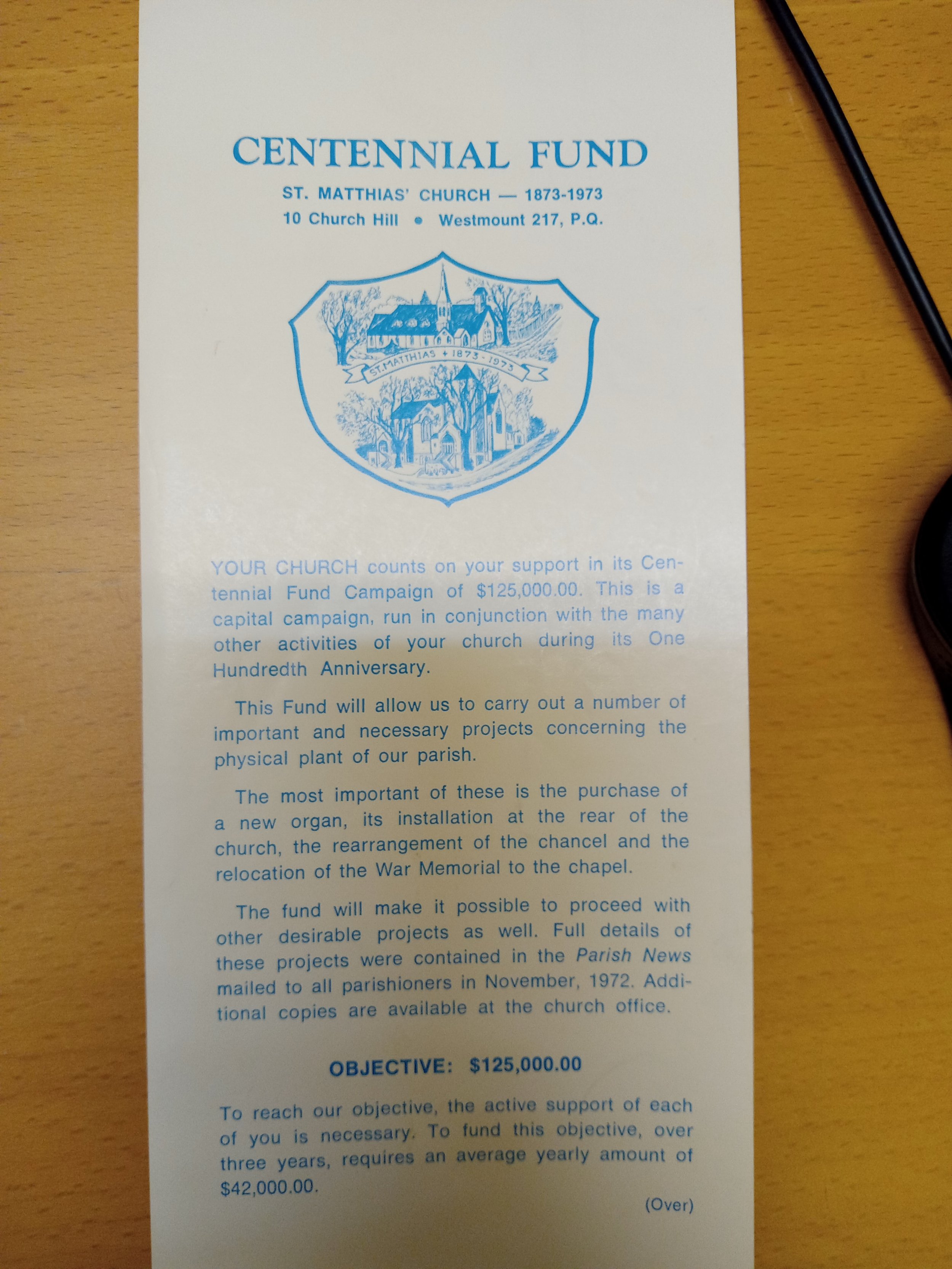

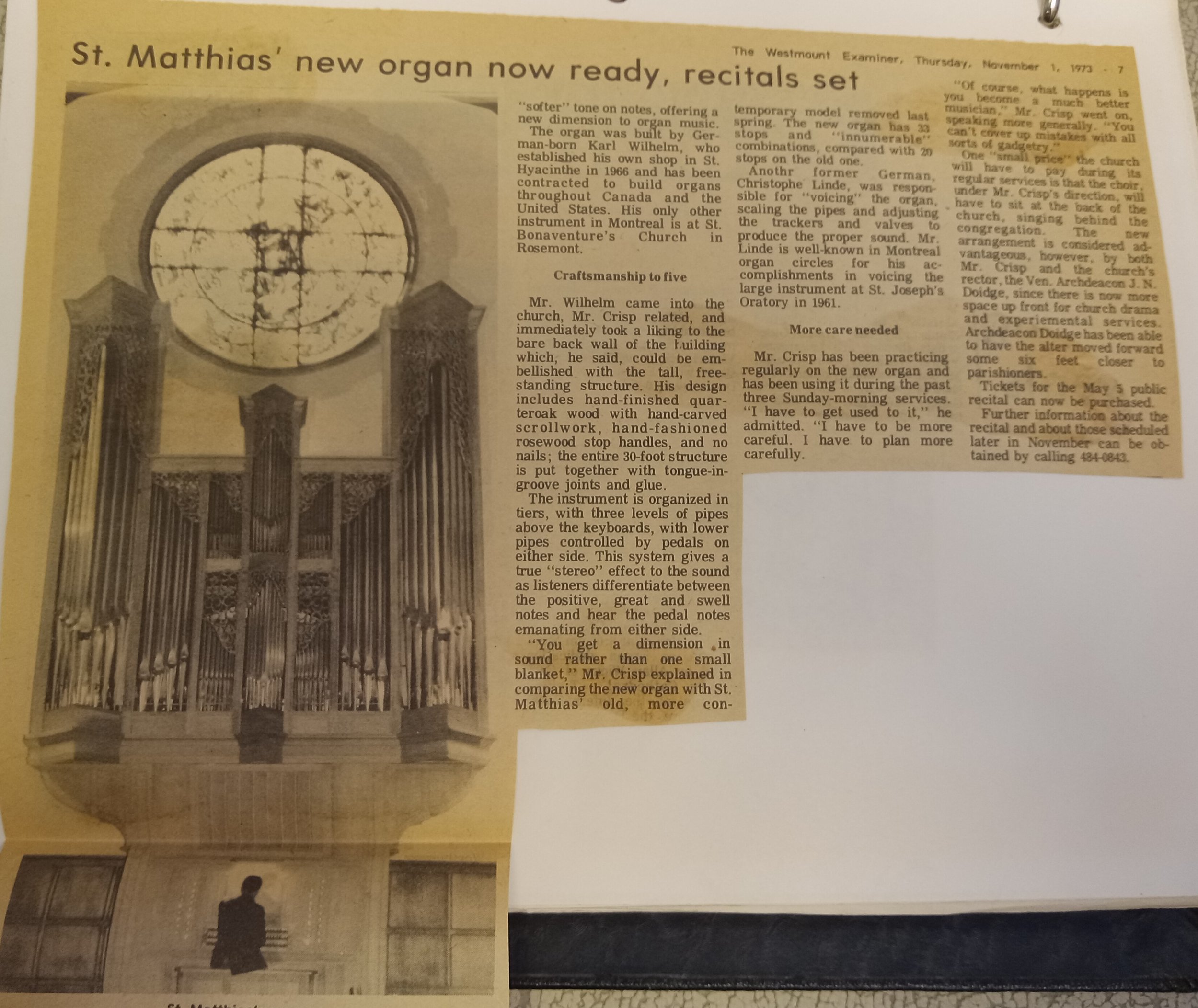

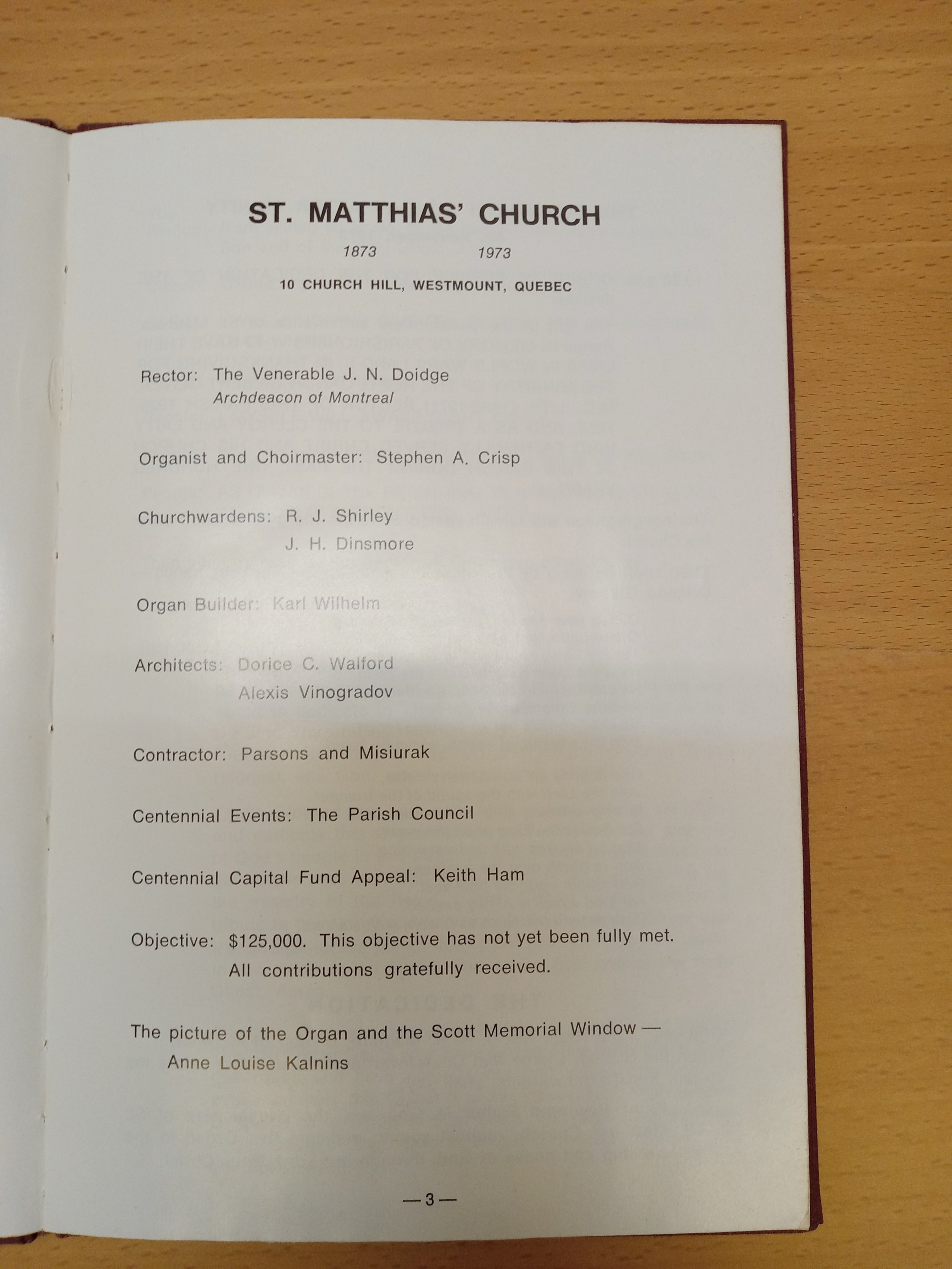

Casavant Freres submitted a lovely organ plan, which bears striking resemblance to our organ today, but St. Matthias’ ultimately went in a different direction: up-and-coming Karl Wilhelm, who had been working in North America for Casavant from 1960-1966, and who had, in 1966, opened up his own studio in St-Hyacinthe. By 1990, he had built a staggering 124 organs, St. Matthias’ being one of them. To pay for it and the various architectural alterations that were needed to complete the move to the back of the church, St. Matthias’ set itself an ambitious fundraising goal of $125,000 (nearly $825,000 today).

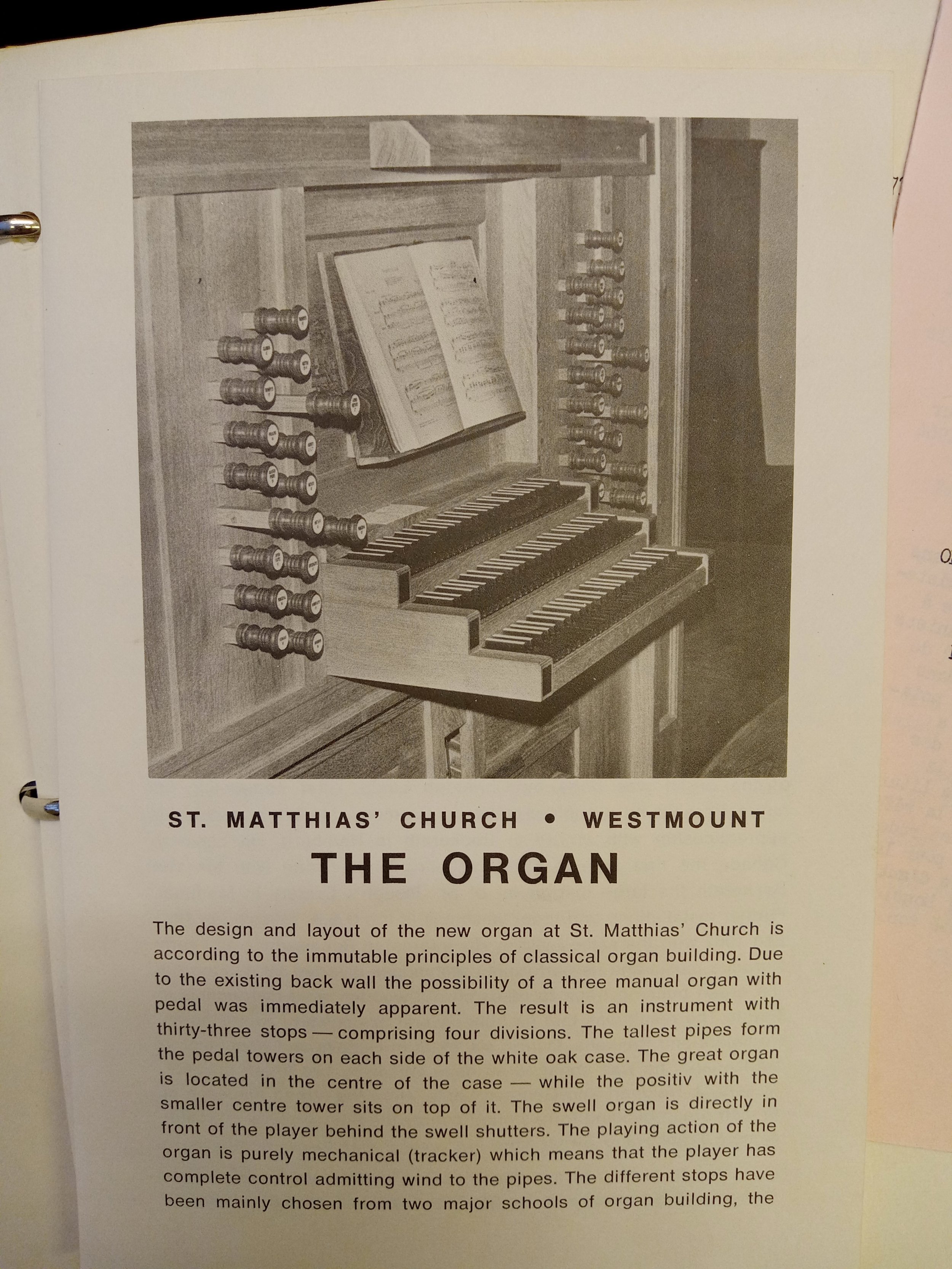

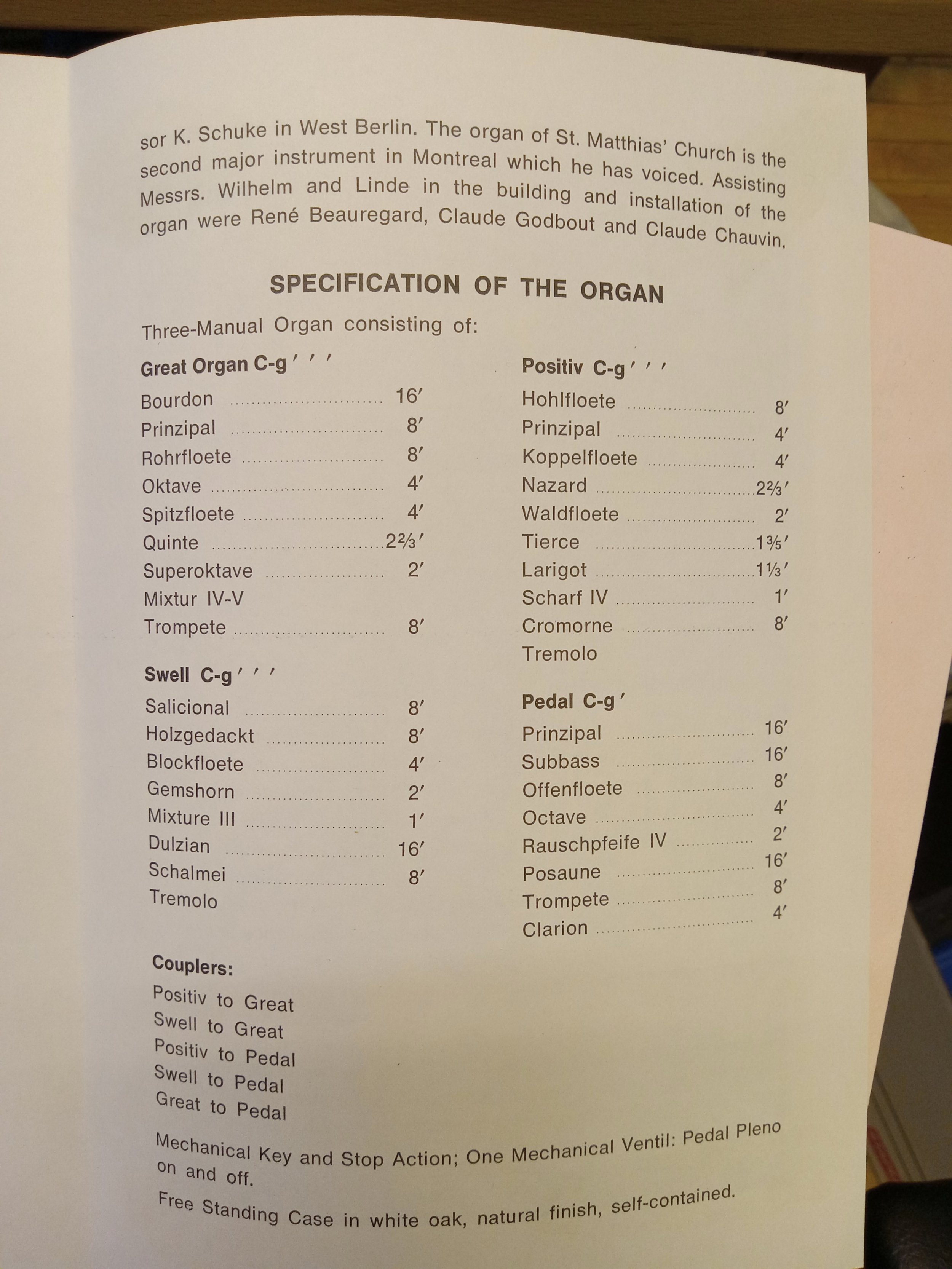

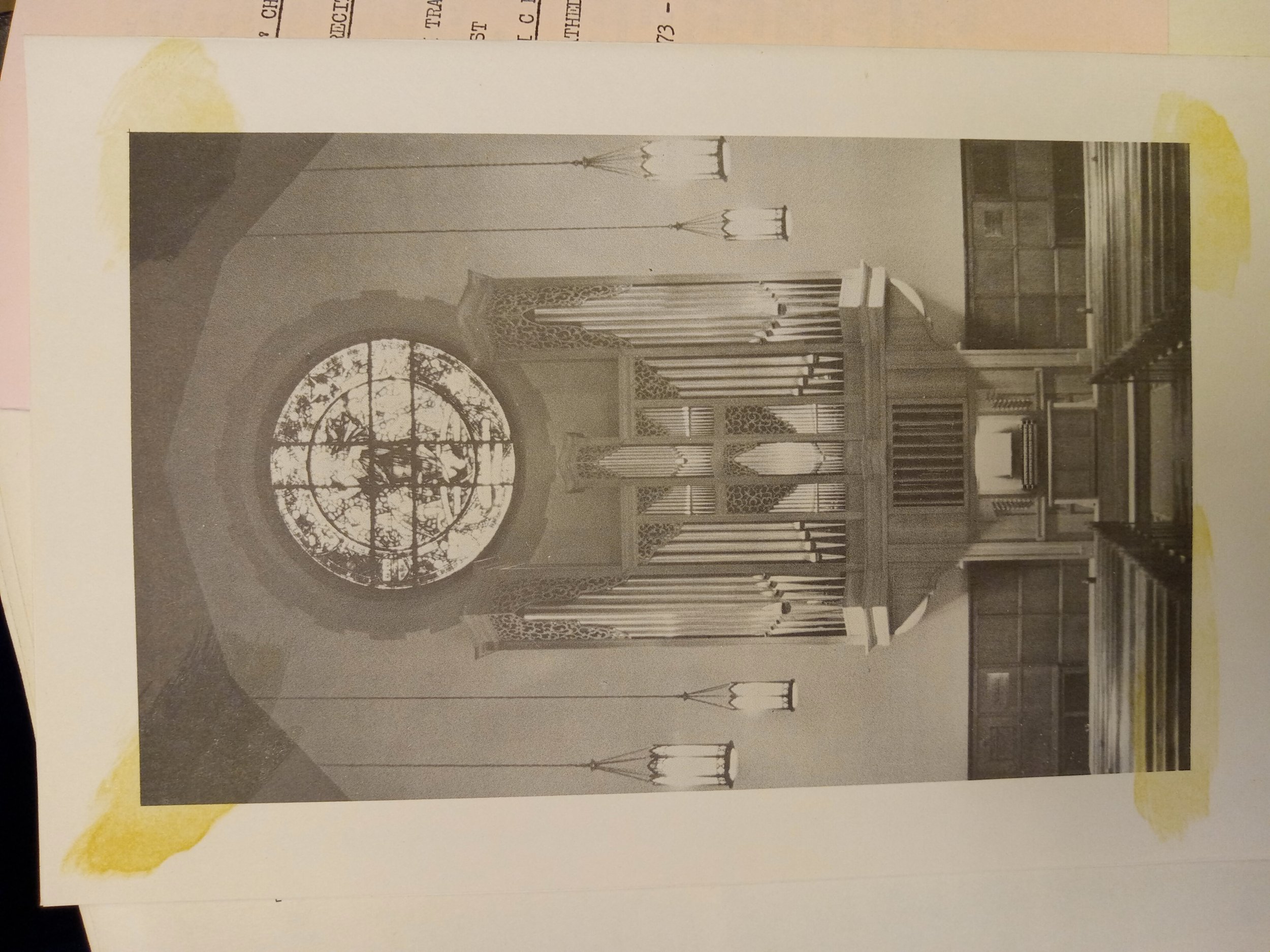

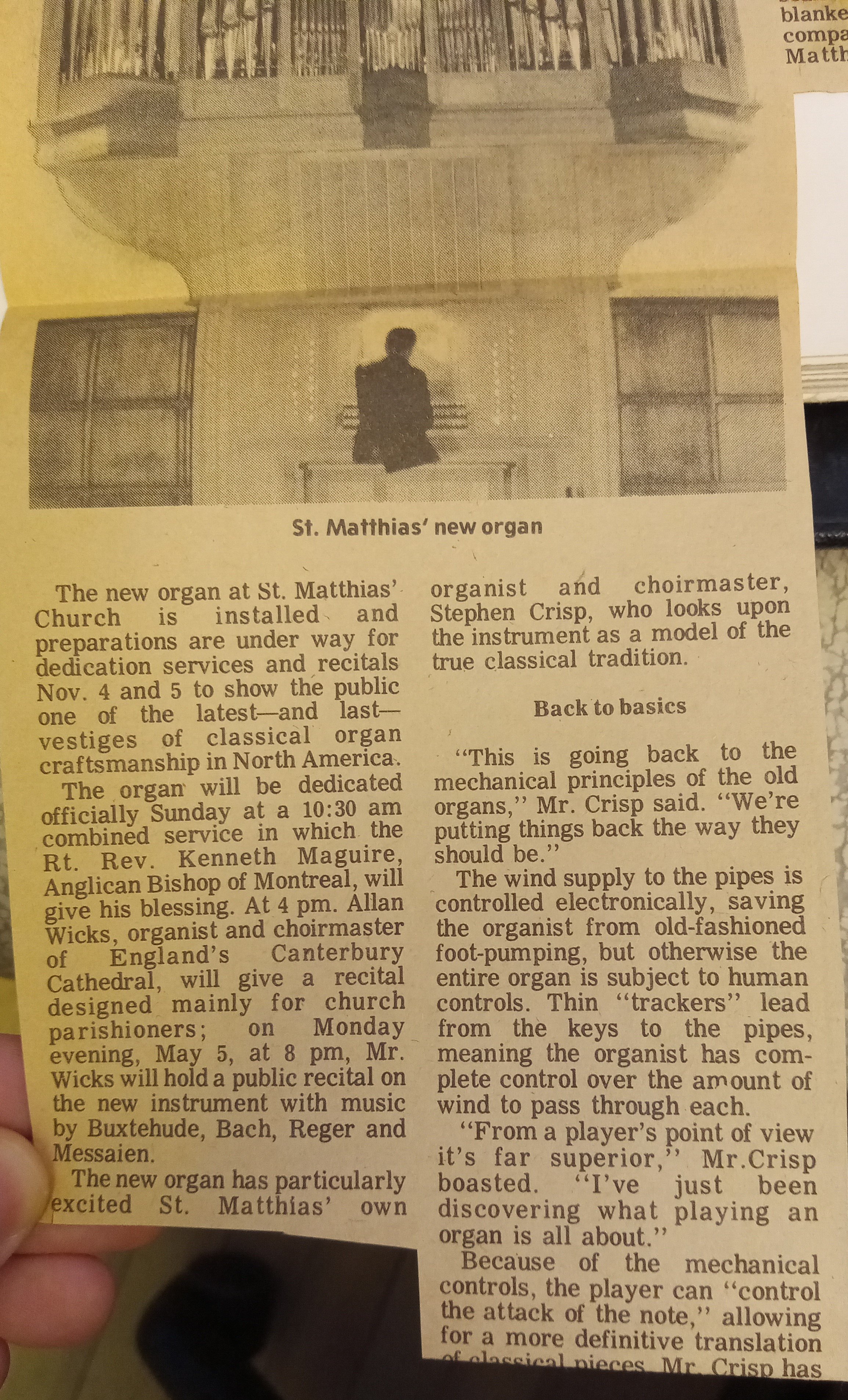

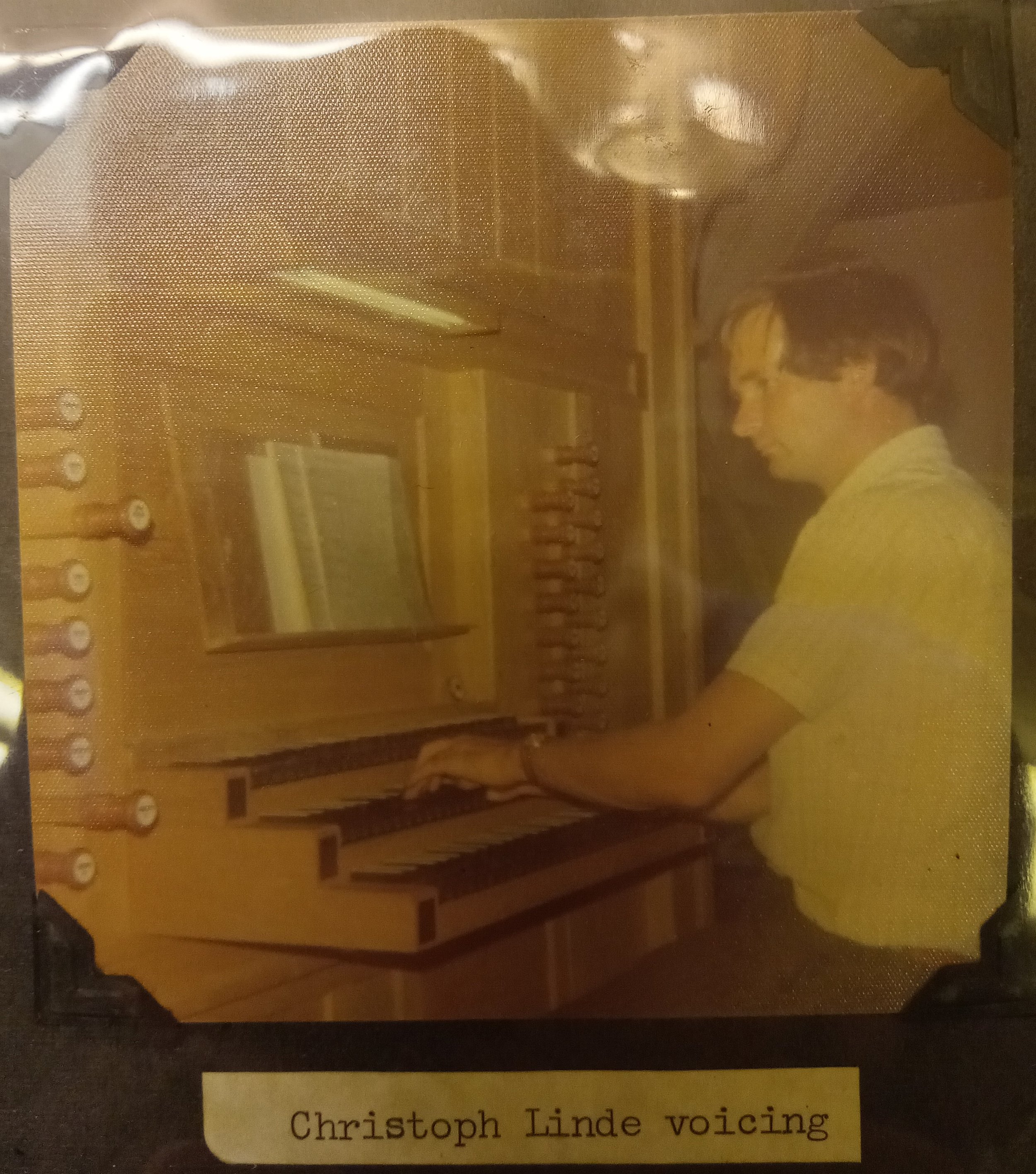

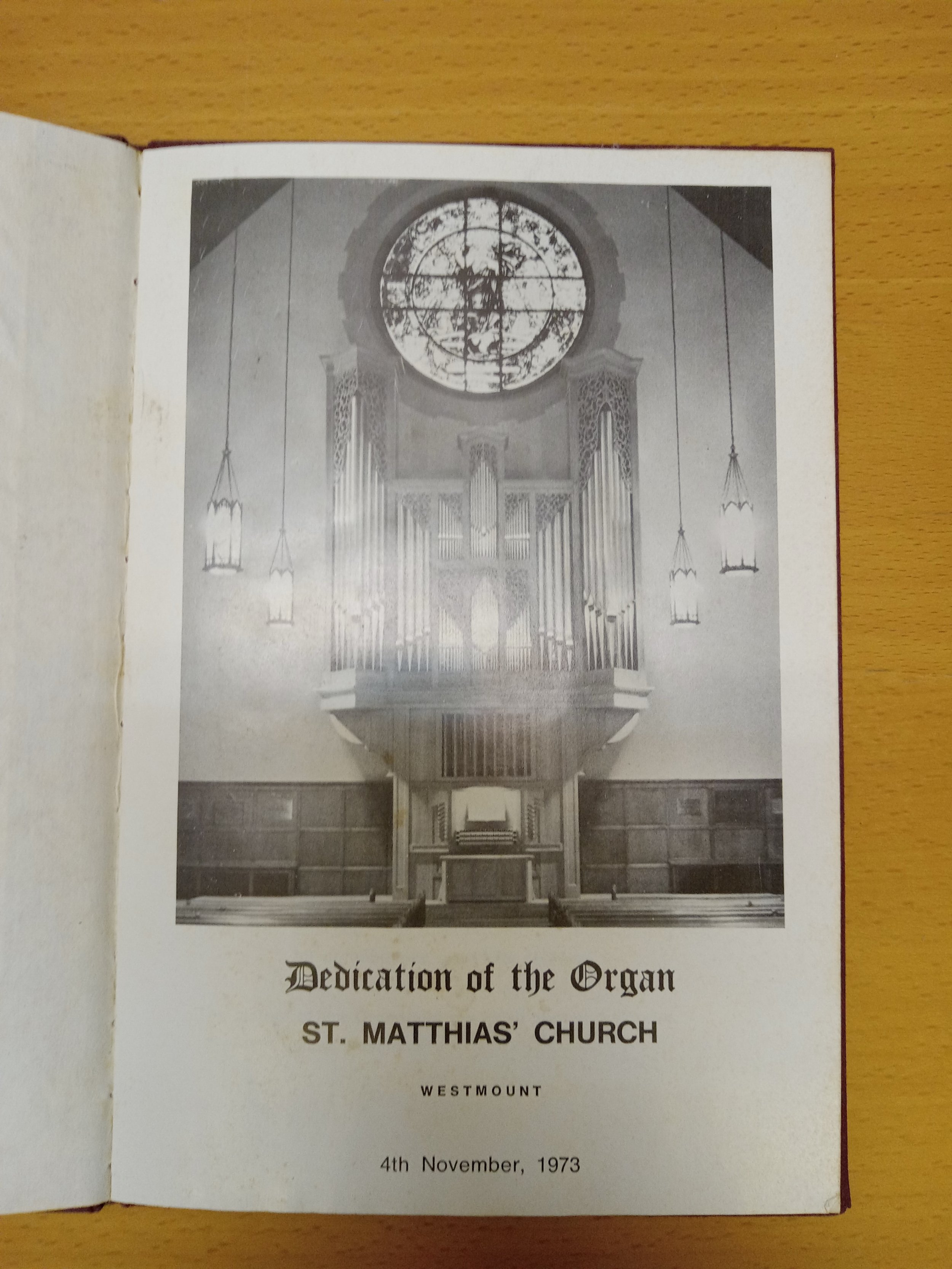

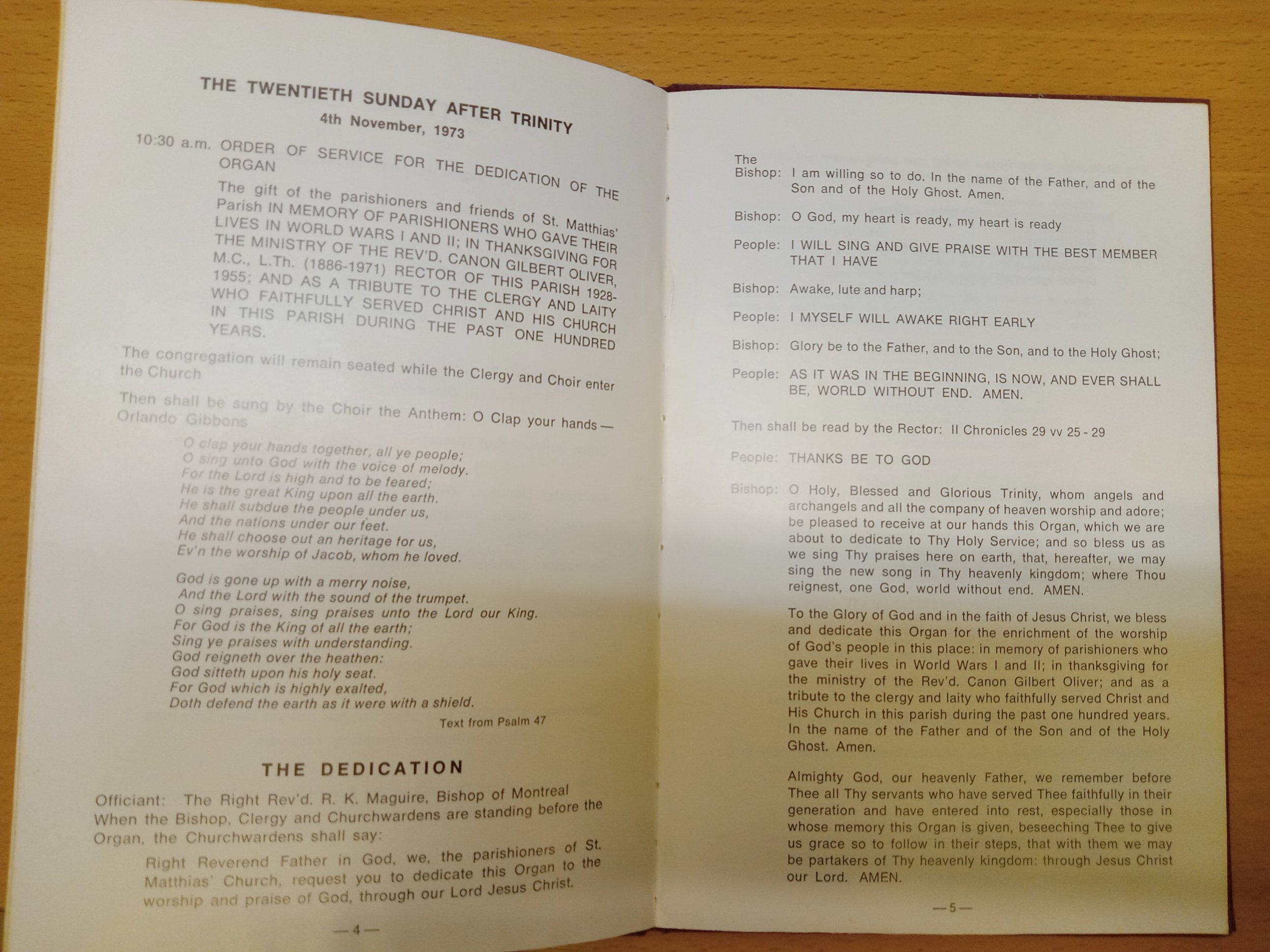

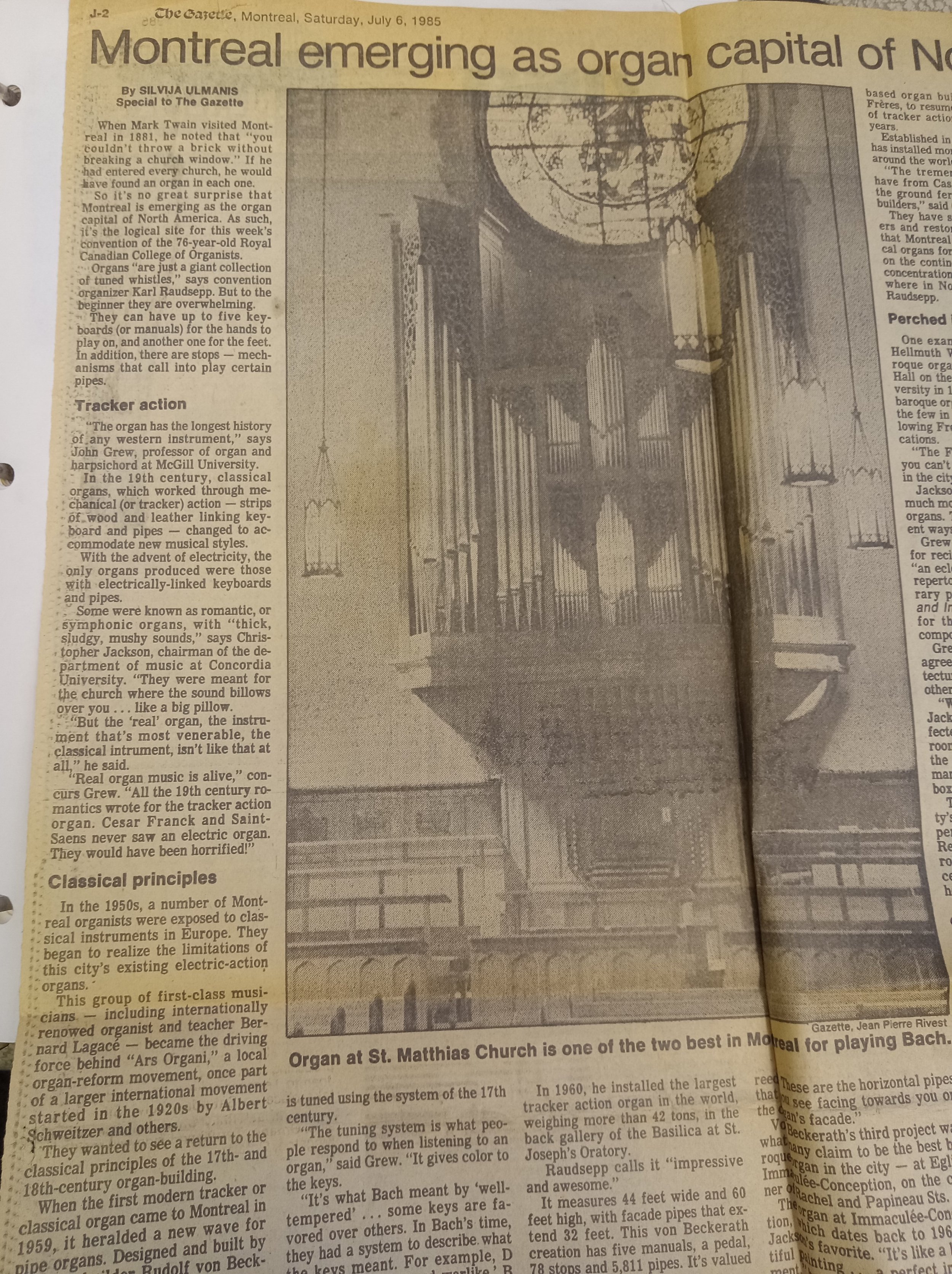

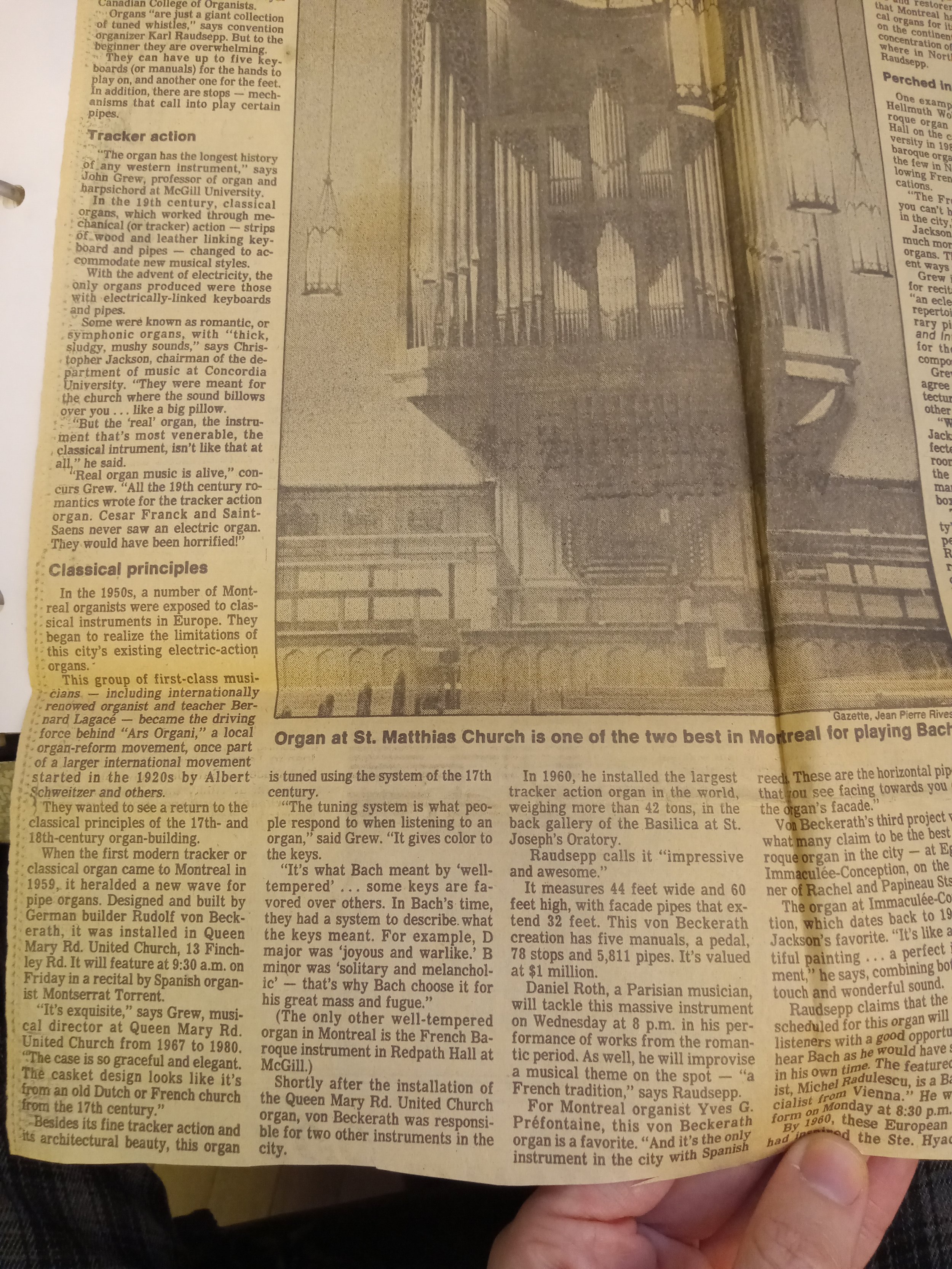

In the inaugural service’s technical insert, the organ is praised for combining “two major schools of organ building,” and the skills of both Karl and the organ’s voicer, Christoph Linde, are extolled. Voicing is another of those technical elements that required some explanation; in the video at the top of this page, Scott goes into some detail on how voicing works, but the gist of it is that the voicer is the one who carefully, pipe-by-pipe, makes minute adjustments to the metal involved to create the perfect sound. Scott says that Cristoph’s voicing is what makes St. Matthias’ organ such a beautiful instrument. But as the Westmount Examiner noted the week of the organ’s unveiling, a large part of the thanks is also due to the way that Karl crafted the organ around St. Matthias’ space, considering both the shape it would take to accent the Rose Window, and the particular acoustic qualities of the sanctuary.

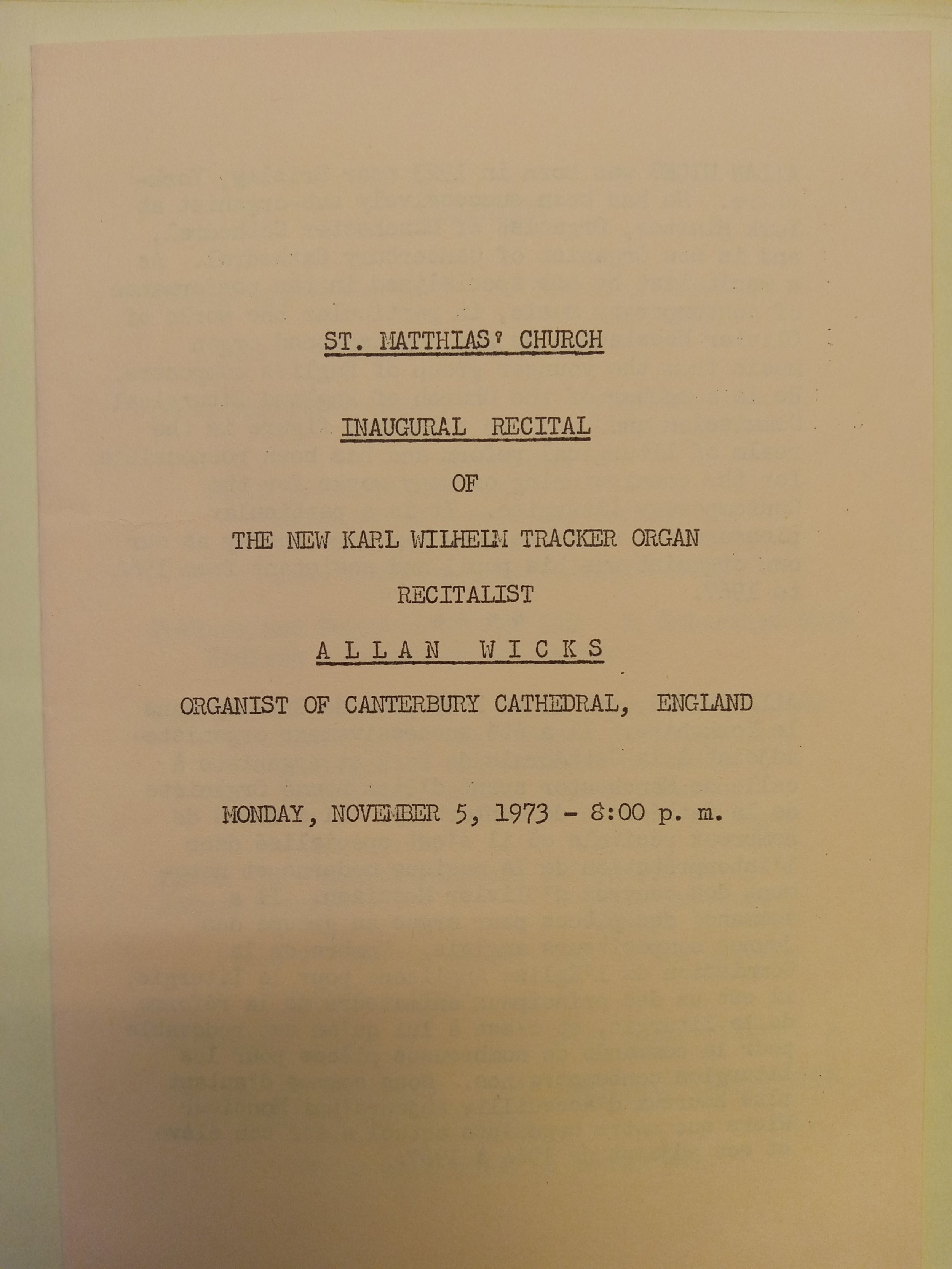

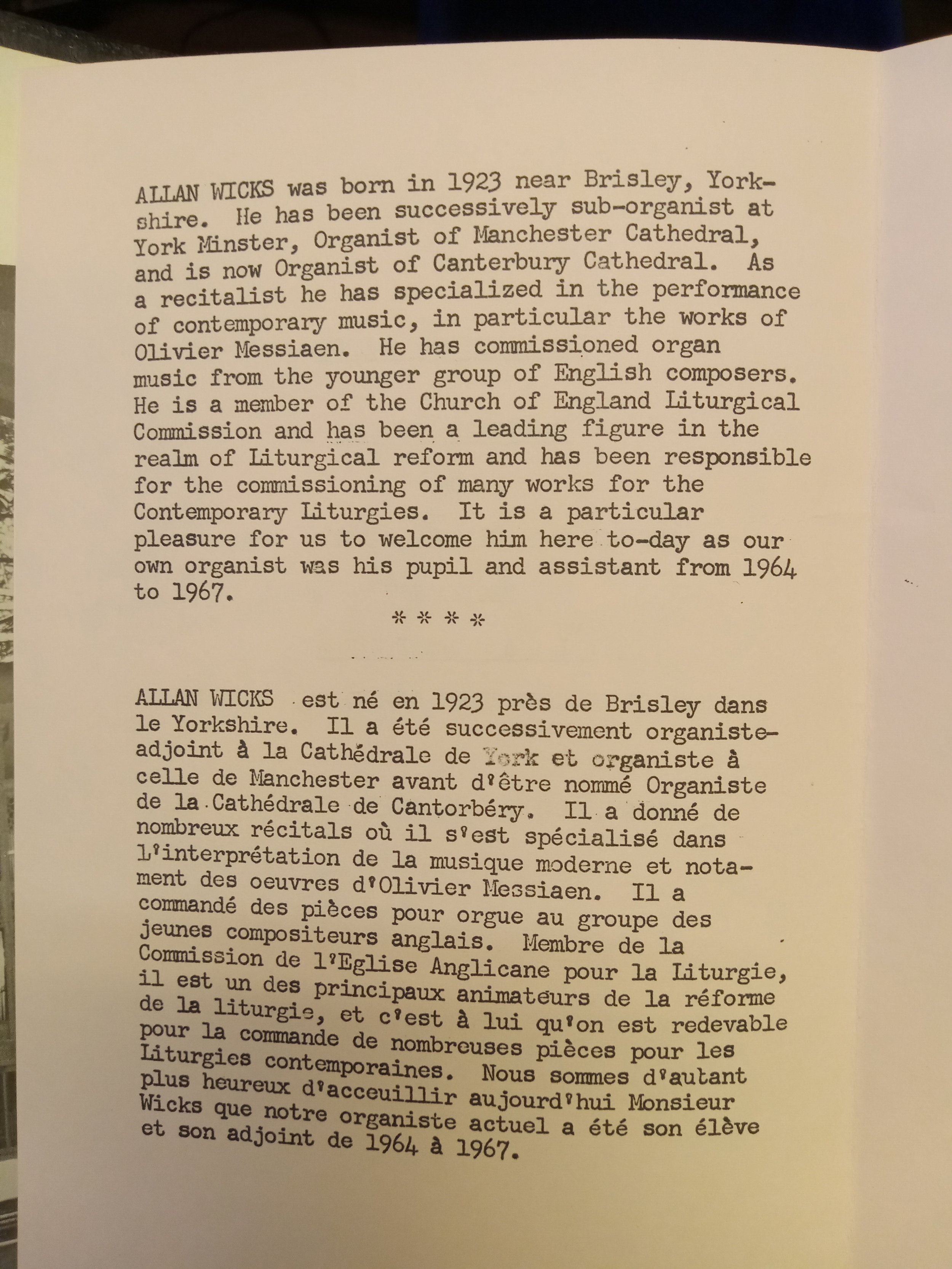

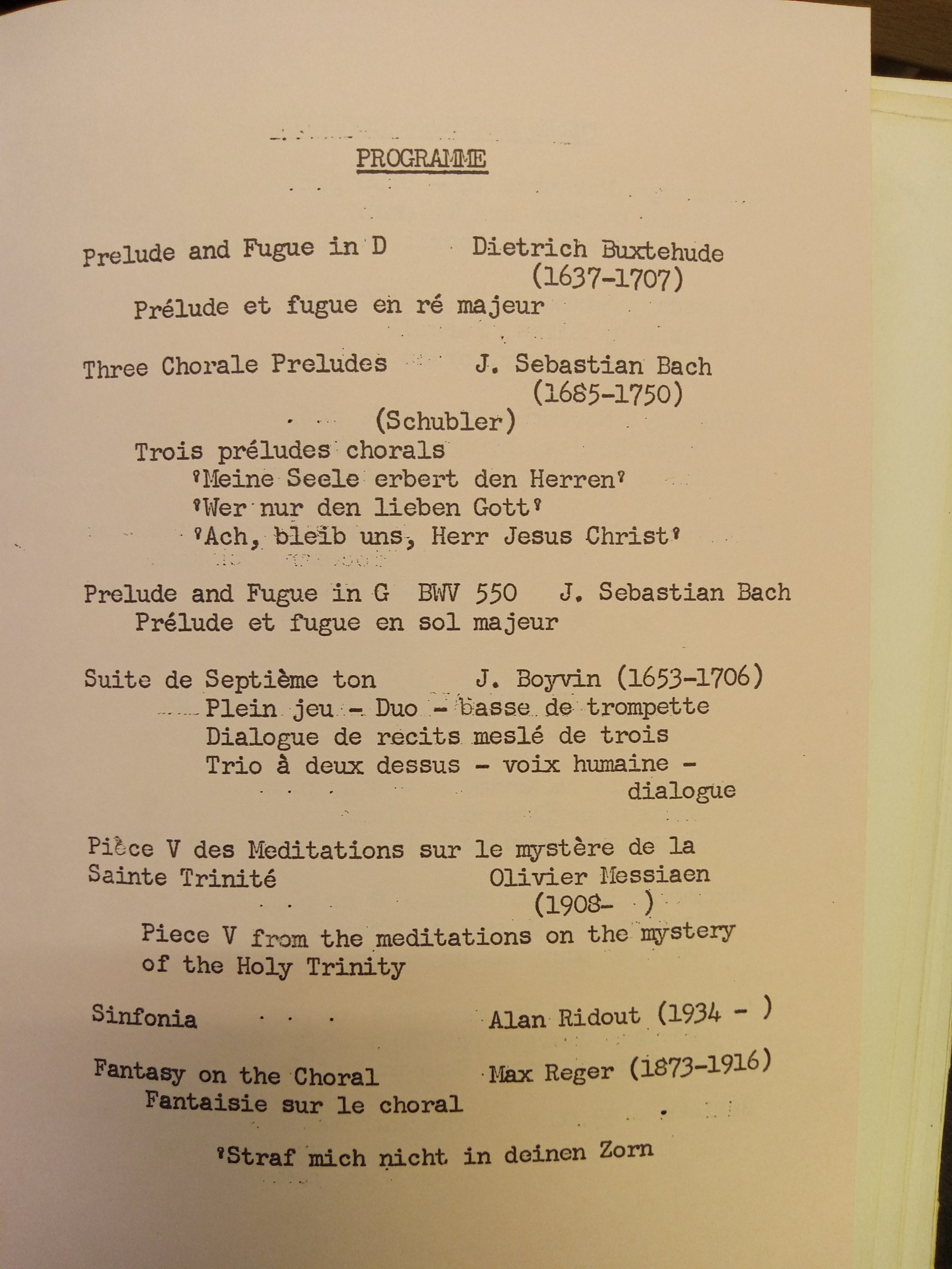

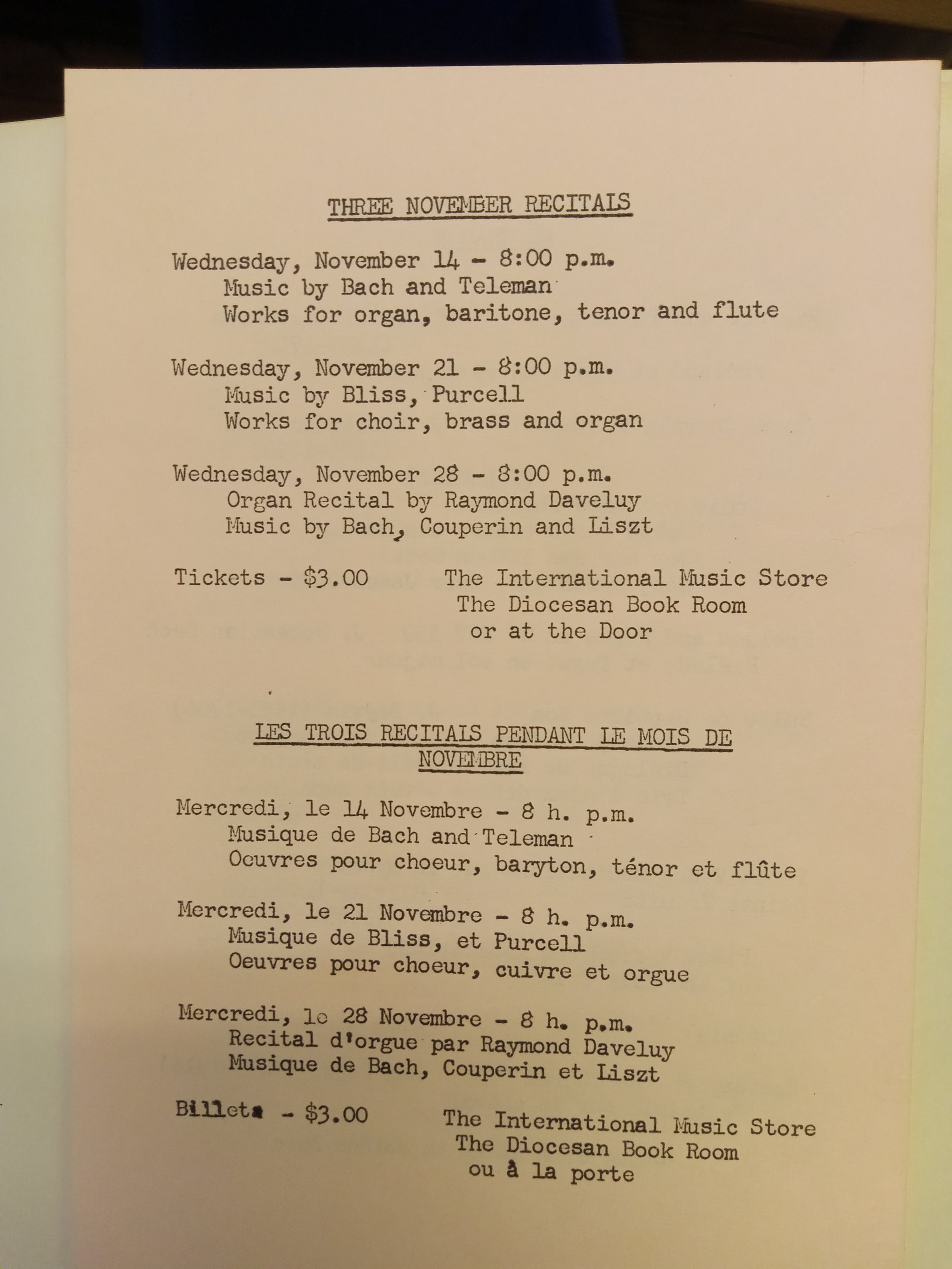

A review of the inaugural concert, in the Montreal Gazette, noted a downside of the particularity that an organ requires: it becomes more suited to playing music by composers of a particular era. A later article, from 1985, celebrates this fact: the 1973 organ is unabashedly Baroque, allowing us to hear what Bach and his contemporaries would have sounded like on their own instruments. But, as Jacob Siskind discovered, that makes it less ideal for interpreting Romantic works. Allan Wicks, the organist of Canterbury Cathedral at the time and the invited musician for the inaugural concert, had chosen a program that focused on the era of the organ’s particular strength, but had also included pieces from other eras to demonstrate that, although it is a “Bach” organ, it nevertheless has range and capacity to meaningfully interpret a wide range of music. Allan would go back to England to recommend to Canterbury’s Dean that Karl Wilhelm be engaged for their organ-building needs! Today, while Scott supplements the organ with a grand piano and electric keyboard today, he does not hesitate to select choral and instrumental pieces from across the span of church history.

The 1973 organ is a masterpiece of craftsmanship, and is the first organ we have had that has not needed consistent significant maintenance – its initial expenditure gave St. Matthias’ the largest deficit in its history, but it has more than paid for itself in the years since. And, of course, it continues to animate the space with the kind of rich, orchestral music that only organs can produce.