October 22nd: Cracks in the Glass

St. Matthias’ was officially founded as a mission of St. George’s, Place du Canada, in 1873, which means our community is 150 this year! For the next 12 months, we’ll be diving into the archives to shine the spotlight on particularly interesting parts of our history.

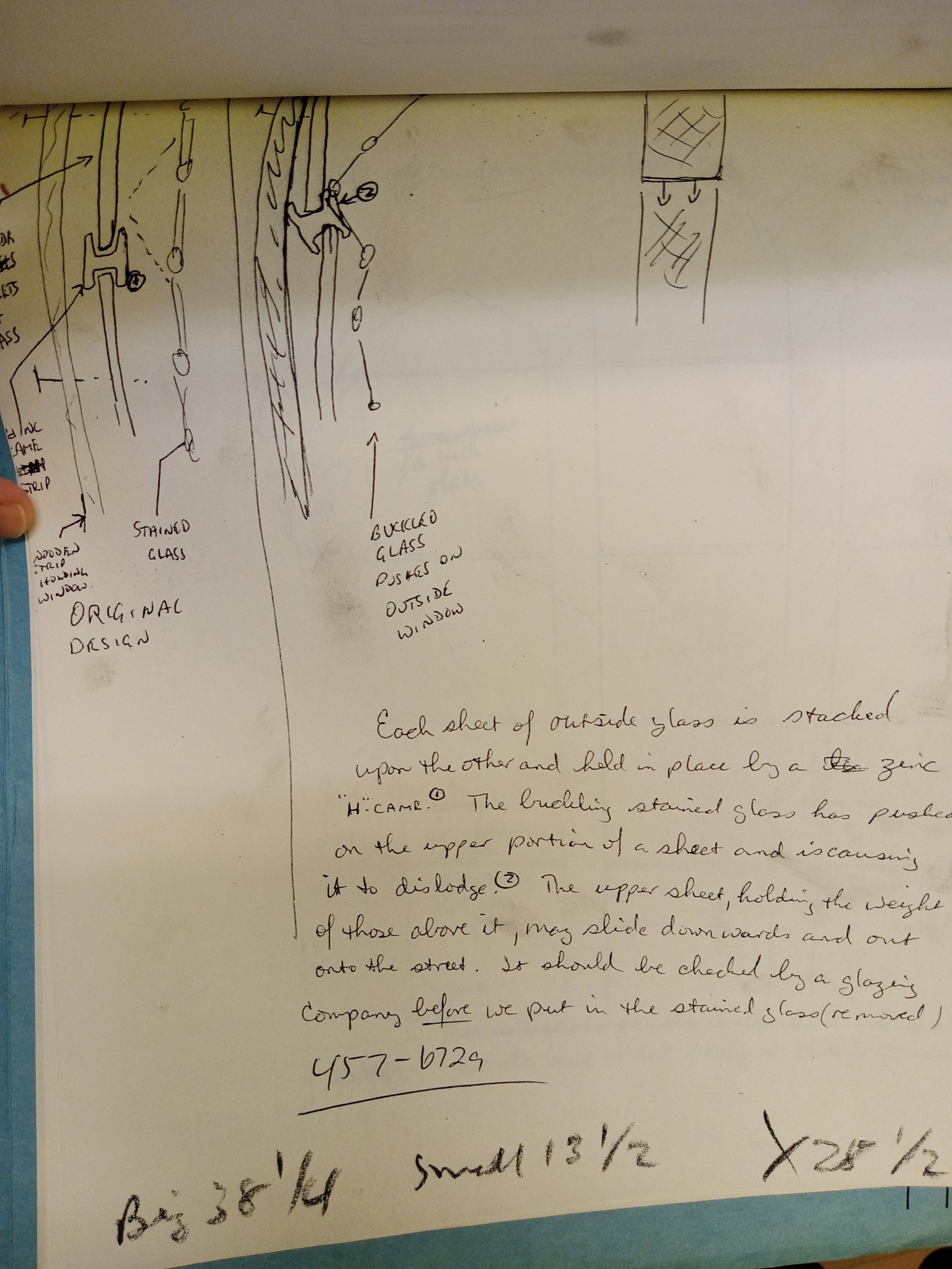

A sketch of the East window (over the altar) from the outside, circa 1987. John Linnell, the chair of the building committee at the time, drew it to accompany a report on the state of the window’s repairs.

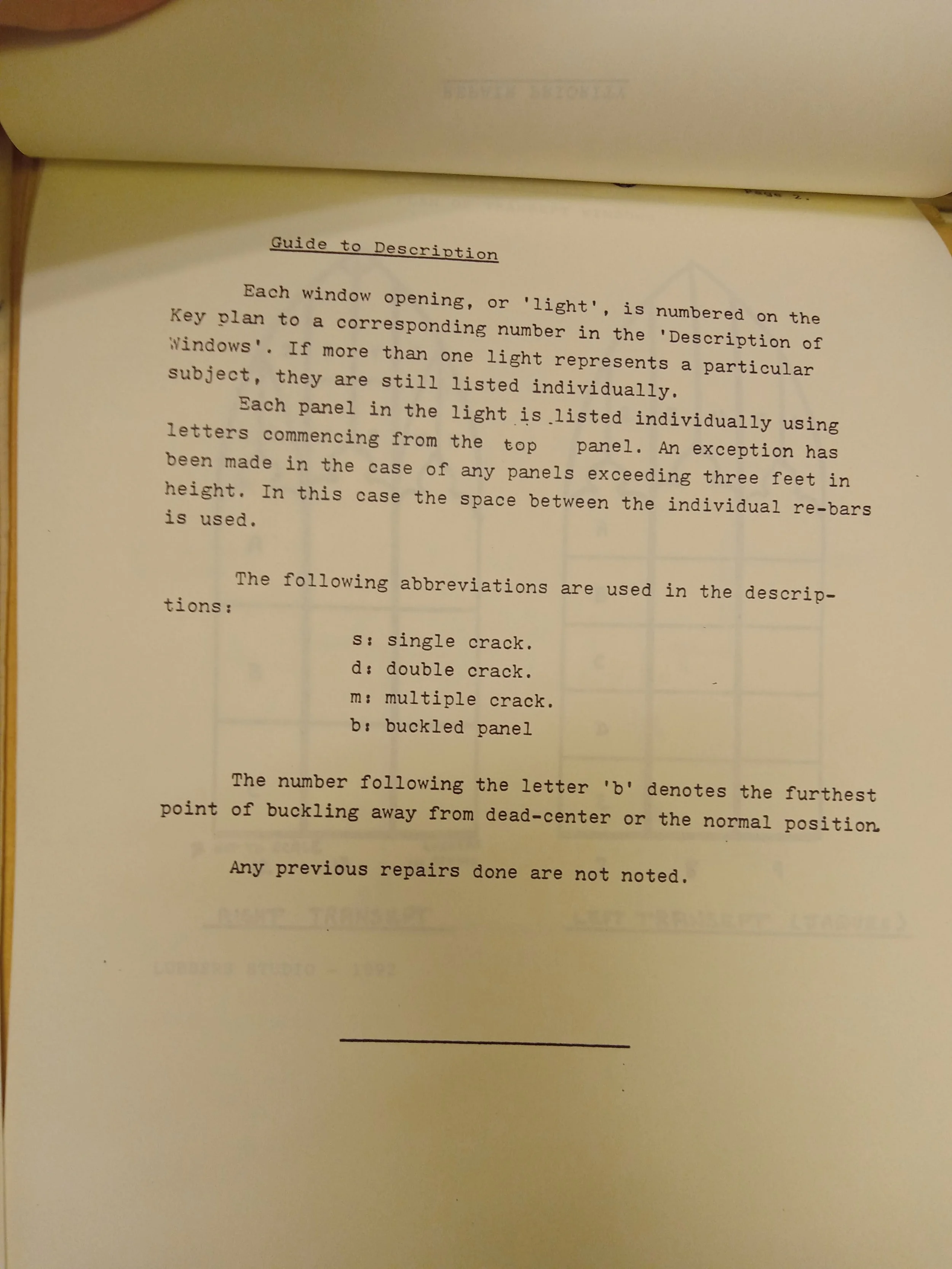

As many of our stained-glass windows were installed in the years immediately before and after WWII, it was only natural that they should have begun needing repairs as they turned 50 in the 1980s and 1990s. In particular, the “Great Lights” – the large windows at the four cardinal points of the building – were beginning to show signs of wear, but thankfully the building committee under chairman John Linnell was on the case. New technology at the end of the twentieth century would allow, supposedly, for more robust protections for these windows, but it was so new that not everyone could agree on whether it was worth the expense.

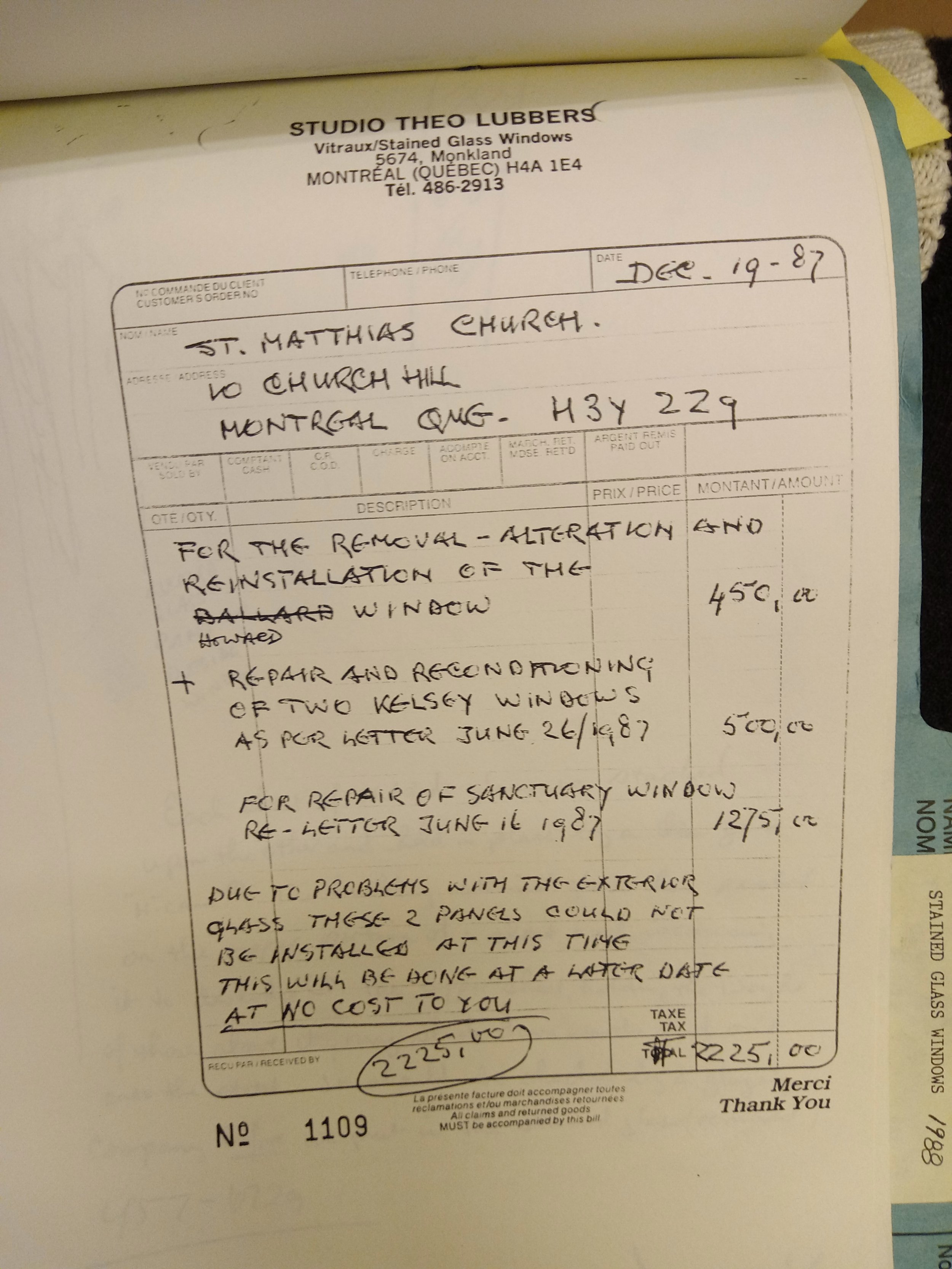

The East Light, above the altar, was having routine maintenance done to some of its lower panels in the autumn of 1987 when the restoration firm, Lubbers Studio, discovered a problem. The double-glazed exterior glass, heavy, ¼-inch glass plates held together by H-shaped strips of zinc, was buckling dangerously – so dangerously that Lubbers’ technicians were uncomfortable putting the stained glass back in. These exterior panes were also cracking; John was told that it might be possible to rotate the panes back to their original configuration by reaching through the window from the inside, but that the danger of shattering was definitely present. Instead, the glazers to whom he reached out suggested rebuilding the outer glass entirely, and replacing it with wire-reinforced glass, which would be “better protection against stone-throwers.” Whatever the decision, the work would not be doable until the spring, and so the church was to be left without lower panels in the East Light for several months. Even cracked and buckling, the outer glass would be protection enough against the weather – after all, that was what it was designed for.

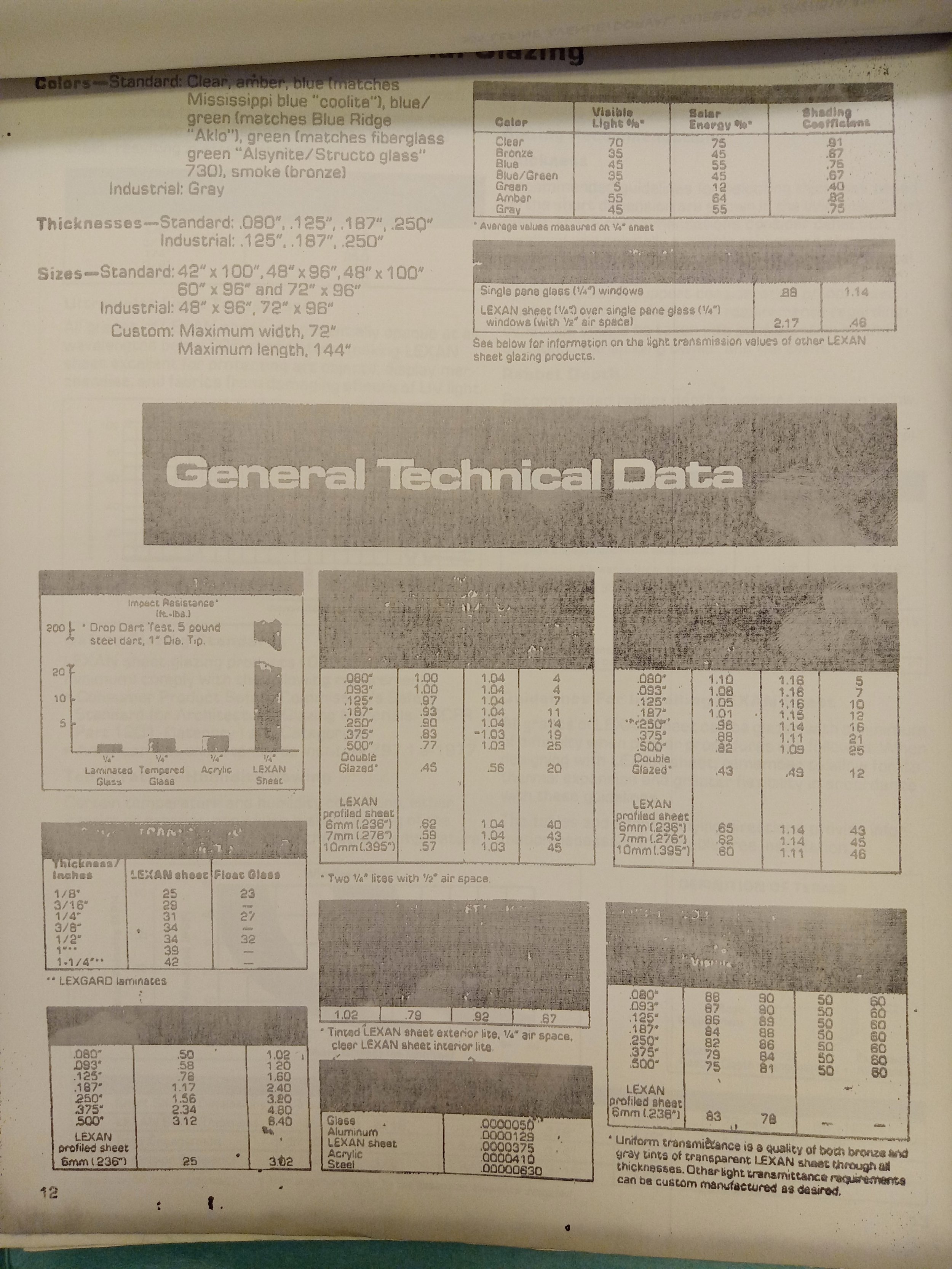

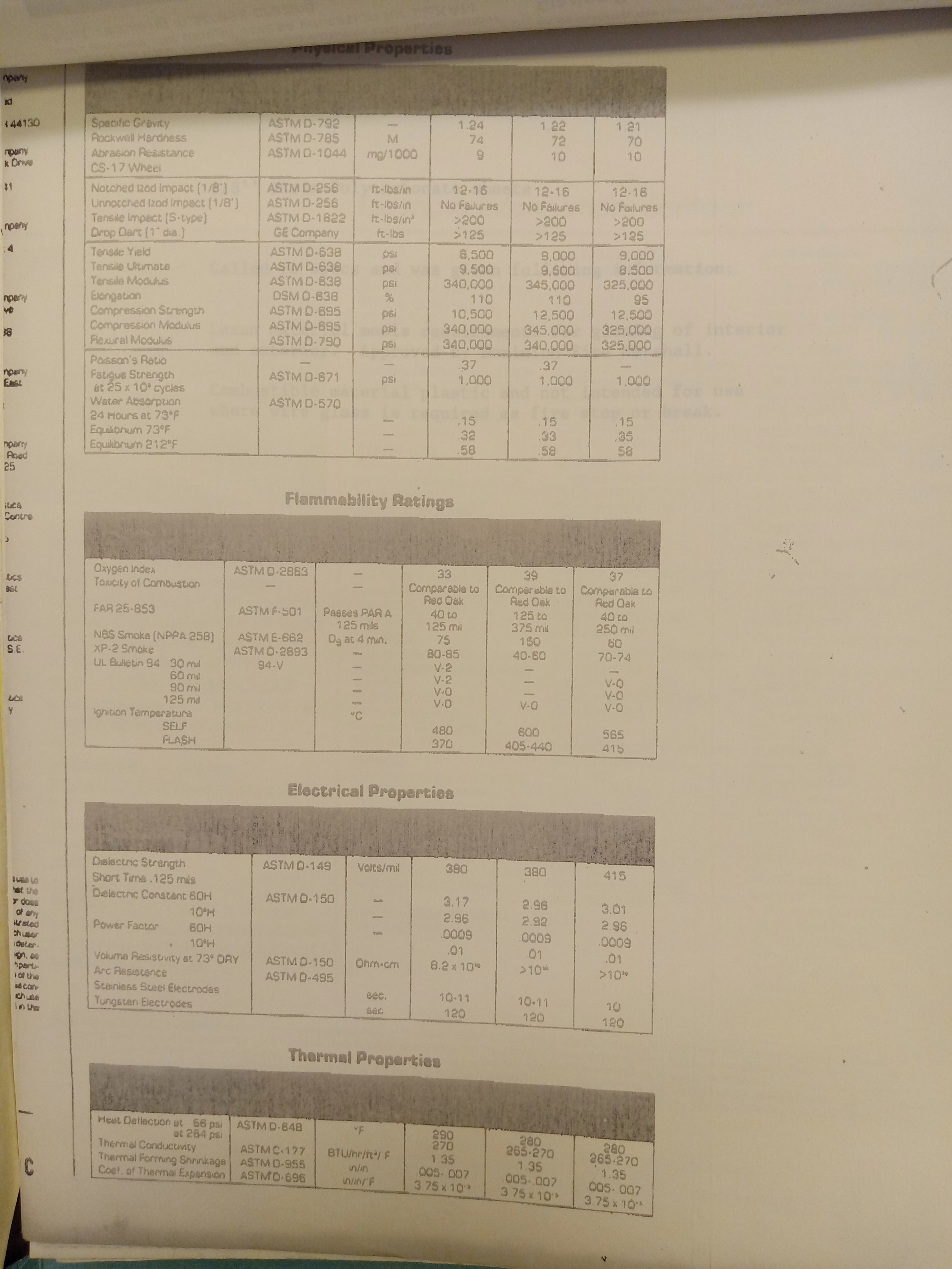

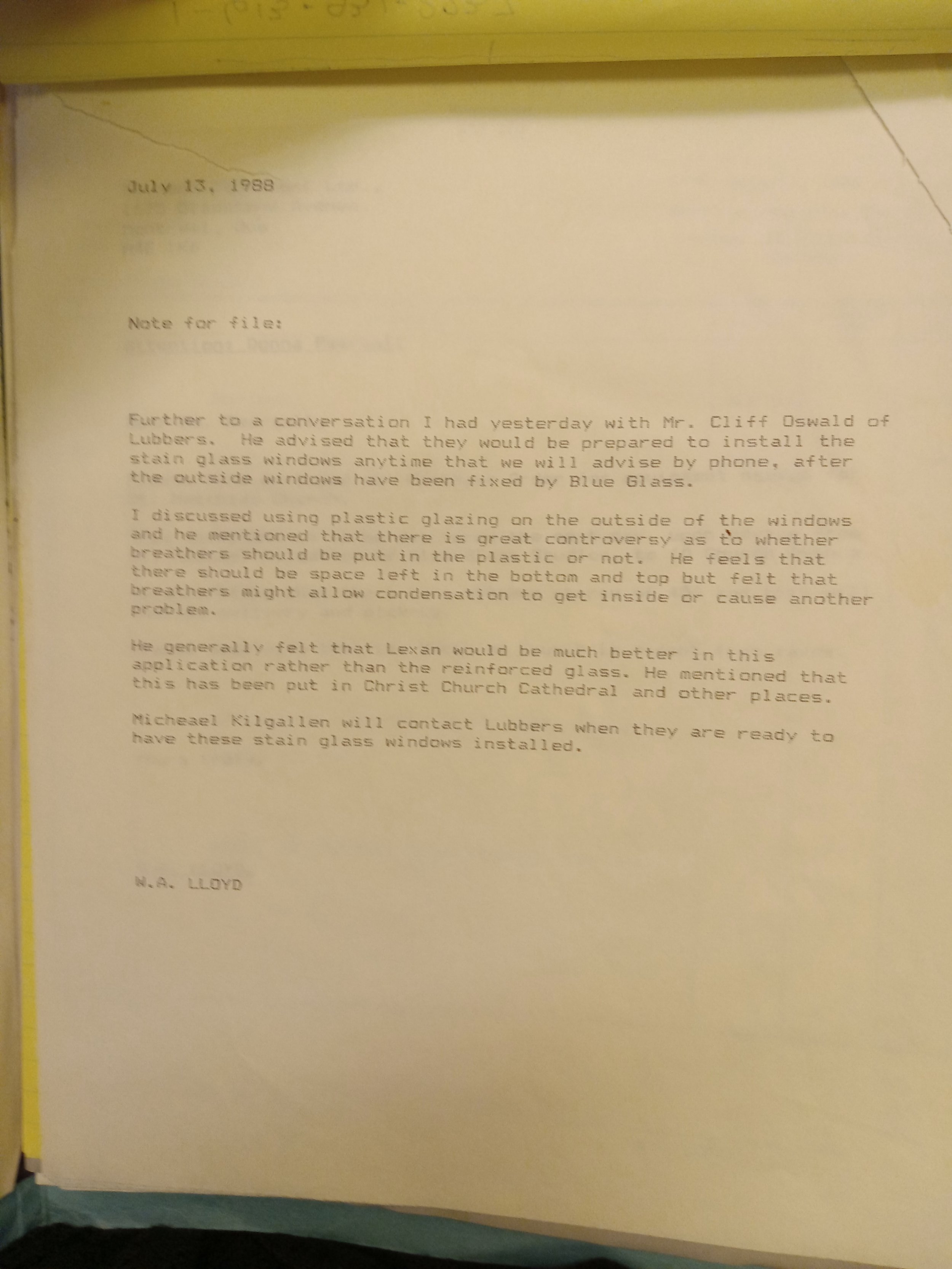

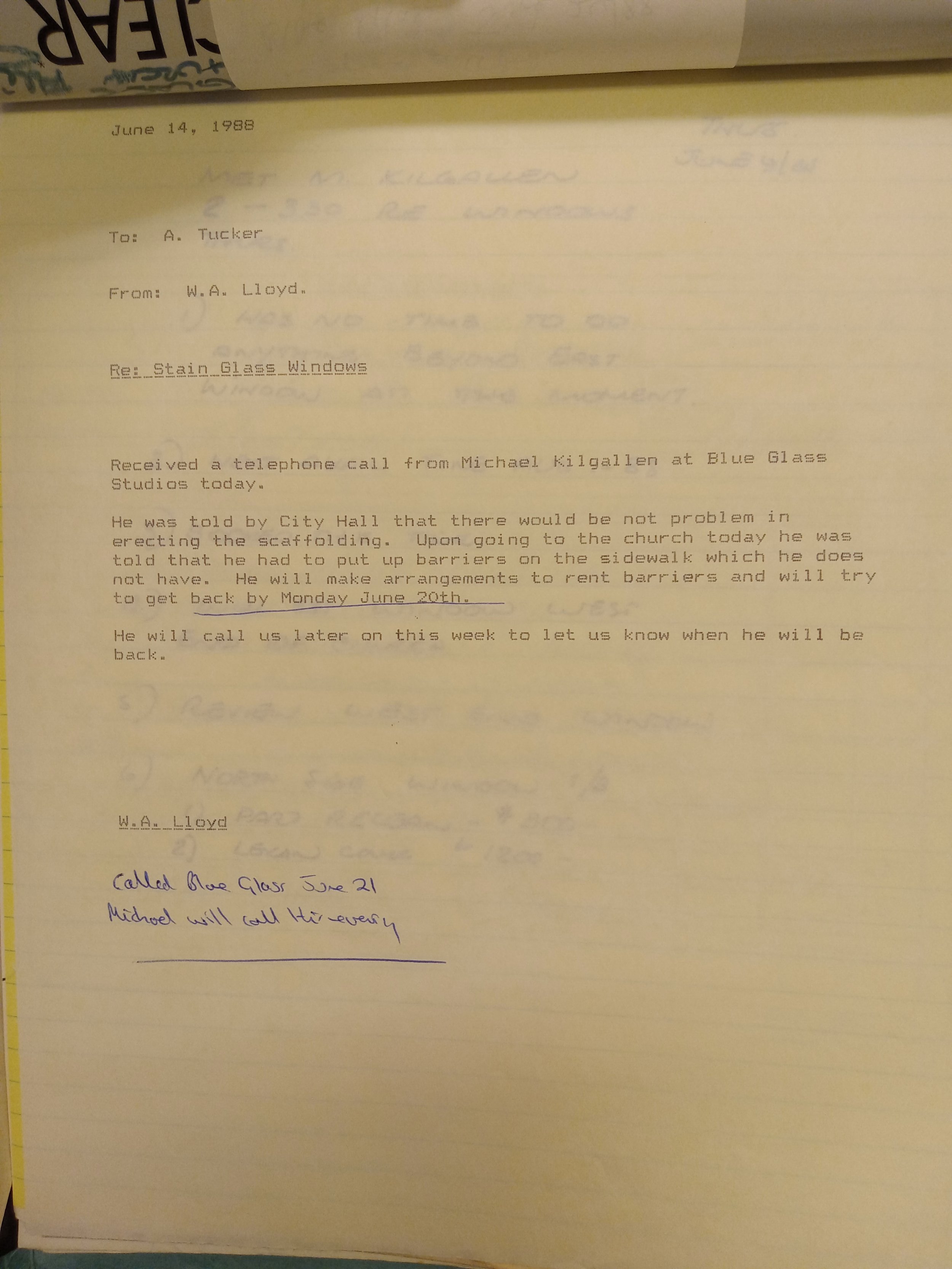

The following spring, John suddenly had more options. Lubbers called him to tell him about a new material, Lexan, that could replace the old double-glazed outer windows. It was being installed at Madison Avenue Baptist in NDG, so Building Committee member Bill Lloyd went out there to chat with the Blue Glass Studios team on the job. Blue Glass happily came to St. Matthias’ to check out the cracked glazing, and declared Lexan would definitely fix the problem. As a polycarbonate, Lexan weighed about 15% of the weight of glass, virtually eliminating the problem of buckling that ¼-inch glass sheets had. It also, by virtue of its composition, could have small holes drilled into it to prevent the kind of humidity buildup in the space between windows that led to leading damage. And, unlike acrylic, which was another not-glass option, Lexan could be UV-treated to prevent yellowing. Bill was sold. Blue Glass were from Cornwall and thought it would be easier to move directly from Madison Avenue Baptist to St. Matthias’, leaving the church only a few weeks to make the decision. Thus followed a flurry of activity, including soliciting Lexan’s technical specs and calling up the insurance company, who assured Bill that except in places where wired glass was required as a fire-break, Lexan would be fine.

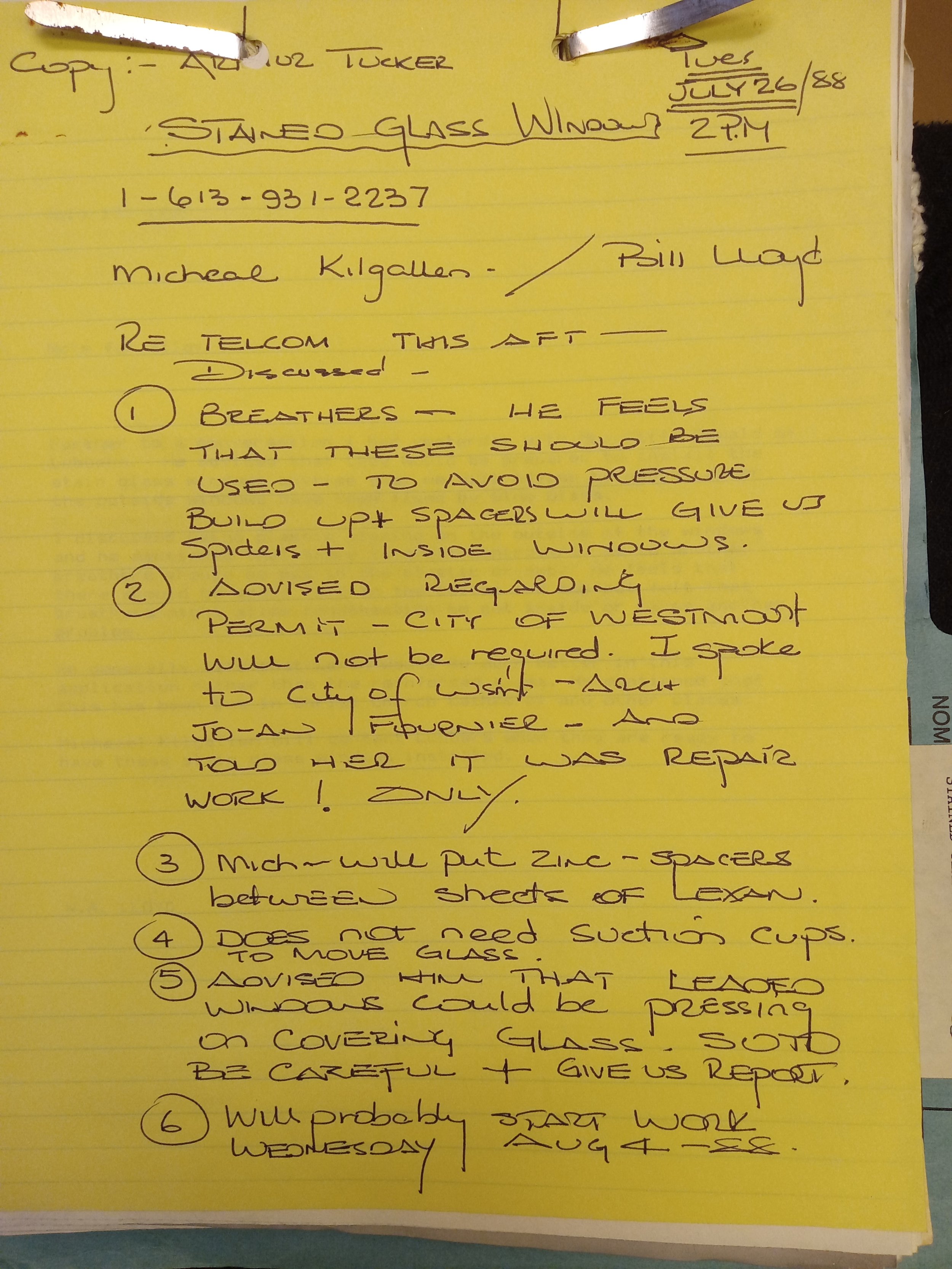

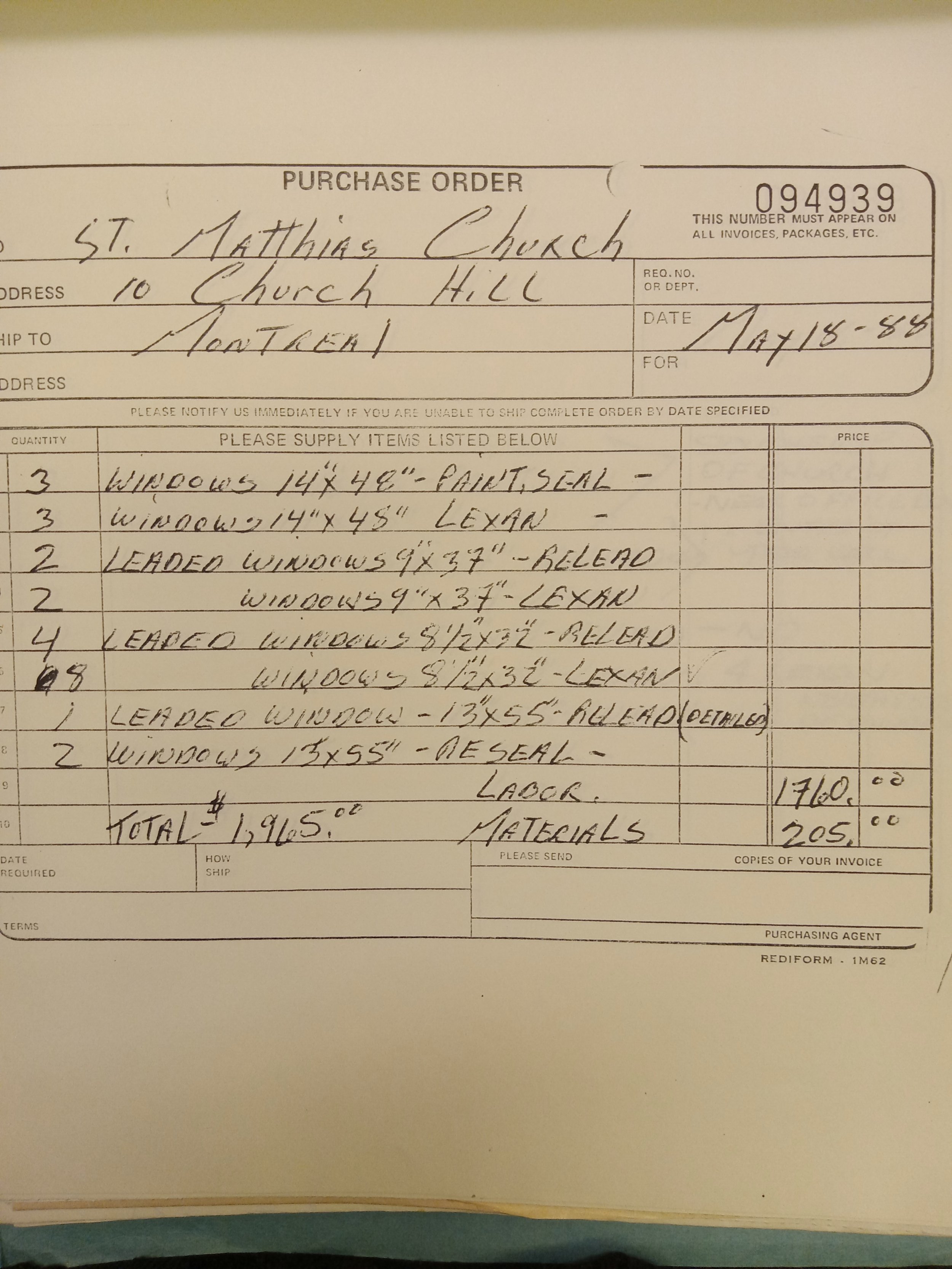

A series of memos from Bill to the Corporation follows the saga of Blue Glass’ interventions: they replaced the East Light glazing with Lexan in June (although they were delayed from their original plan by Westmount permitting issues), and quoted about $2000 (today, $4500) to add Lexan, repair leading, and reseal several other windows. But in July, when Lubbers was getting ready to re-install the East Light’s lower panels, they mentioned to Bill that Lexan was a bit controversial. Those breathing holes left the window vulnerable to condensation, which would damage the leading in the same way that humidity did. As Lexan was considerably more expensive than glass, this was a real consideration. Blue Glass retorted, when Bill asked them, that the pressure buildup without “breathers” was the real problem, and Lubbers’ idea of spacers at top and bottom of a glass window would lead to spider infiltration. It seems that Blue Glass won the day, as they continued window maintenance in August.

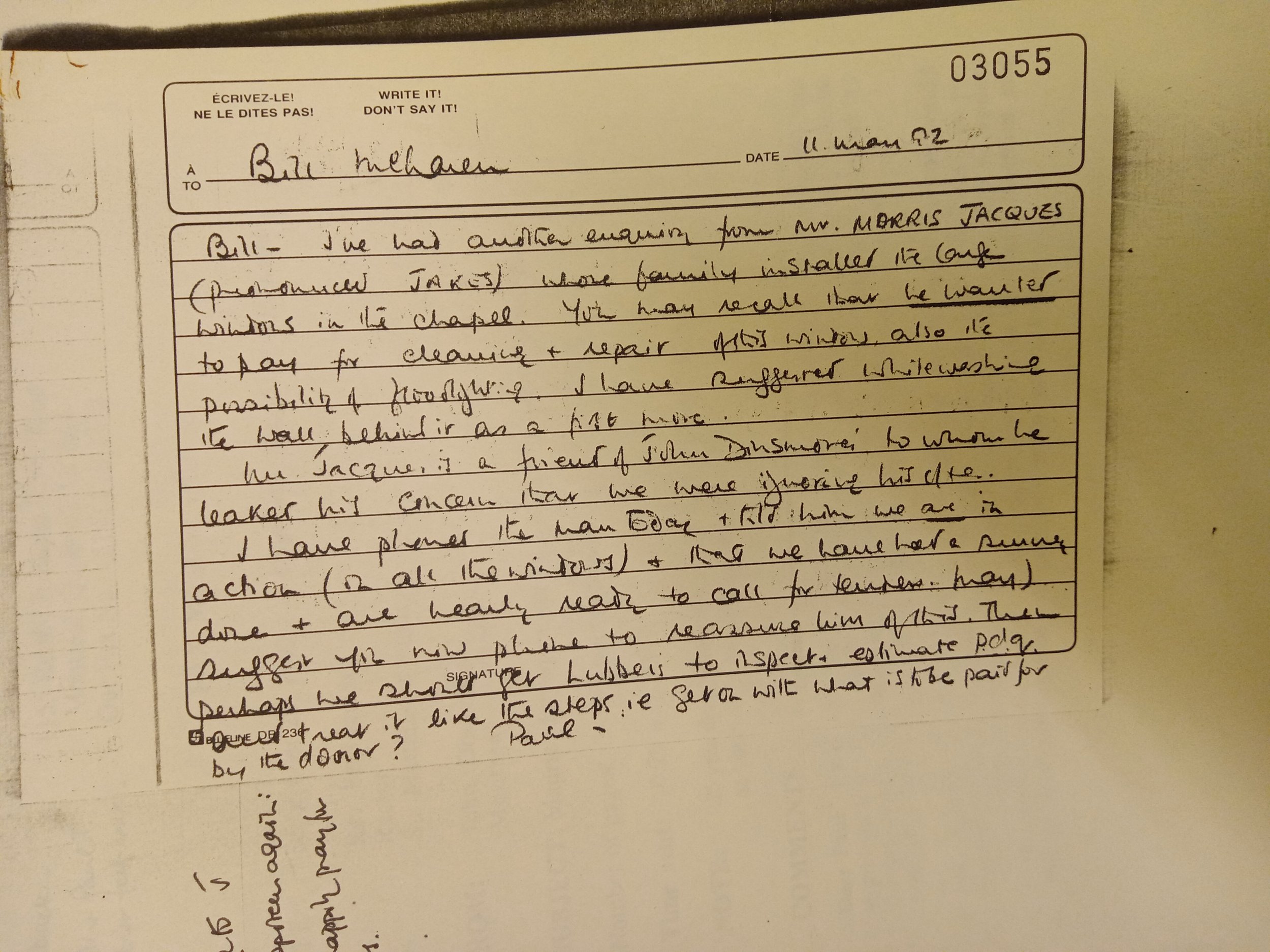

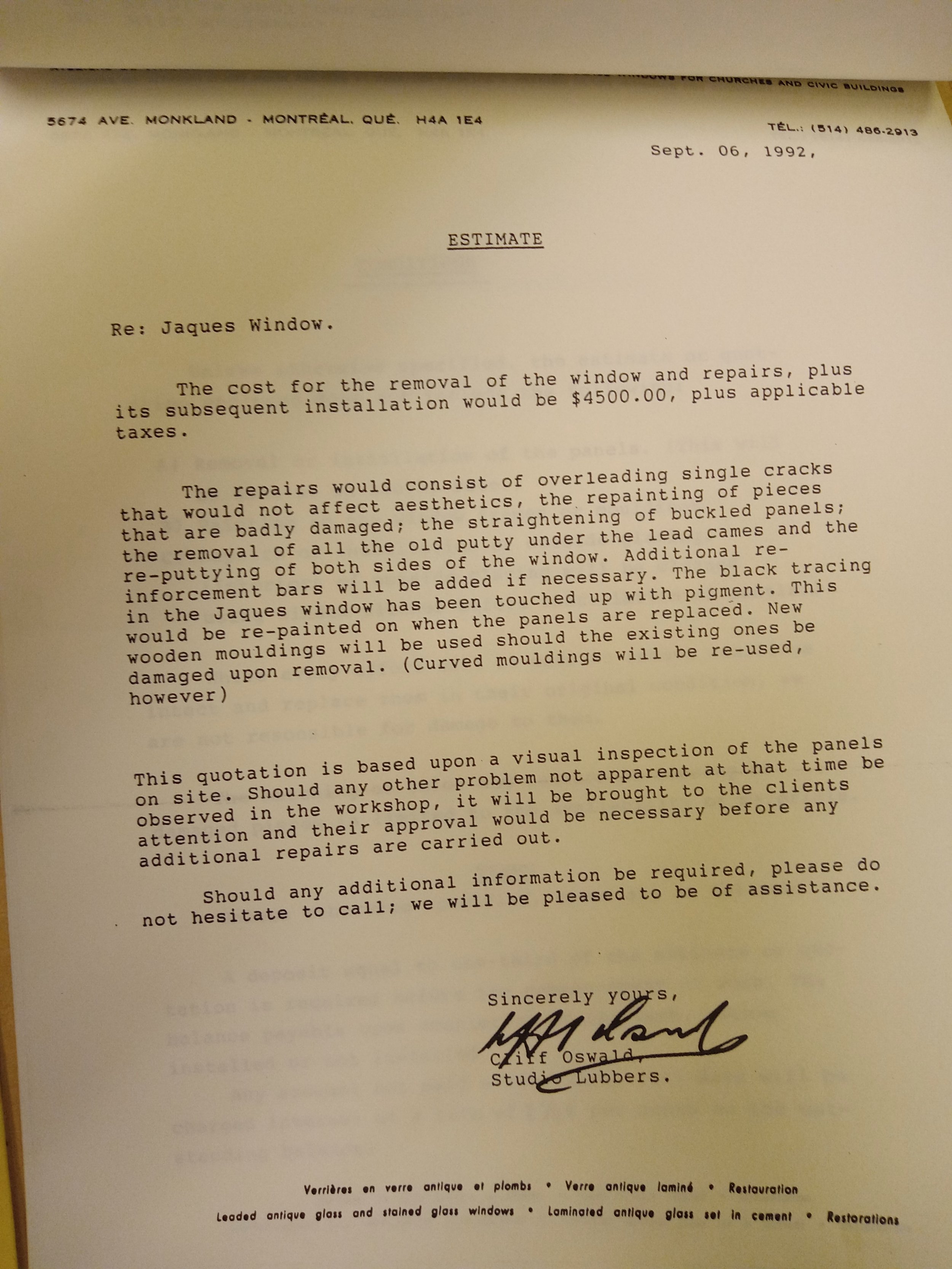

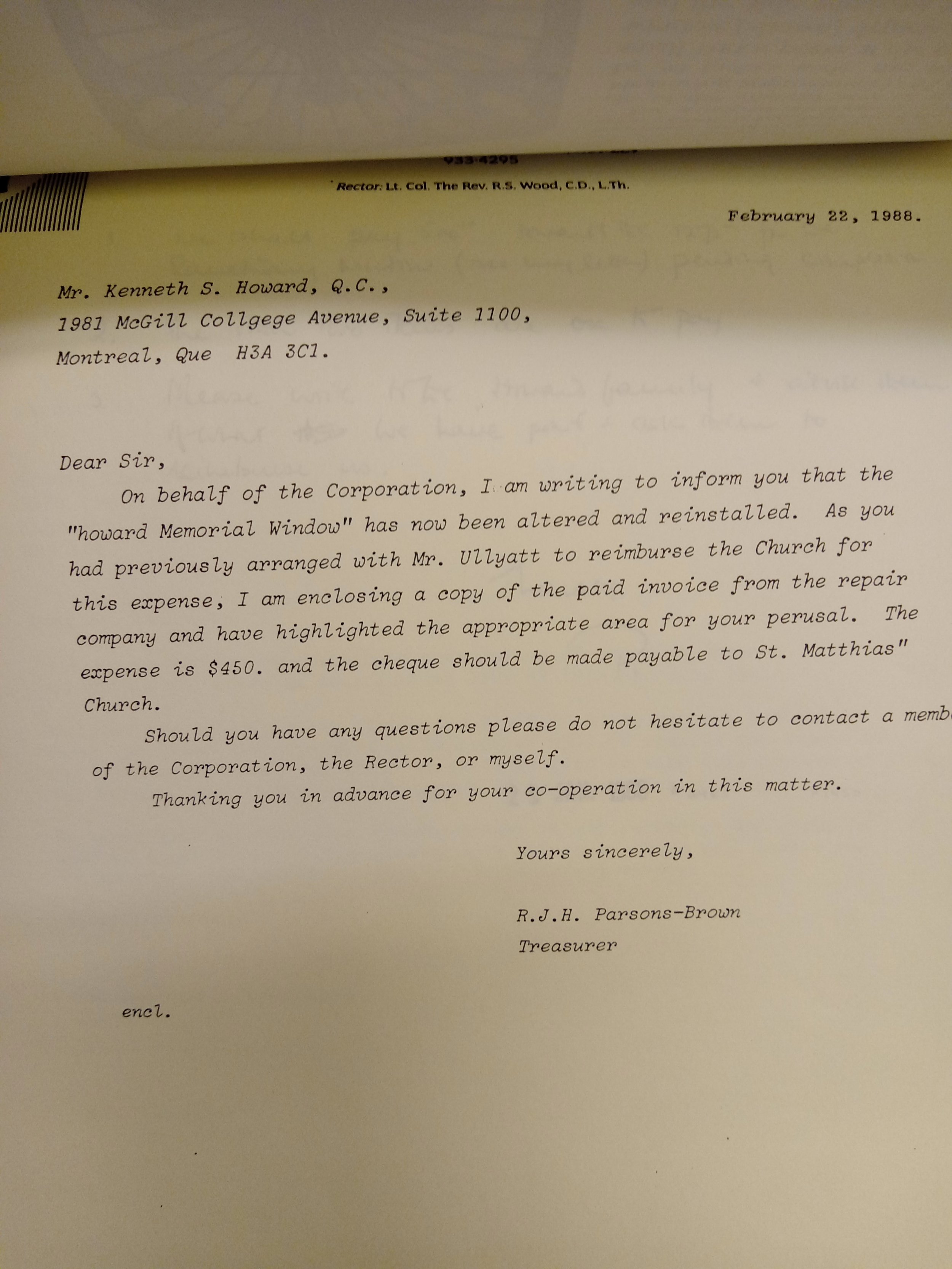

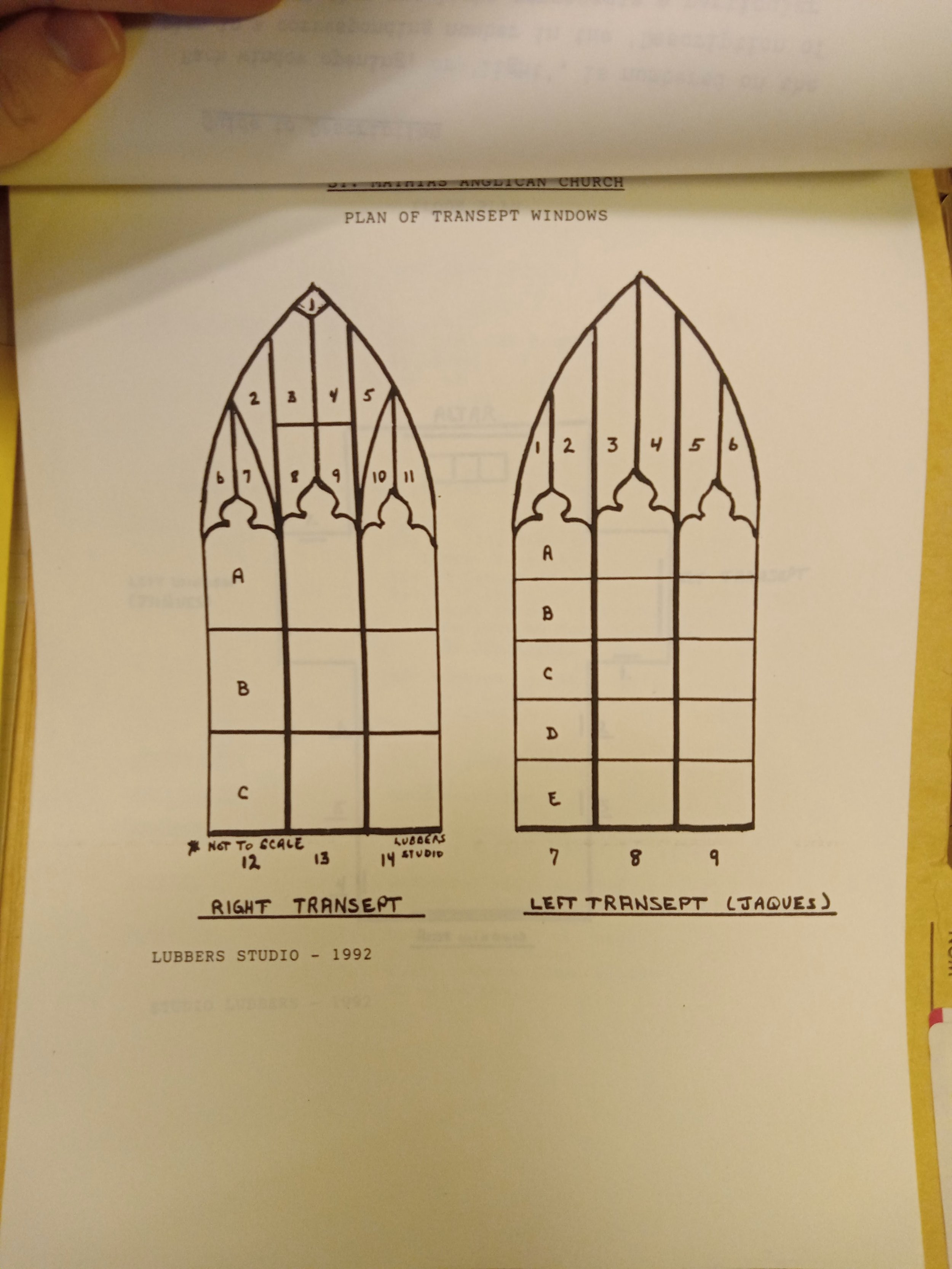

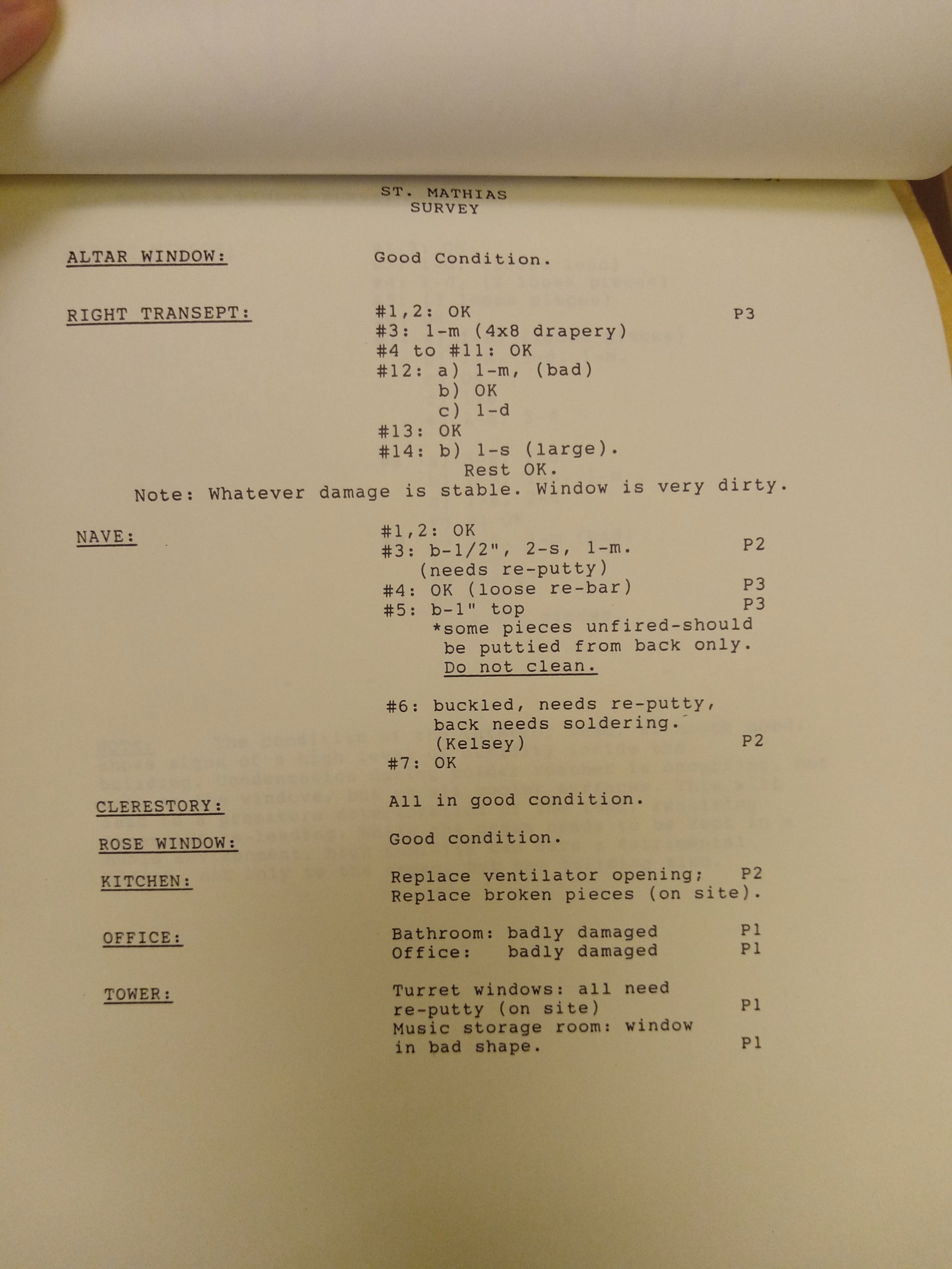

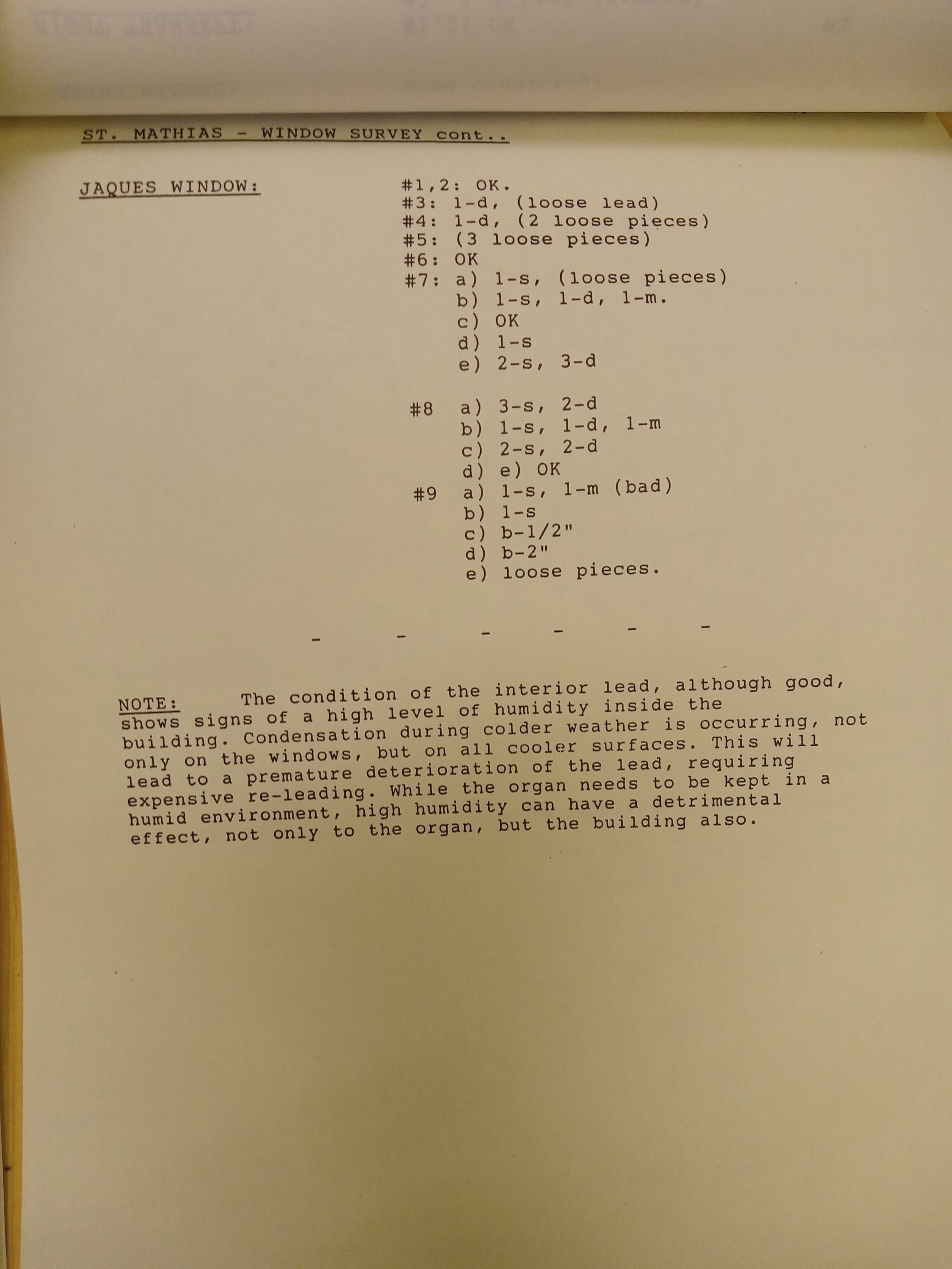

All was quiet on the window front for a few years thereafter – the new Lexan glazing held up, the East Light was finally whole, and the smaller windows that Lubbers and Blue Glass had cleaned and releaded were looking their best. But, as might be expected from such large and complex designs, the North Light (also called the Jacques Window) and the West Light (also called the Scott Window or the Rose Window) were only biding their time. In the early 1990s, both began to exhibit the usual signs of wear, and this time, the Corporation was on the case. Donor relations with both the Jacques and Scott families are the bulk of our archive on these windows, rather than the technical specs from the East Light. The North Light repairs, estimated at $4500 (today, $9000) by Lubbers, involved leading cracks, repainting damaged pieces, re-puttying both sides of the window, and the addition of reinforcement bars. In correspondence lasting nearly three years (discussed in a previous post), the Corporation and the Jacques family figured out a payment plan, and the window was finally repaired in 1993.

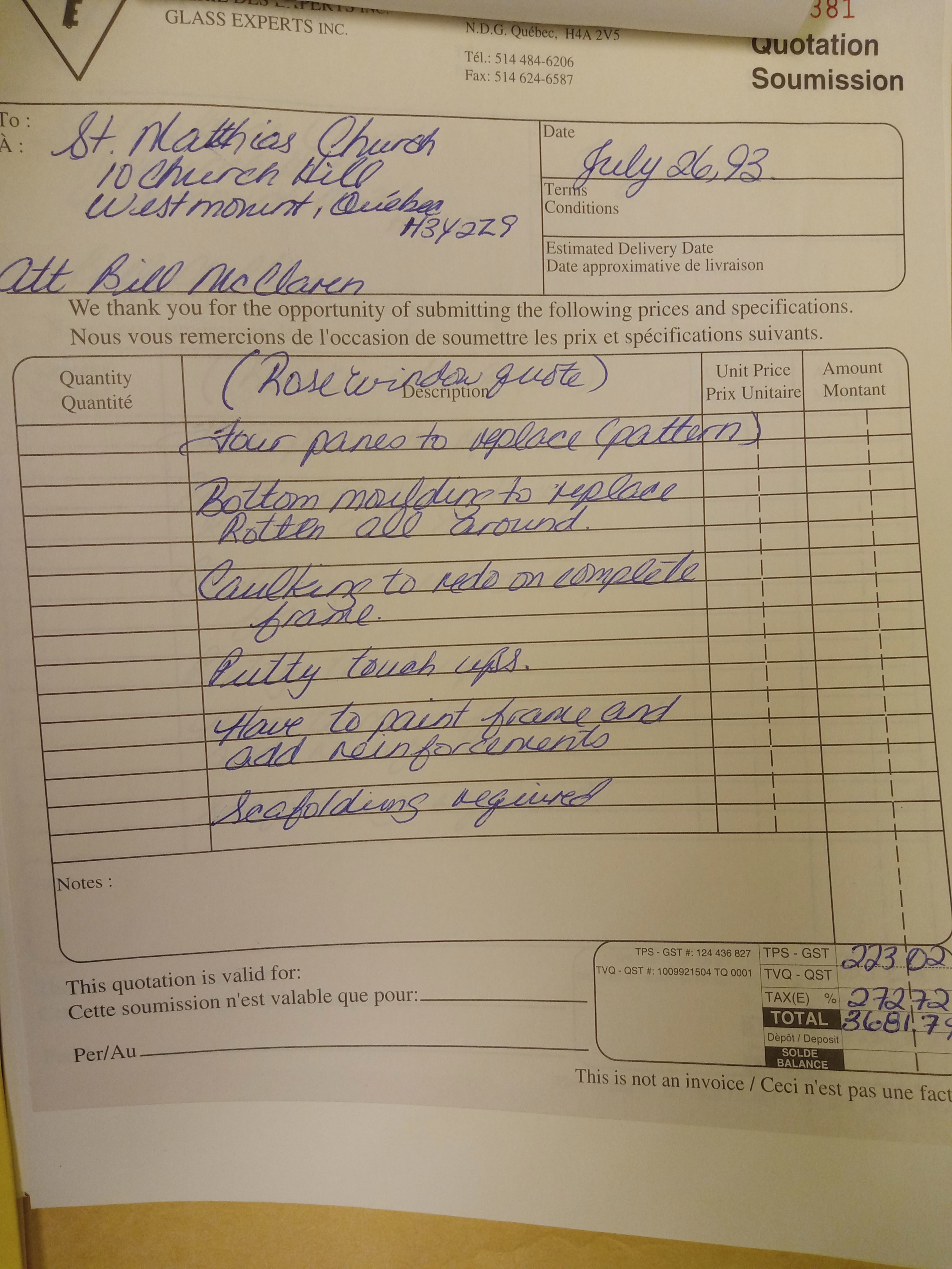

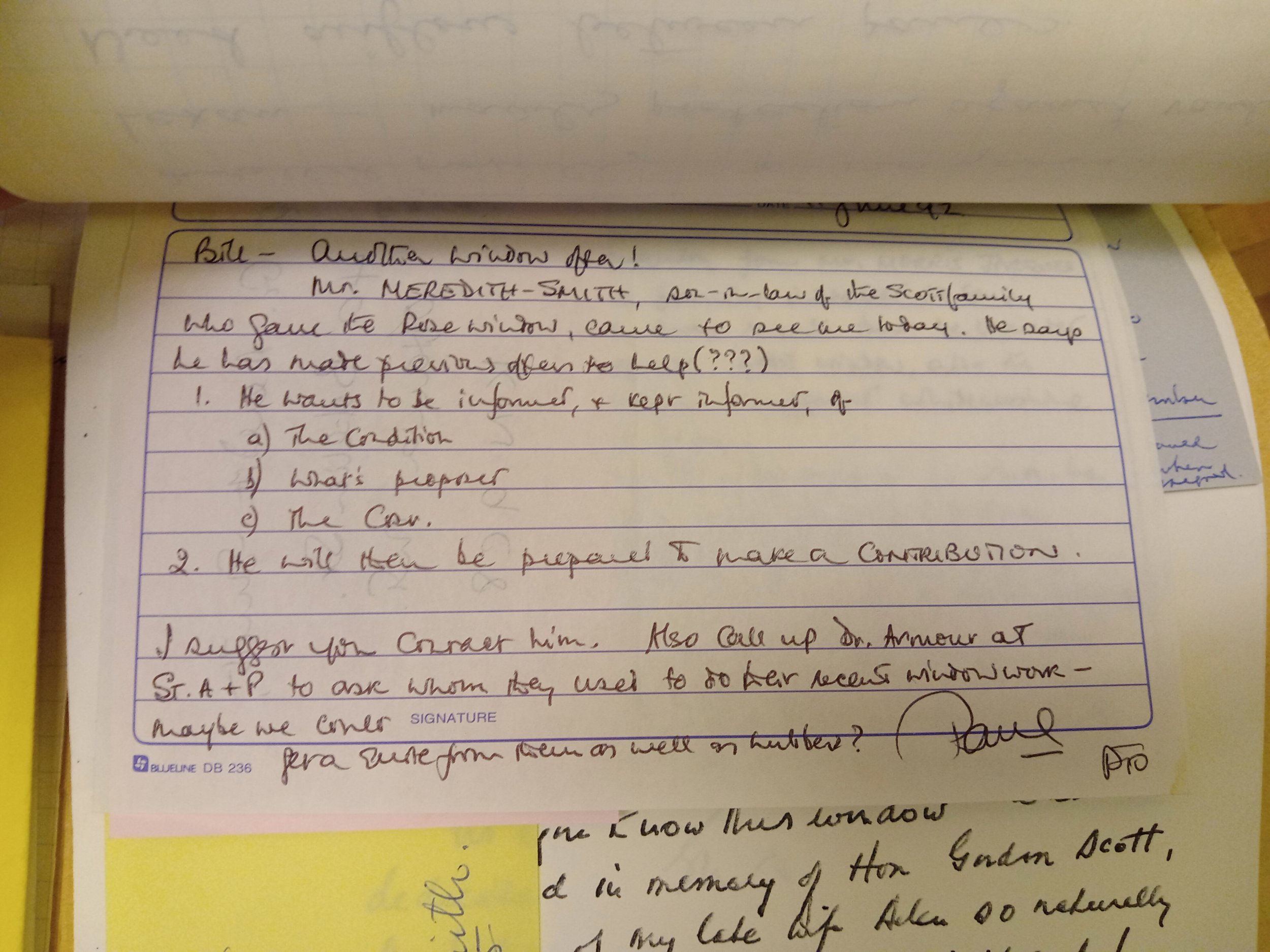

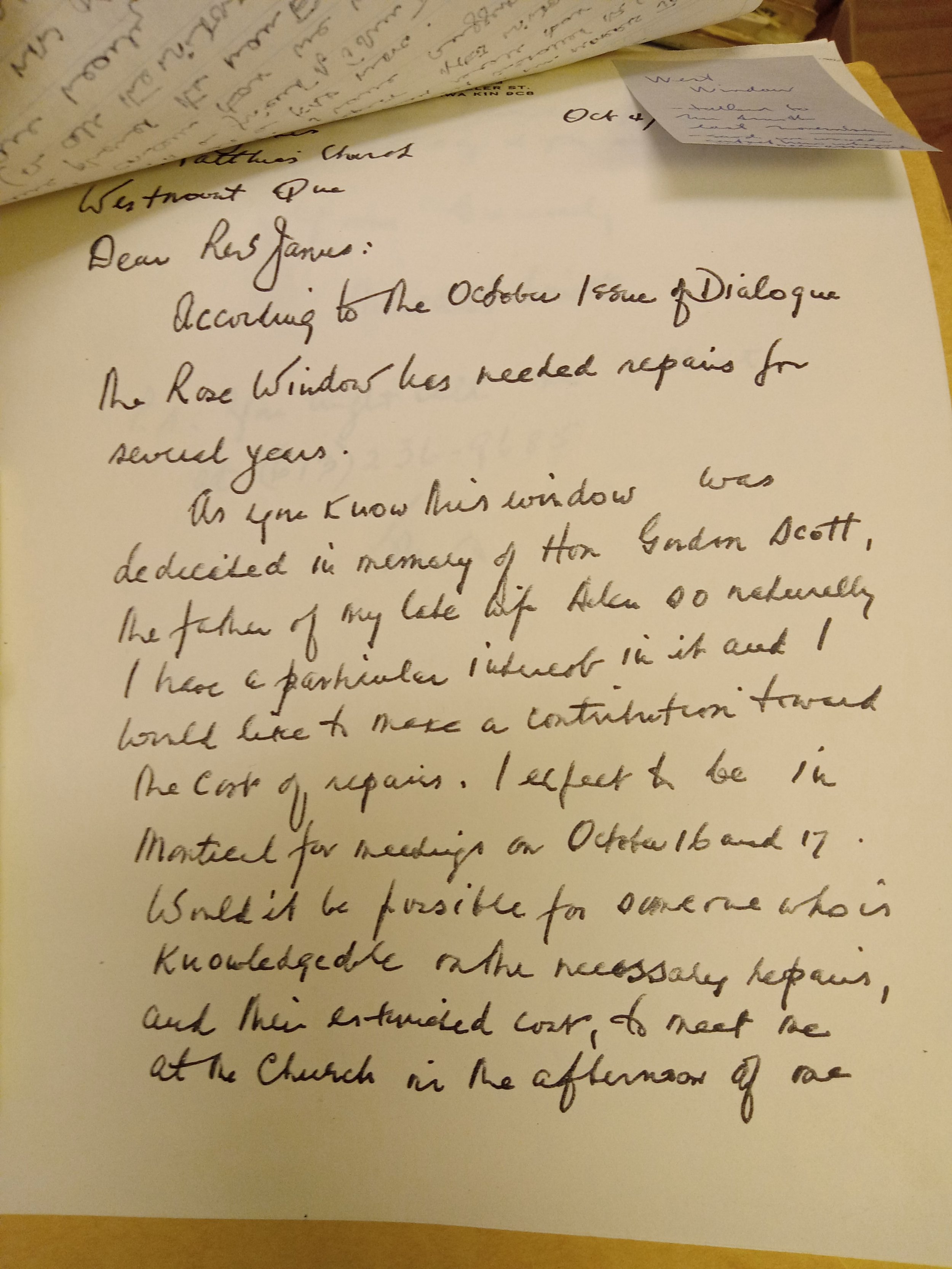

The West Light, estimated at $3700 (today, $6800) for replacement panes, moulding replacement, reinforcements, and putty touch-ups, was discussed in a 1990 issue of Dialogue, the St. Matthias’ newsletter. The publication of this article was met with a letter from a Mr. Meredith-Smith, the son-in-law of Gordon Wallace Scott to whom the window is dedicated. Meredith-Smith indicated that he would like to contribute to the cost of repairs, provided he was able to meet with Lubbers himself, at the church, and hear about the specifics of maintenance. But the letter apparently went unanswered, so, nearly two years later, Meredith-Smith came to visit Rev. Paul James to reaffirm his offer – and his conditions. Warden Bill McLaren, who had managed the North Light’s process, took on the West Light as well. Our archives don’t state whether the repair work was ever completed, nor whether Meredith-Smith was satisfied with the information he was able to obtain.

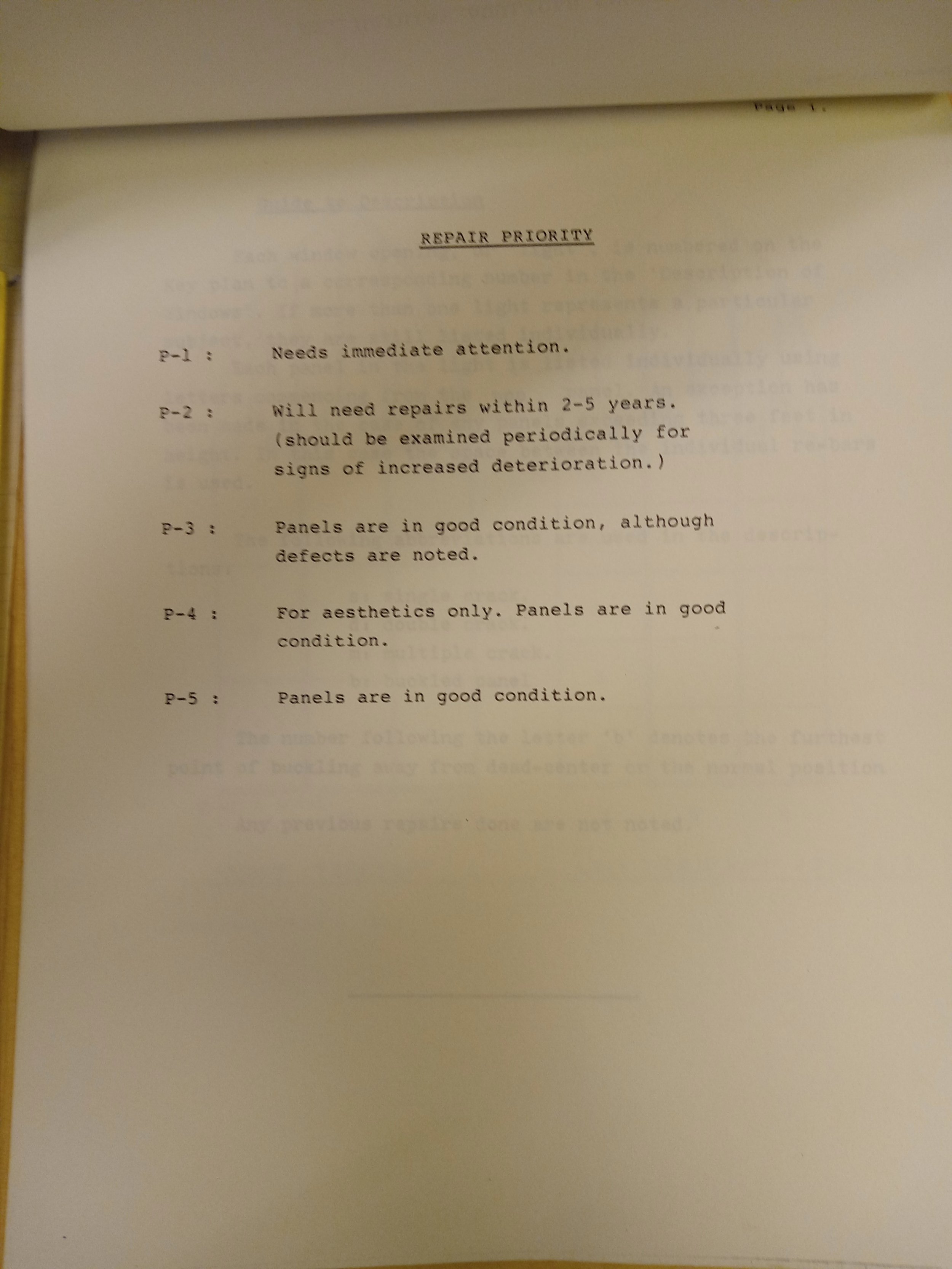

1993 is the last year for which we have documentation on window repairs in the archives, likely due to the gradual transition to digital files that was happening throughout the 1990s. But as a Lubbers Studio report from 1992 makes clear, it may also have been because the windows were for the most part in good condition. The East Light had been repaired in the late 1980s, along with the Howard window, and several others given routine maintenance; the North Light was in the process of being repaired, and we can suppose that the West Light likely was as well. Many of the other lights were in good condition, although Lubbers warned that the humidity necessary for the organ was creating maintenance problems for the windows even before the organ turned 20. As with many aspects of church life, competing needs are difficult to balance! Now, in 2023, we have lost a few panes of Lexan around the building and some of glass in the West Light to heavy winds and other weather, and the South Light’s sheep are so filthy that one might call the Jesus in that window a fairly neglectful shepherd, but otherwise we can be grateful to John Linnell, Bill Llyod, and Bill McLaren for setting us up so well.