July 30th: Reliable Cookery, part two

St. Matthias’ was officially founded as a mission of St. George’s, Place du Canada, in 1873, which means our community is 150 this year! For the next 12 months, we’ll be diving into the archives to shine the spotlight on particularly interesting parts of our history.

Cookbook fundraisers are a tradition that goes back to the 1860s, and were so popular that over the 80 years between then and the 1920s, over 3000 cookbooks were published, mostly by churches, in North America. What began as a genteel way to turn household skills into cold, hard cash has ended up as a rich archive of community history without meaning to, one that focuses our attention on the efforts of women to build that community. Women’s history so rarely appears in our archives, which are centred on the “business” of St. Matthias’ as conducted by the men of the parish. What might we find out about the historical forces shaping Matthian women in the 1910s by diving into their Cookery Book’s pages?

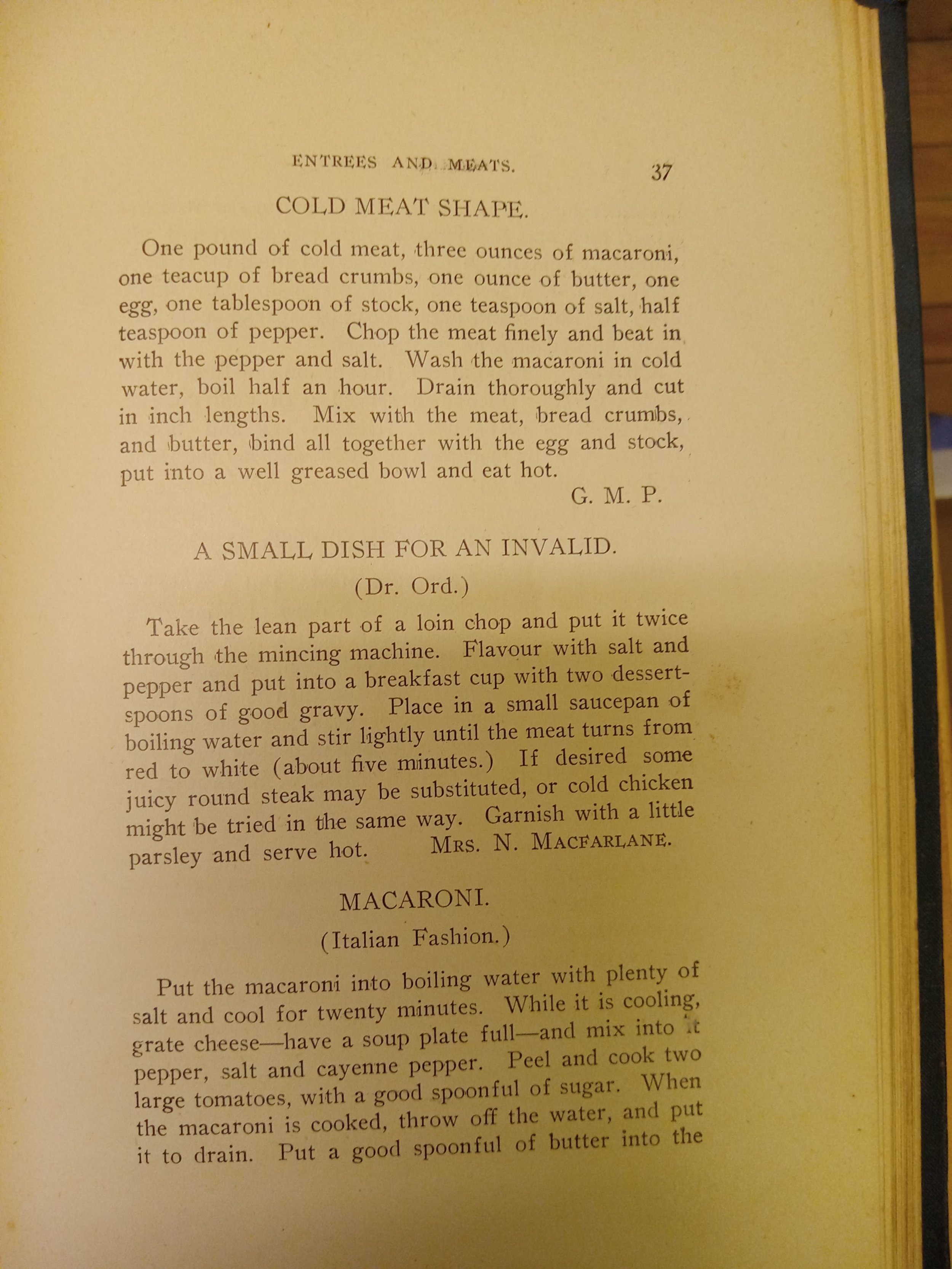

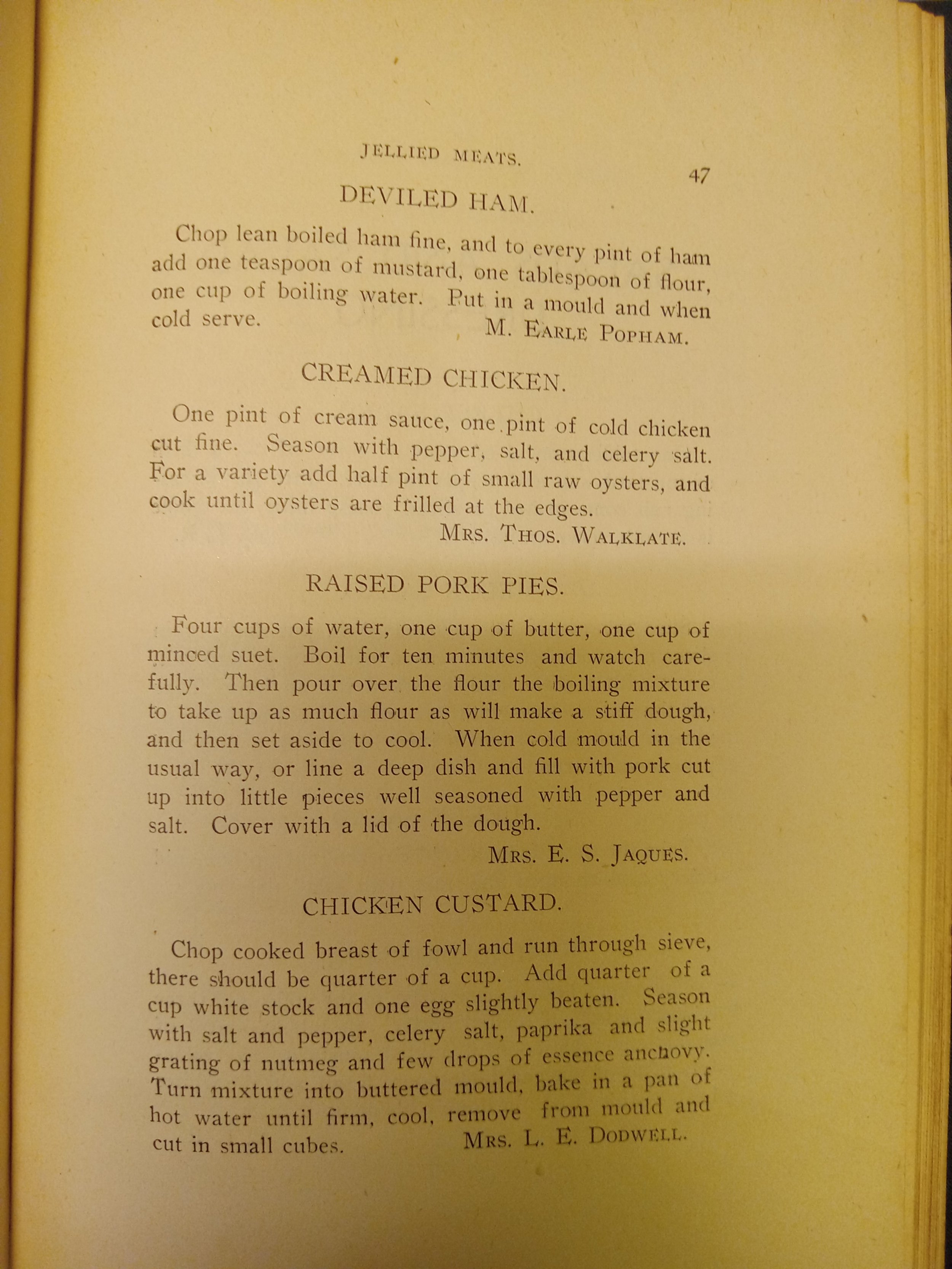

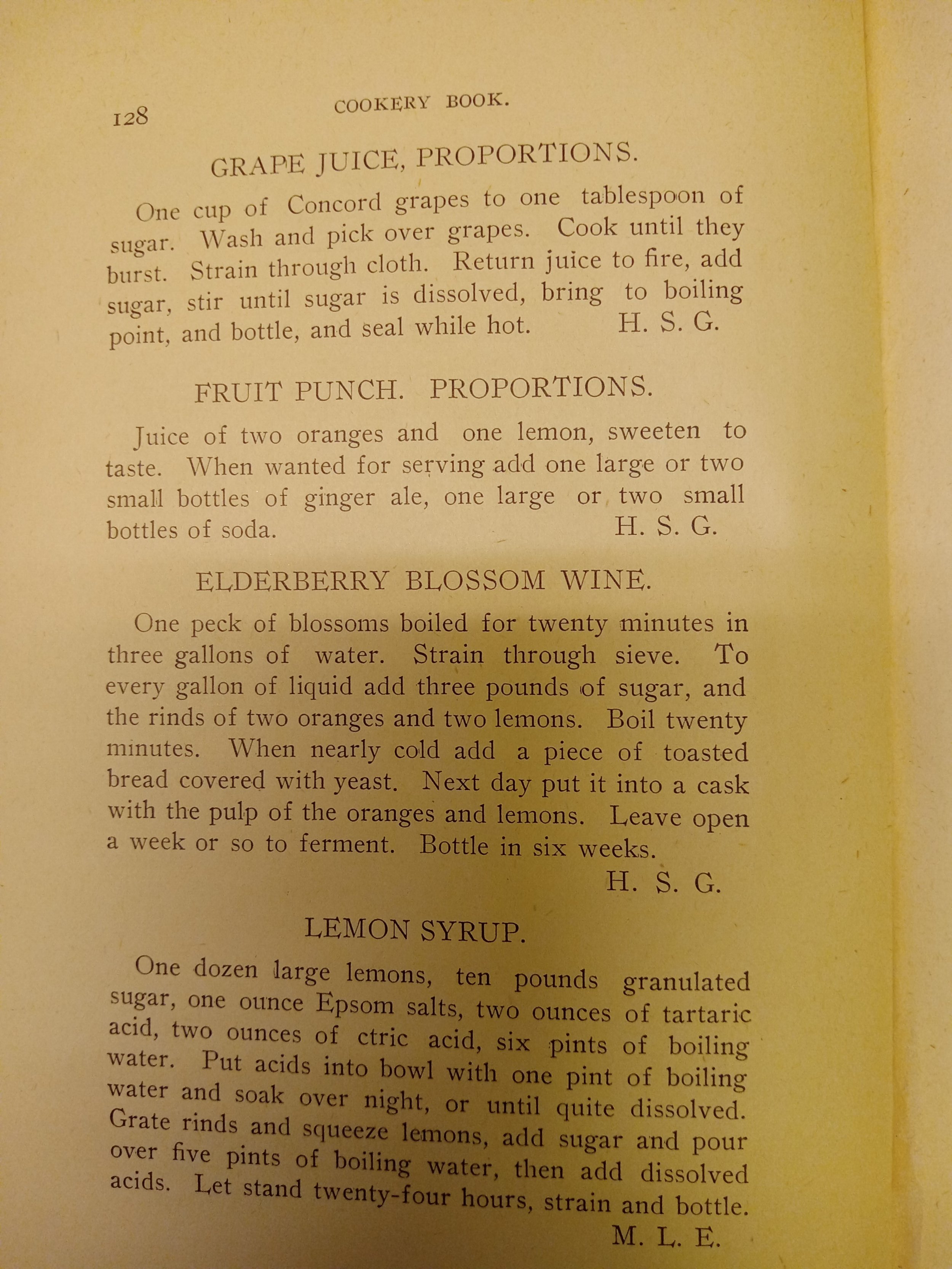

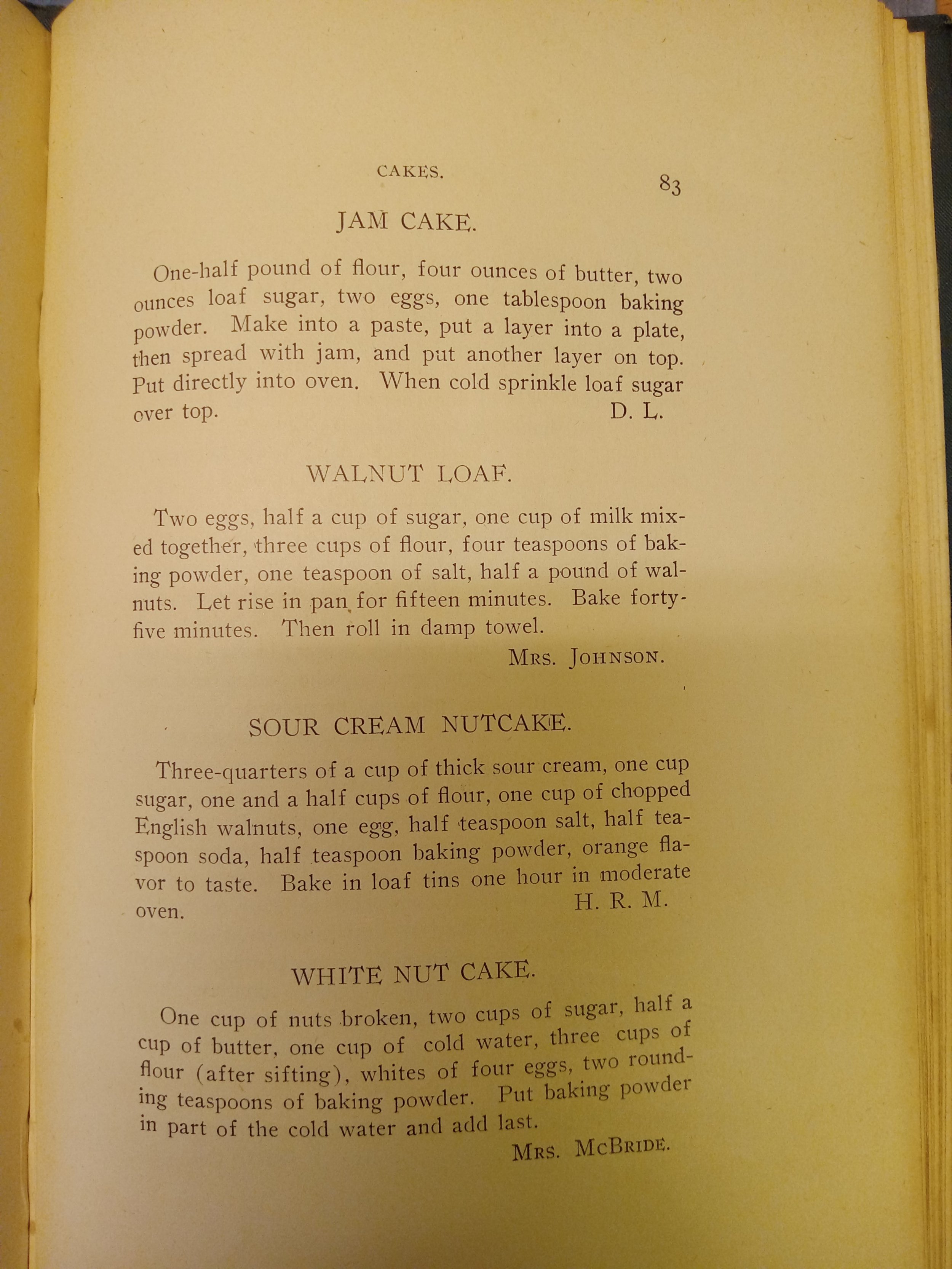

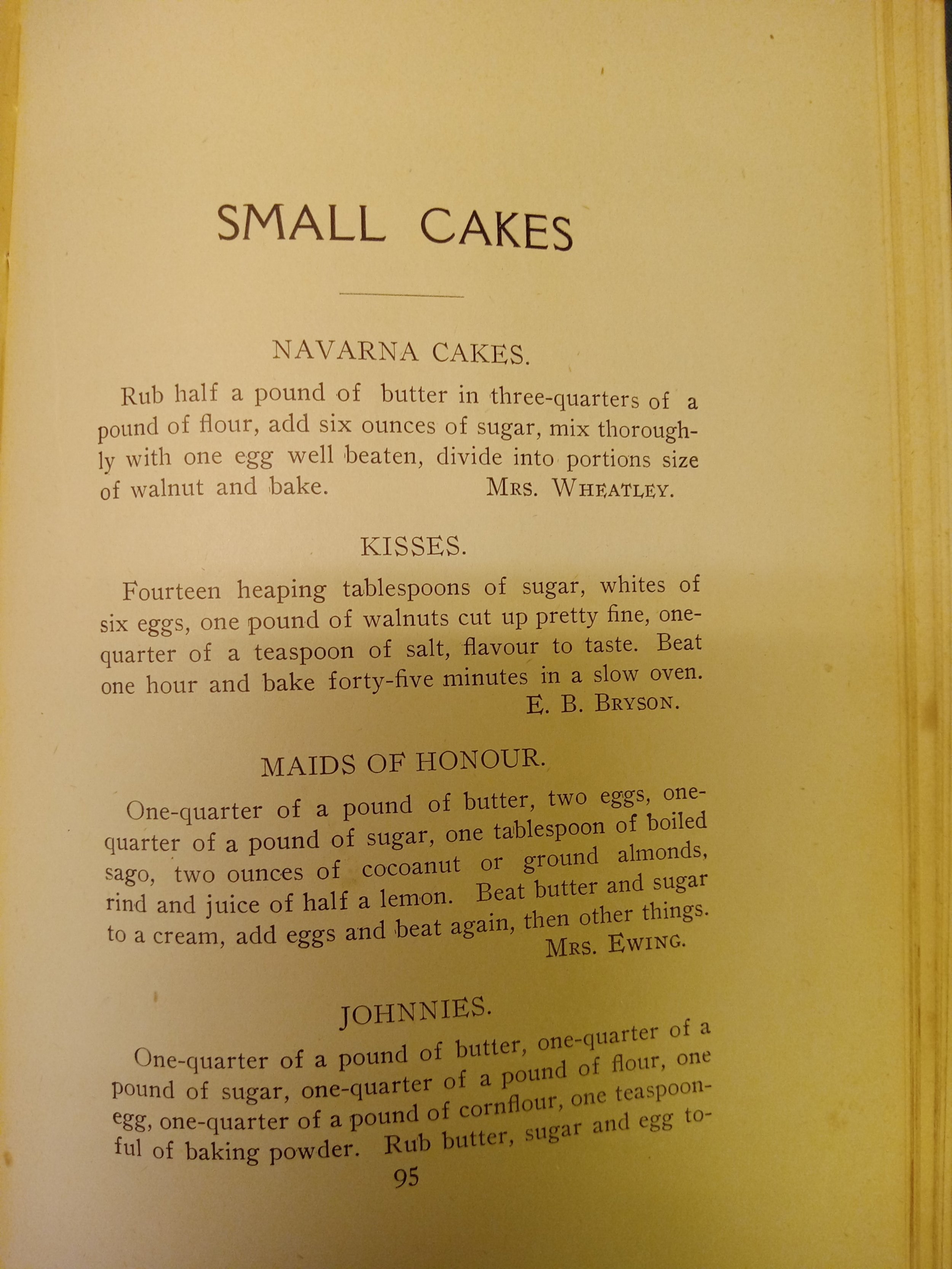

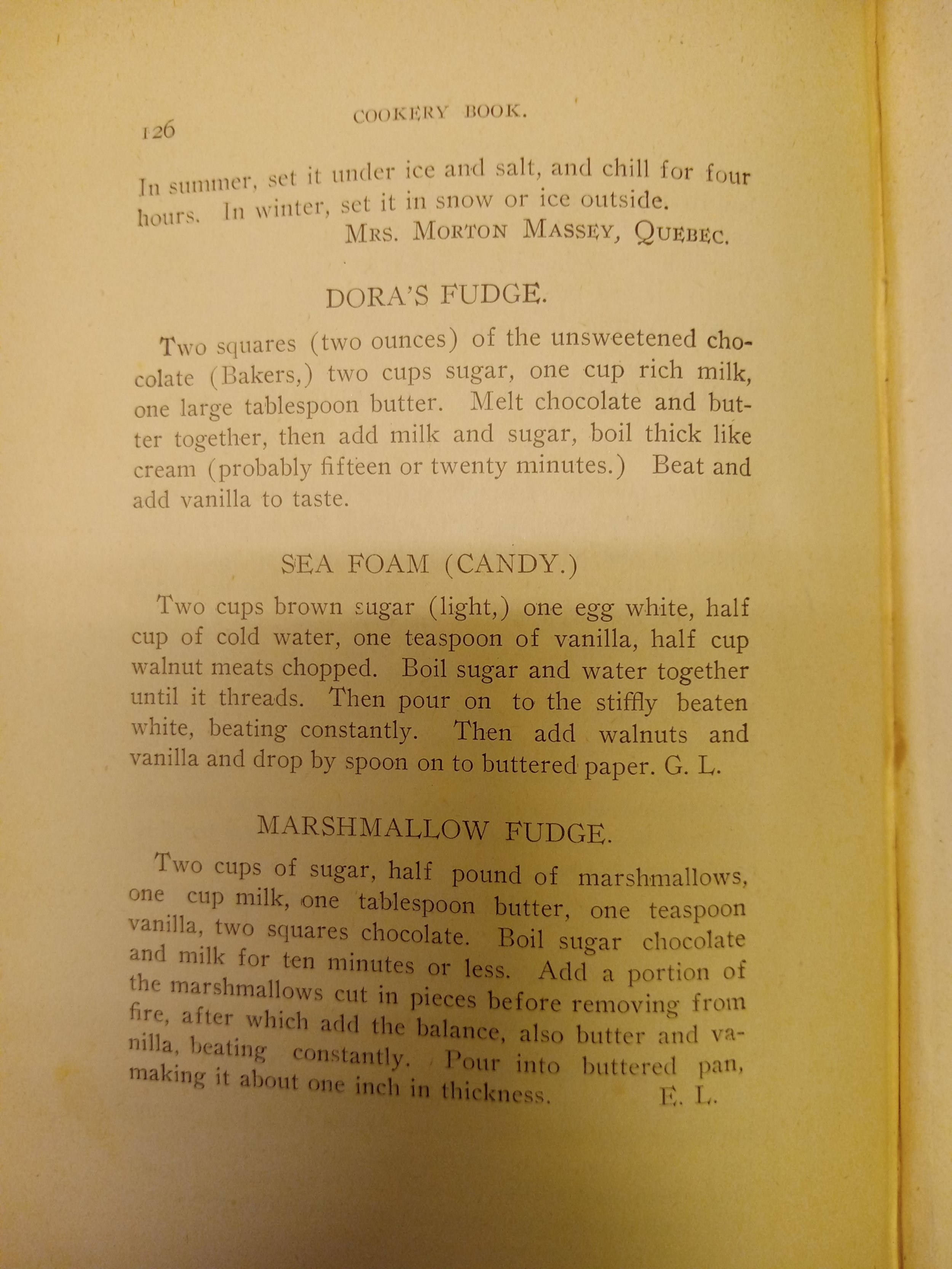

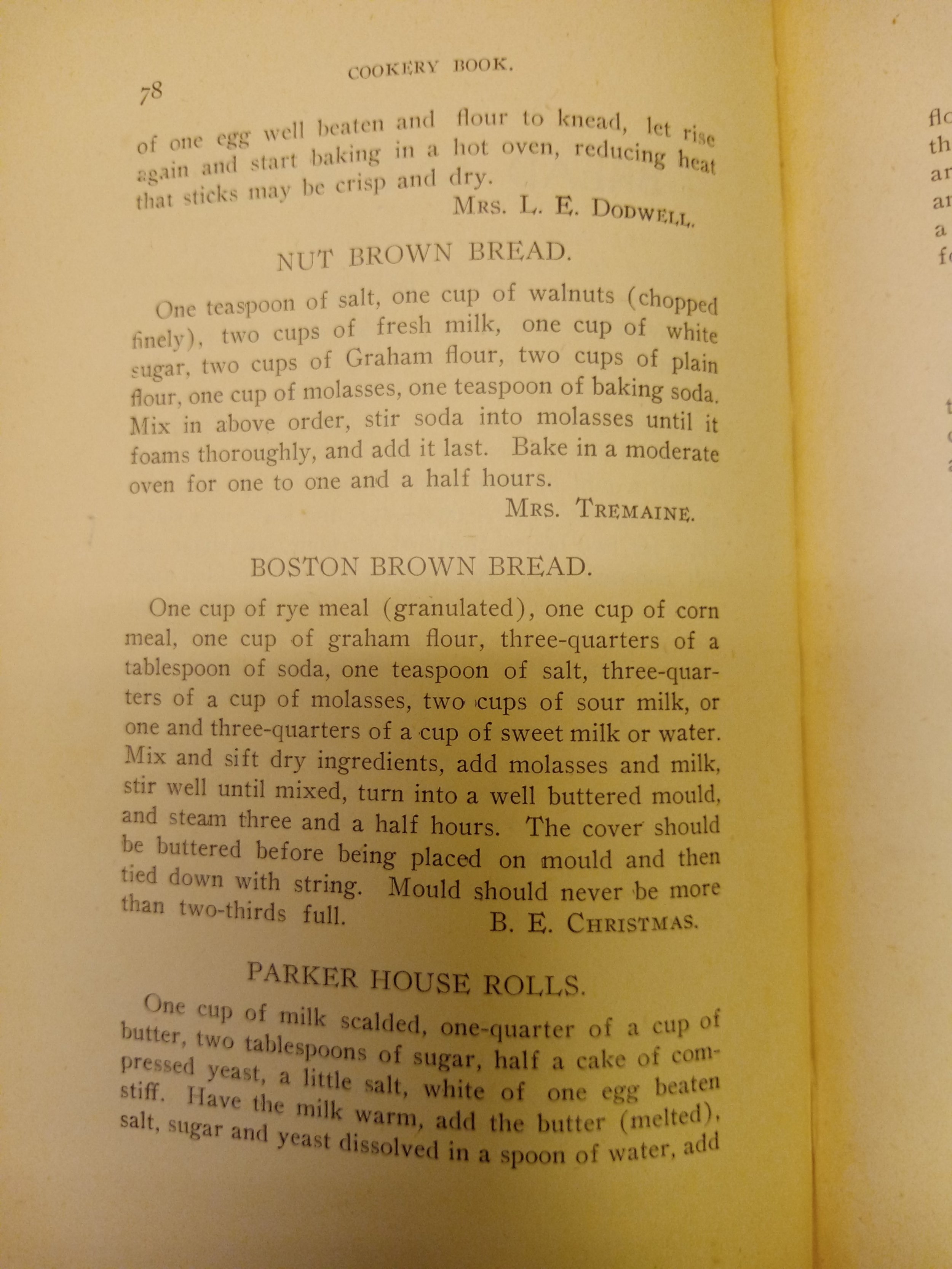

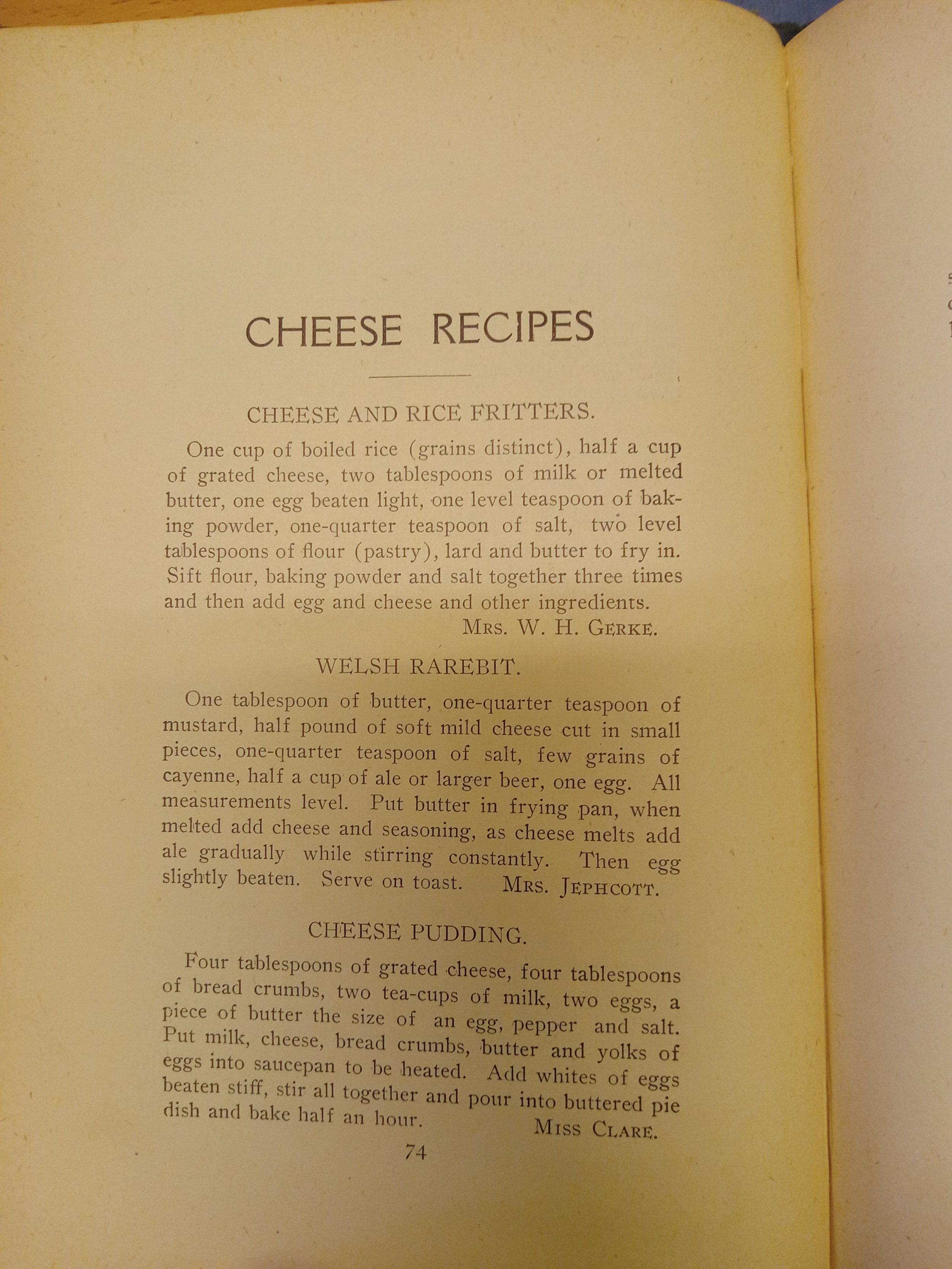

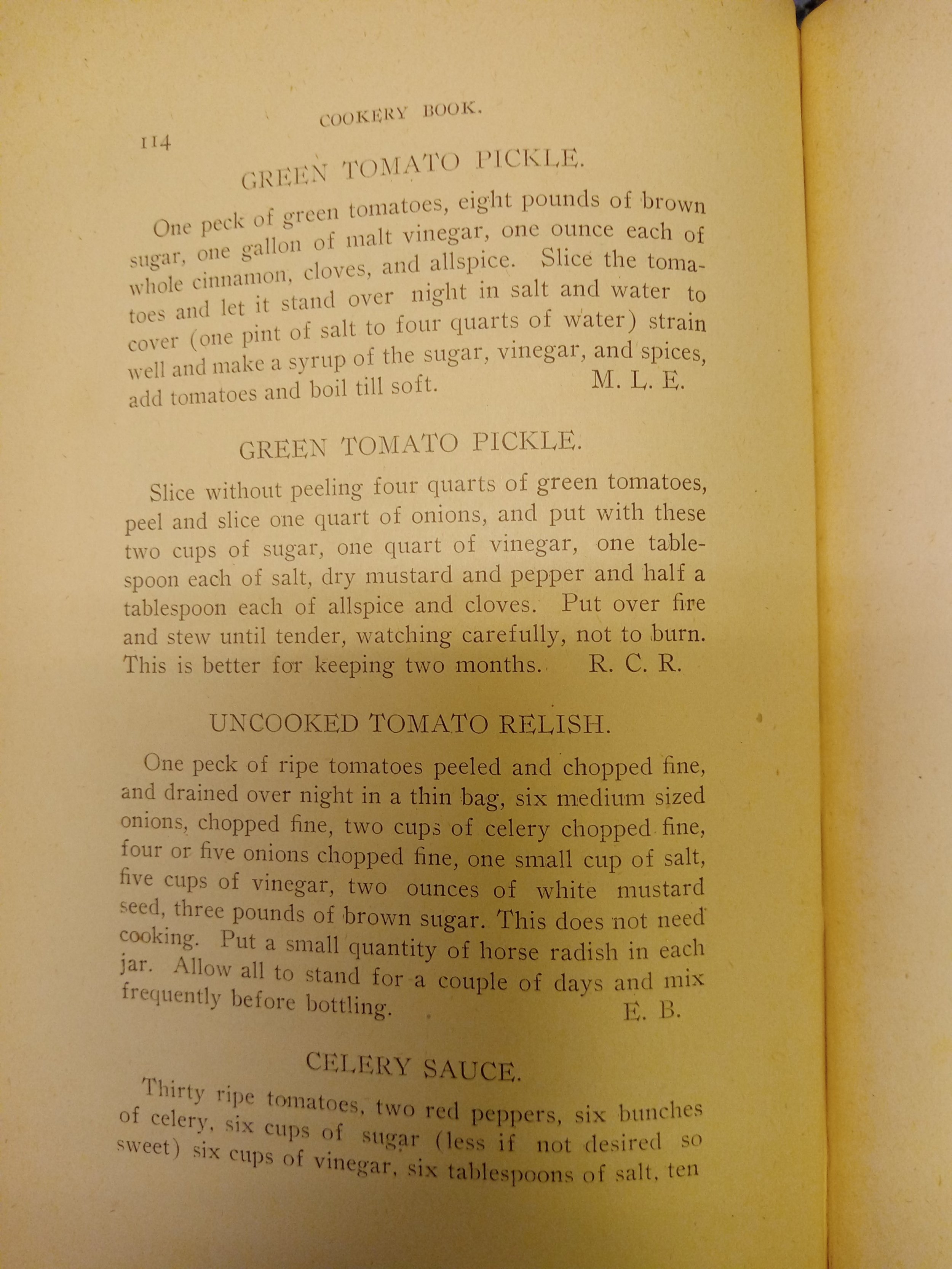

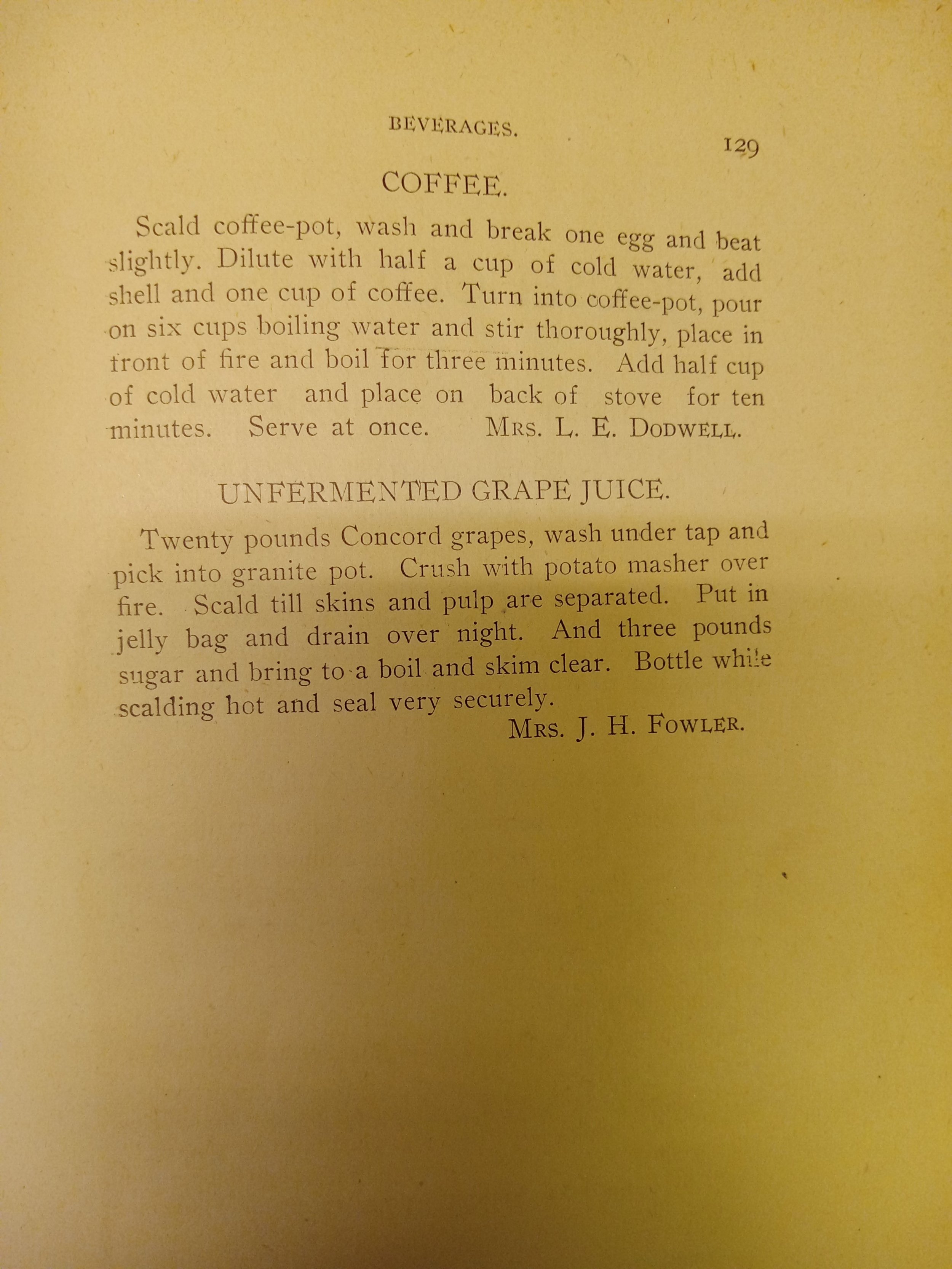

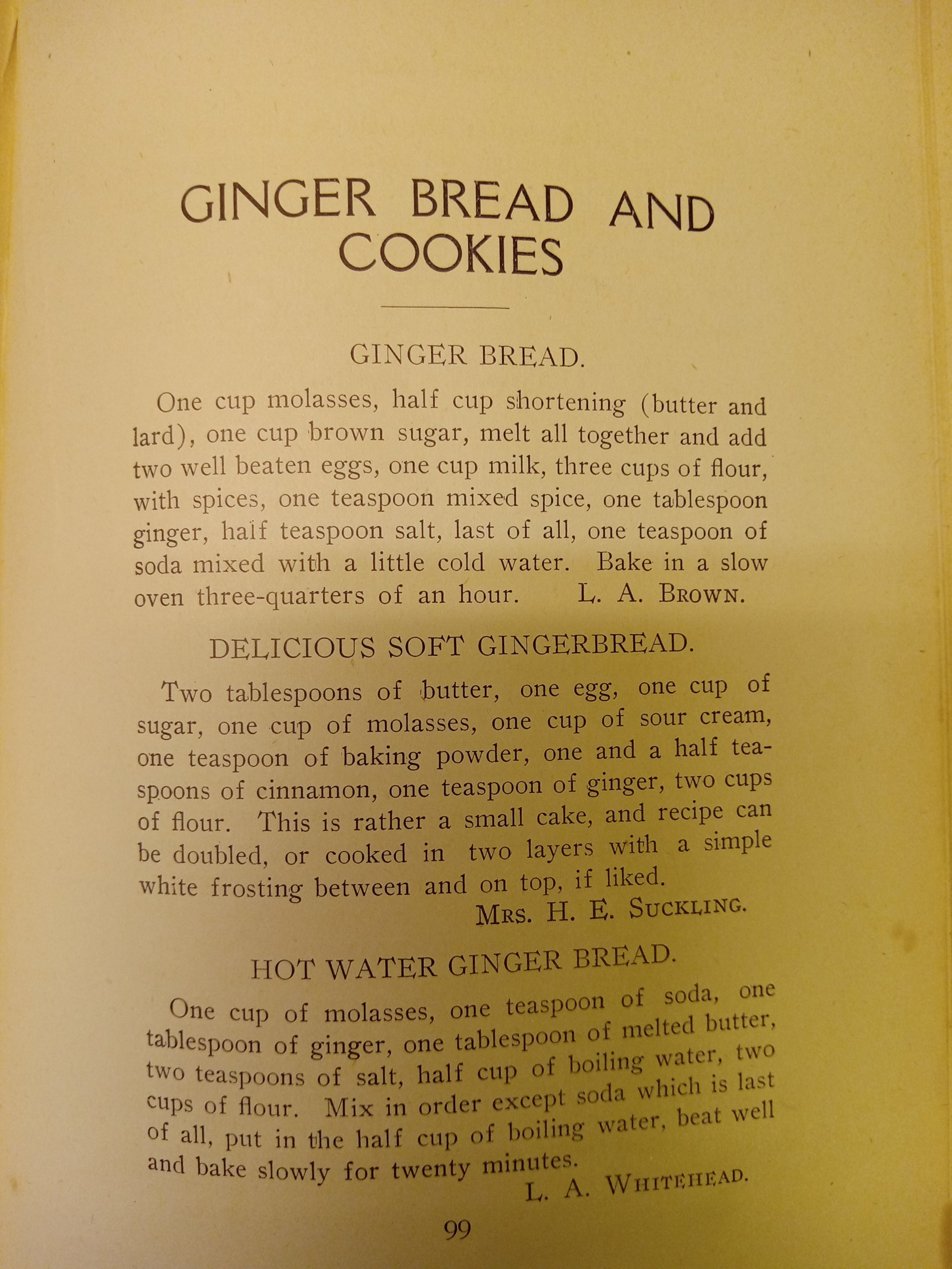

Starting in the 1880s, cookbooks began to move toward the recipe format we might find familiar, one that’s visible in Really Reliable Recipes and in most cookbooks published today, as well as online recipes. But Cookery Book stuck to the then-traditional format, which saved space by keeping ingredients and instructions together rather than separating them out. Even though one of the most iconic early American cookbooks, Fannie Farmer’s 1896 The Boston Cooking School Cook Book, was influential in getting formatting to adopt this new, clearer style with an emphasis on accurate measurement, it’s possible that that innovation hadn’t made its way to Canada – or that, because Cookery Book was a fundraiser, the Association of Women opted for the more economical formatting. Certainly the concern for accurate measurement isn’t reflected in recipes like “A Small Dish for an Invalid” and “Macaroni”! Cookbook historians think that this style of recipe format meant that books like Cookery Book were intended for expert audiences – they weren’t so much instruction manuals as reference sheets, giving experienced home cooks only what was needed to convey a new set of ingredients.

More than just the experience level of the women who would have used Cookery Book is communicated by its recipes: we can also see the distinct cultural reality of Anglophone Montreal in the 1910s. Raised pies – a staple of British cooking as far back as the medieval period – Christmas pudding, “Grandmother’s Curry Learned in India,” “Elderberry Blossom Wine,” and other recipes speak to the distinctly British, and distinctly colonial, character of the community. The colonial history of Montreal shows up, too, in the extensive section of pickles and sauces, jams and preserves, that are reflective of the way that early English settlers turned to preserving to deal with the harsher winters and shorter growing season of their new home. Preserves like chow-chow and chili sauce (which, as all good Anglo Canadians know, contains no actual chilis) are distinctly North American, even if mustard pickle and date chutney are Anglicised adaptations of condiments introduced to England as a result of colonising South Asia, which was still under British rule in 1912. On the flip side of settler-colonial frugality, the women who used Cookery Book would have experienced the luxury of Montreal’s thriving import trade: stocky English rhubarb could be brightened with exotic pineapple, grapefruits were plentiful enough to make marmalade, and the spices and molasses needed for as many kinds of gingerbread as one can imagine were easily accessible.

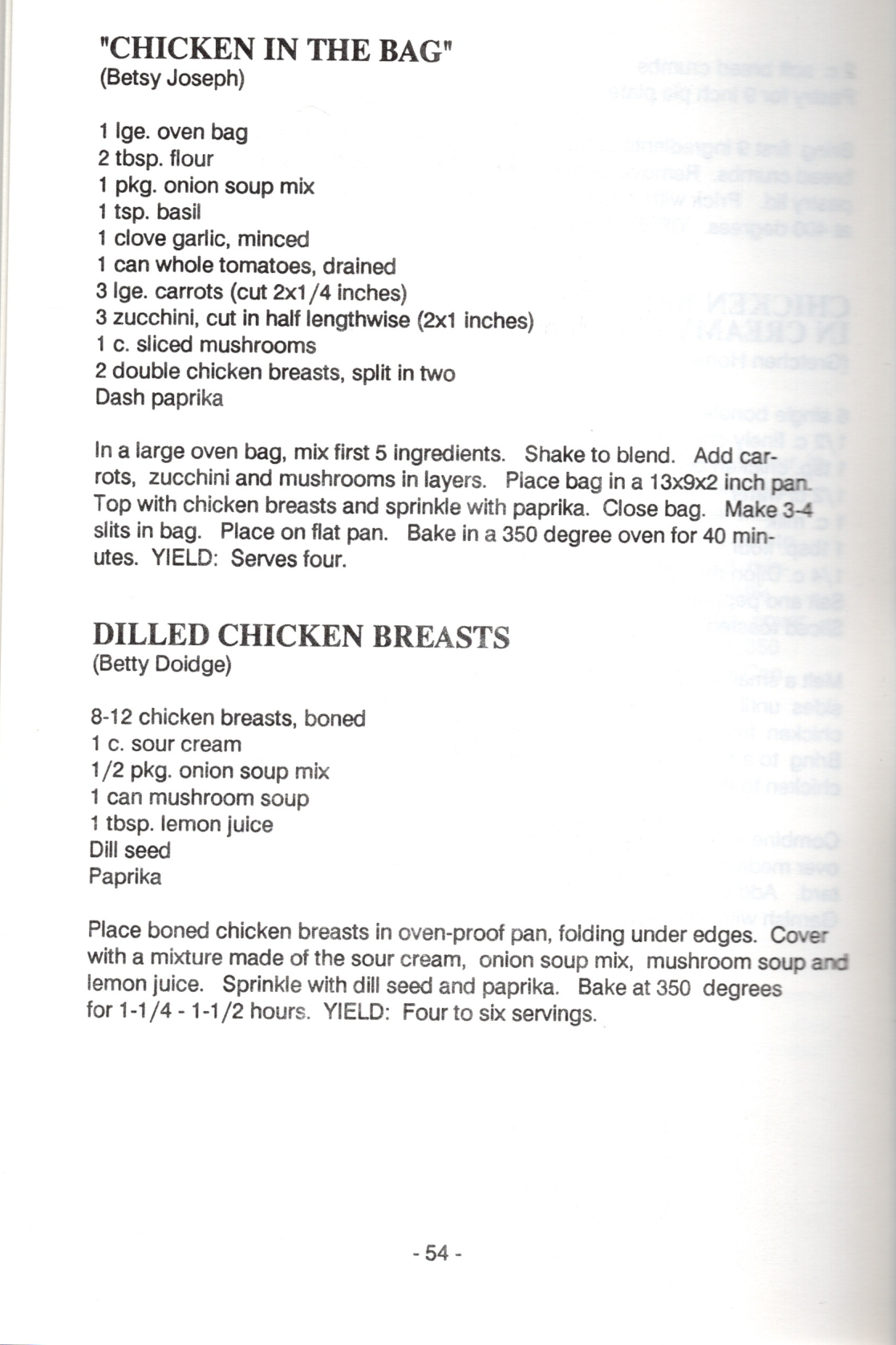

Extensive sections of baked goods, the tongue-in-cheek “Bloody Caesar” (“YIELD: Evensong”), and high-volume recipes of all kinds tell us that the Association of Women were thinking of entertaining, whether in their own homes or for all the many St. Matthias’ events over the years of their work. While there was no coffee hour in 1912, by 1989 many of the treats in the pages of both books would have been tested and approved by fellowshipping Matthians after Sunday services. It should come as no surprise that these recipes for Christmas cakes and puddings, altered slightly by trail and error, are still made by Fellowship chair Heather Barwick (and minions, many of whom are not able to be in church Sunday mornings but whose connection to the community is directly related to baking for it), to be sold at the annual Christmas fair. Betty Doidge’s Simnel Cake, or a variant thereof, shows up at coffee hour every Lent.

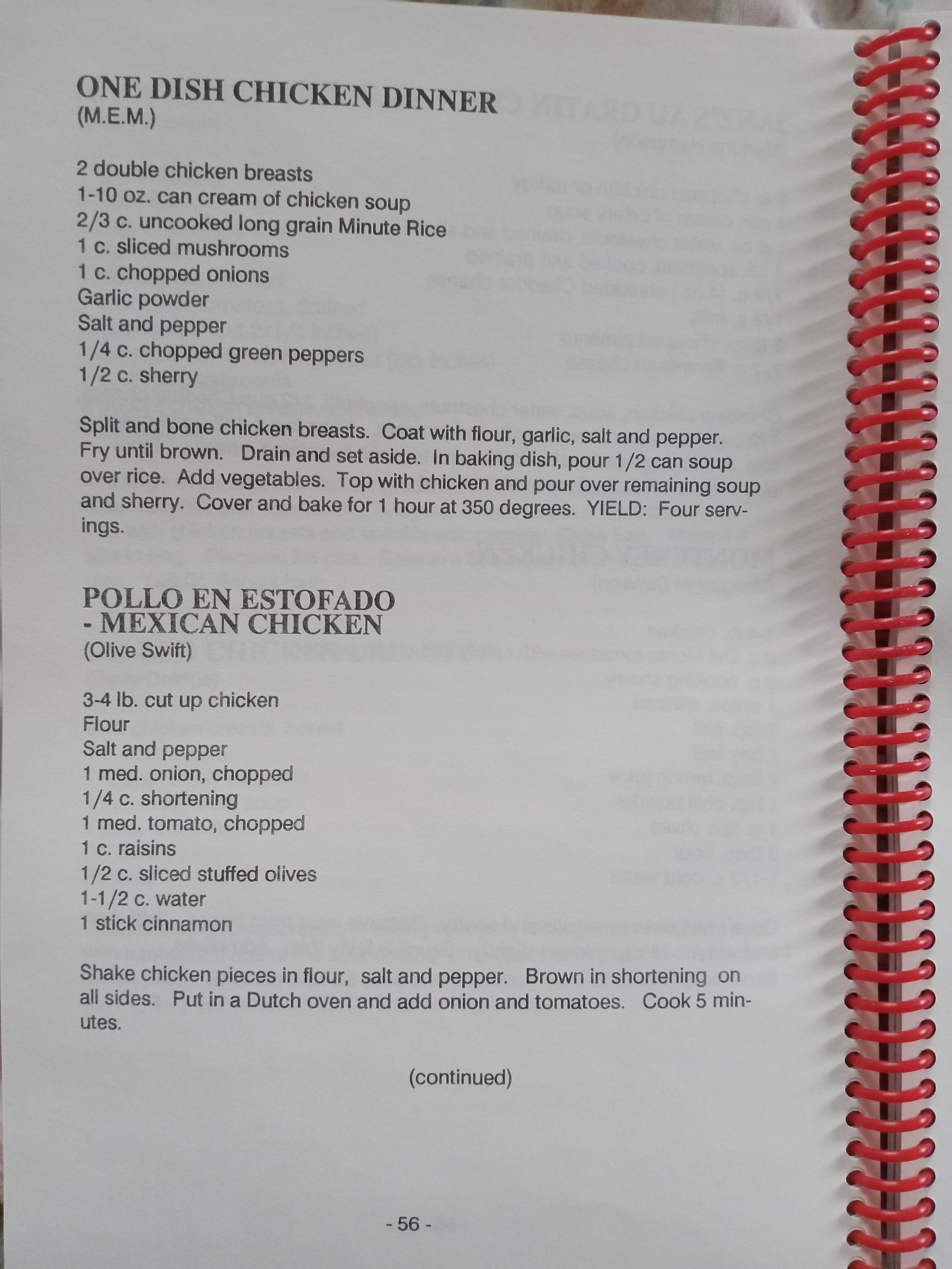

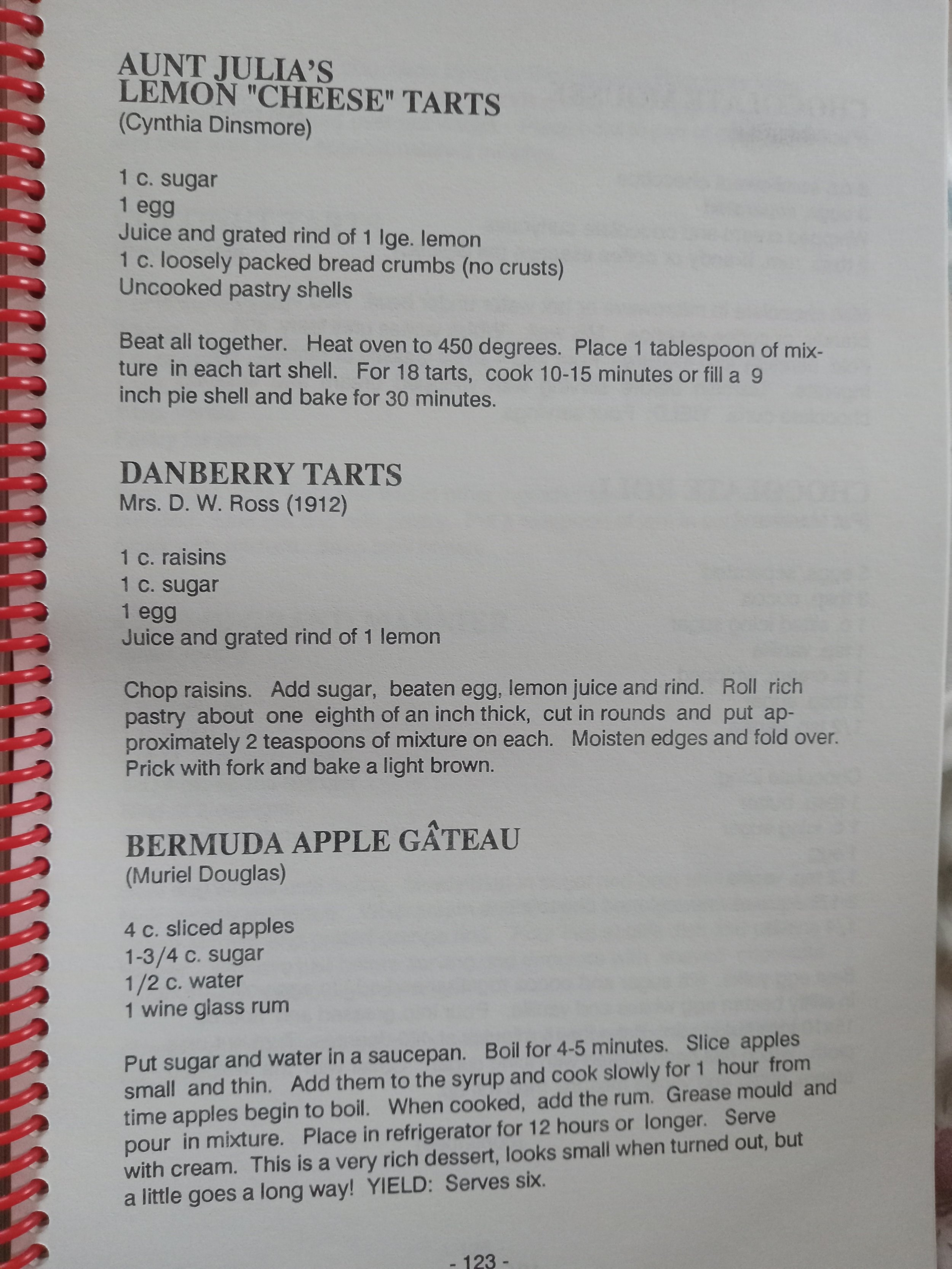

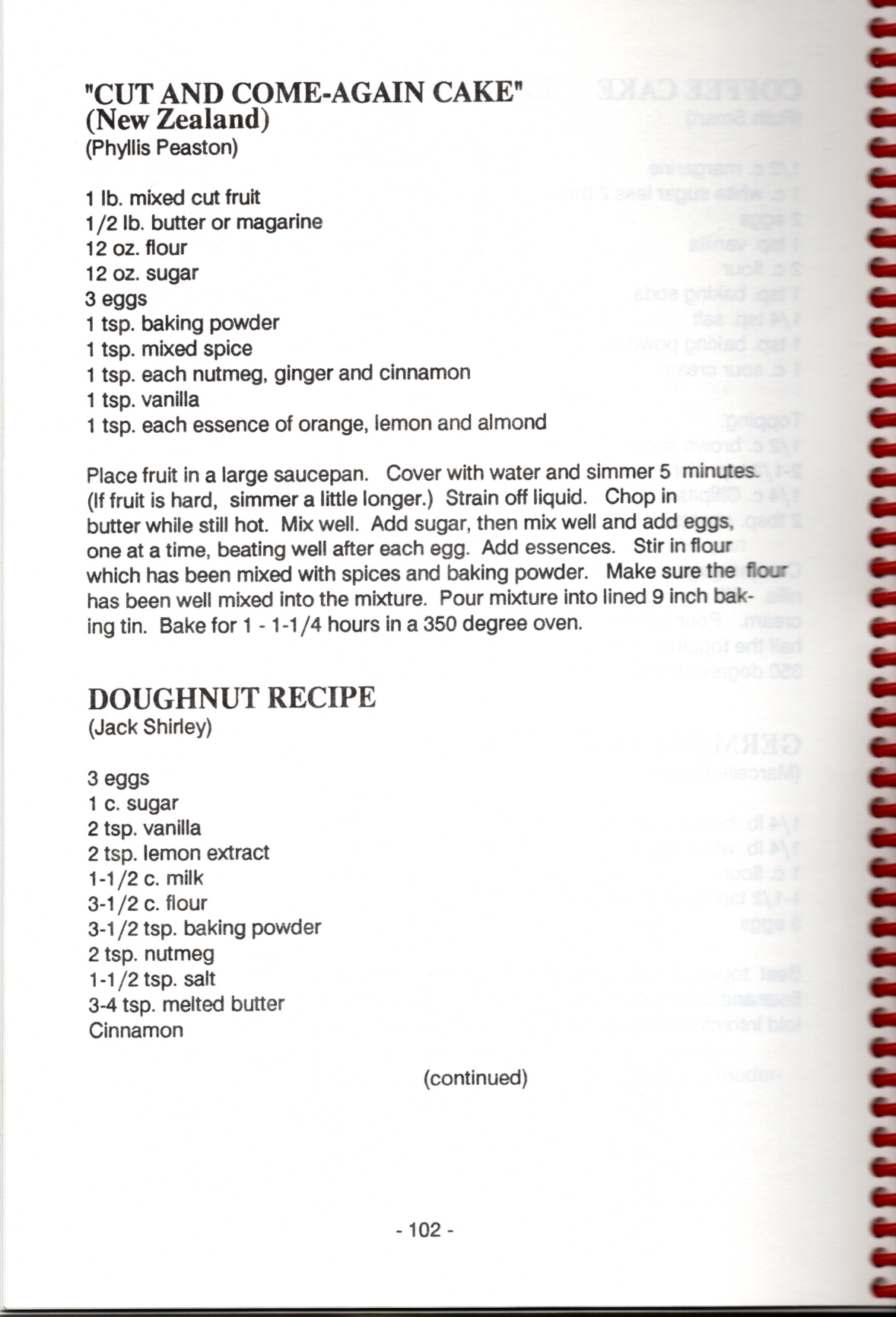

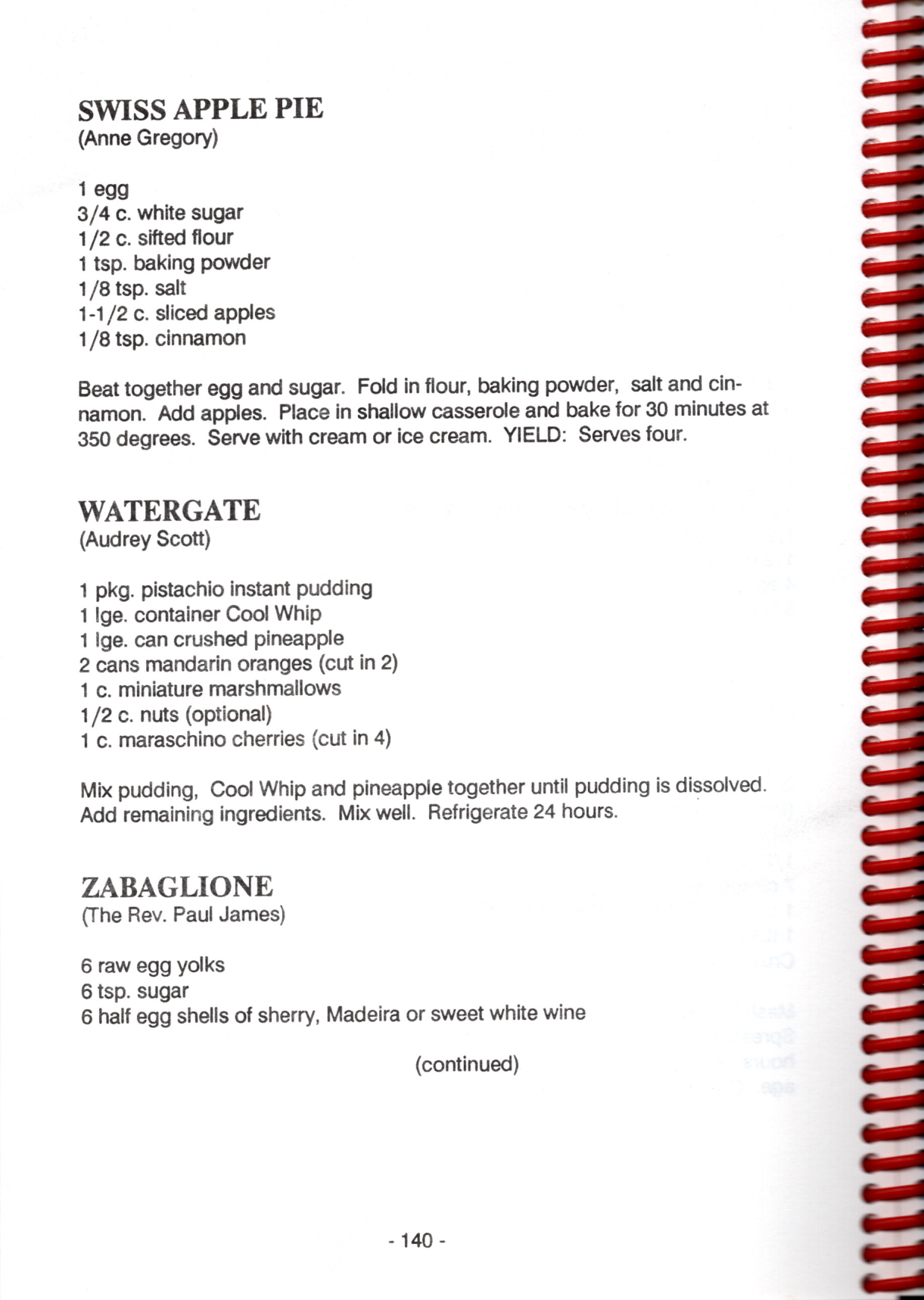

More again than simply encoding these multiple and overlapping identities, Cookery Book would have reinforced for the Matthian women who used it the rightness and goodness of those identities – and inadvertently made it more difficult, perhaps, for people with different culinary heritages to integrate into the Association of Women’s many food-based activities. Cookbook historian Kennan Ferguson calls this an “assimilationist ideology” that strove to unify a community under a single cultural identity. Thankfully, St. Matthias’ grew to embrace the cultural diversity of its community over the decades. By 1989, Italian-American dishes like Lasagne, and Zabaglione, Eastern European classics like “Helen’s Cabbage Goulash,” a New Zealand “Cut and Come-Again Cake,” “Senegalese Soup,” (PAGE 34) “Minced Meat with Spinach (Typical Kenyan),” (PAGE 46) “Pollo en estofado – Mexican Chicken,” (PAGE 56) and “Bermuda Apple Gateau,” (PAGE 123) shared space in Really Reliable Recipes with the English classics and a high proportion of French recipes. The Anglican Journal recently published an account of a similar change between two editions of a Toronto church’s cookbook, and although Really Reliable Recipes doesn’t go to quite the same heights of spice, it still reveals a greater celebration of the diversity of the Matthian community.

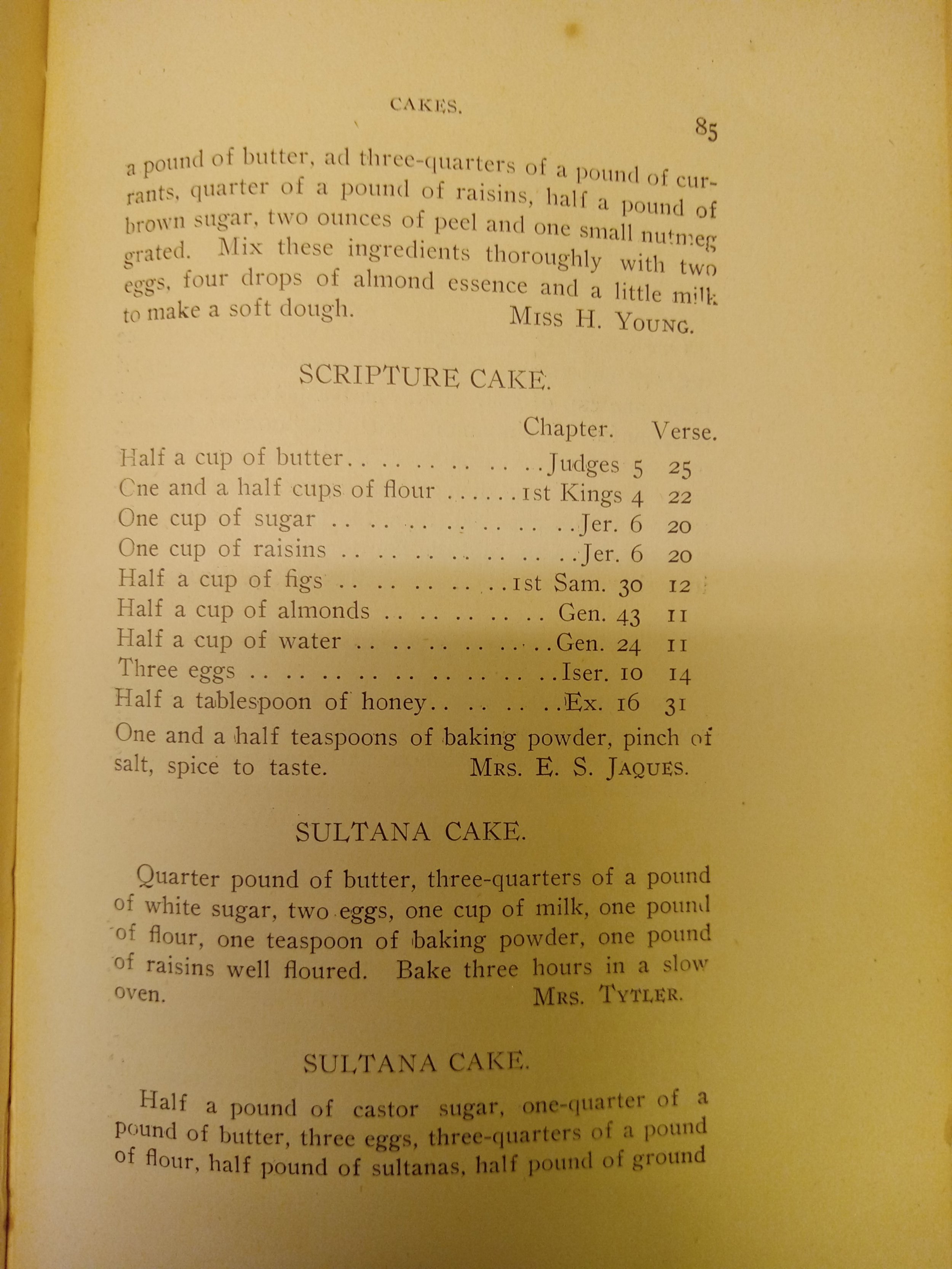

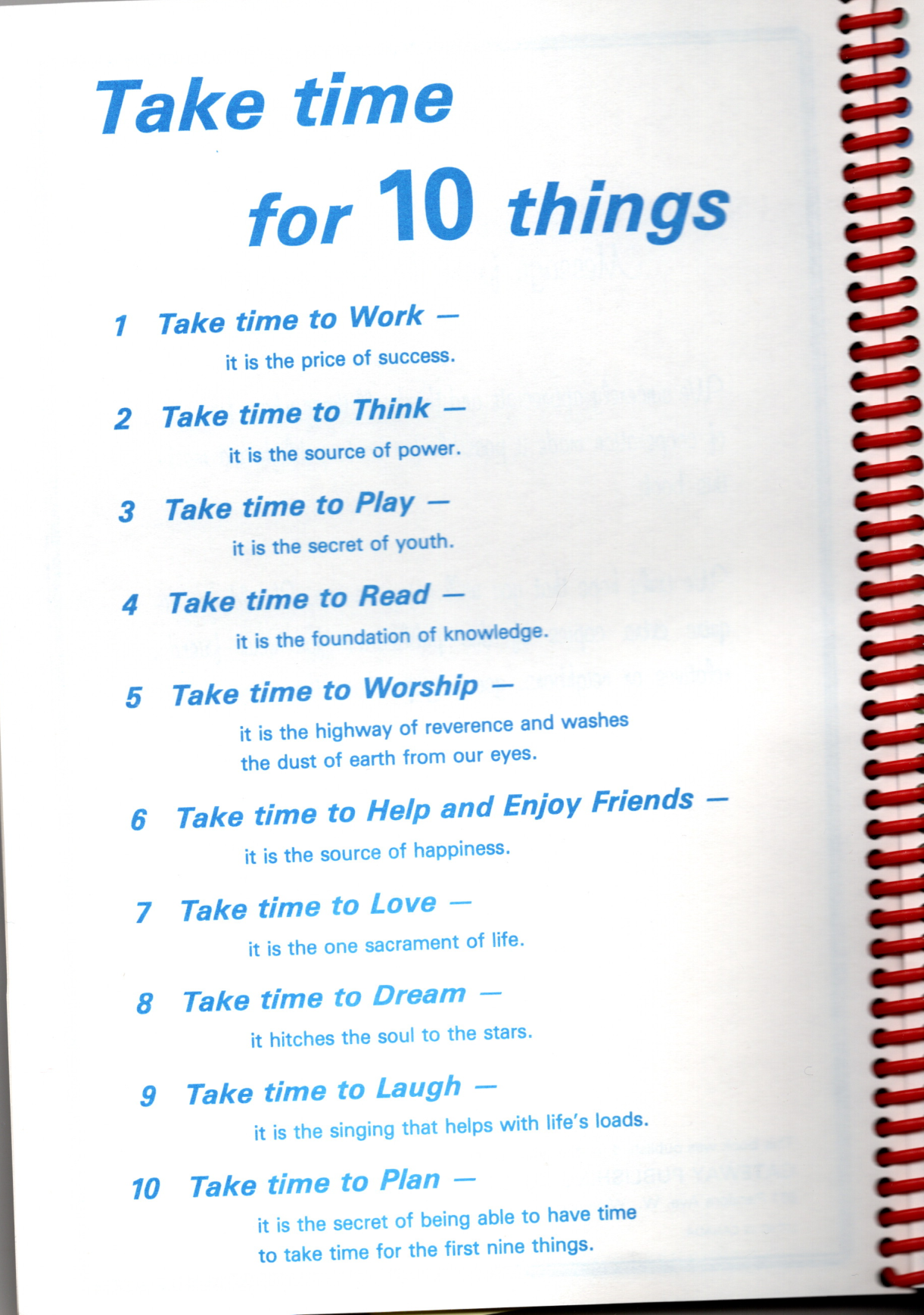

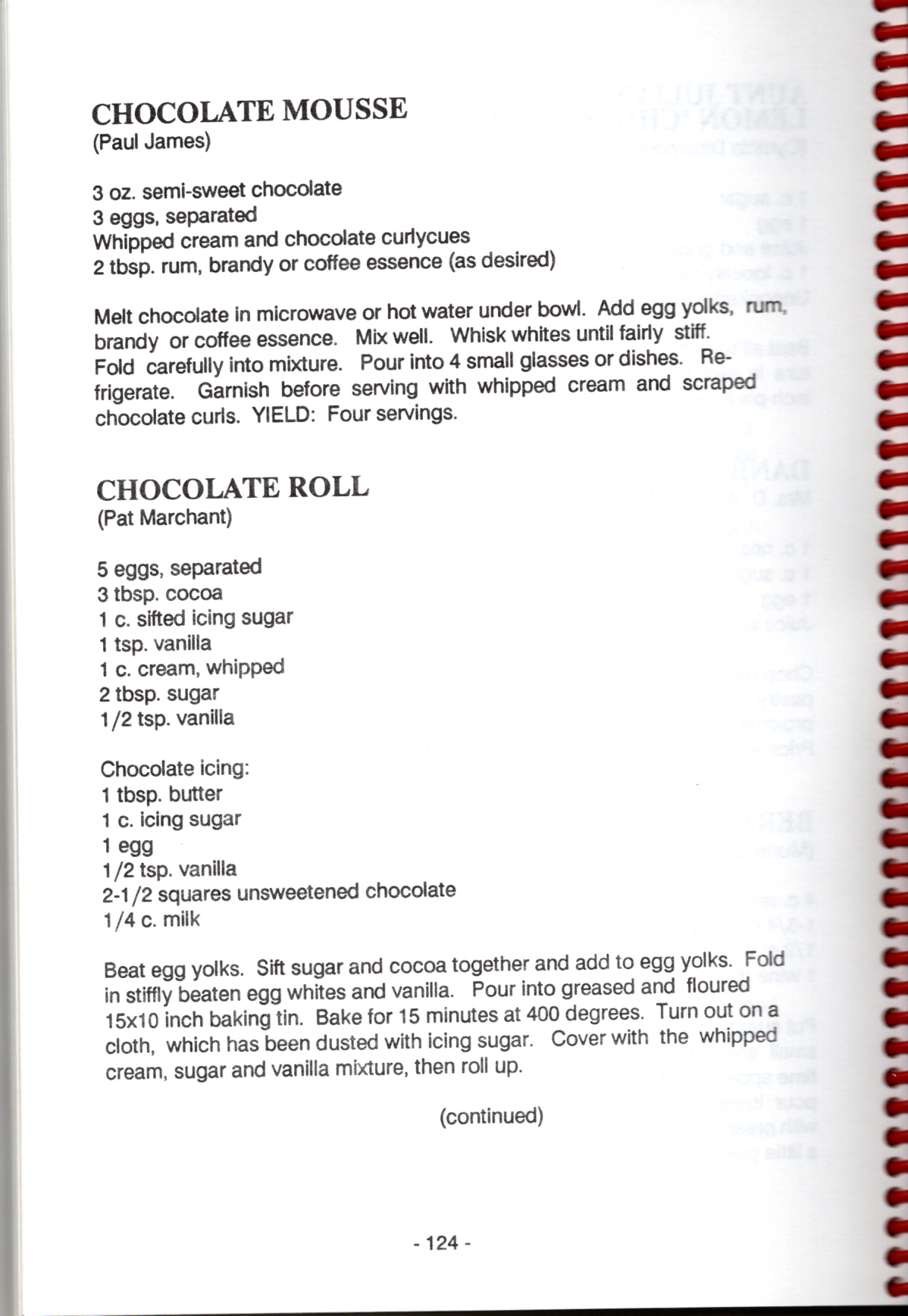

Both Really Reliable Recipes and Cookery Book share a common Christian self-understanding, however, which is evident in such places as recipes contributed by rectors (from Rev. Bushell’s 1912 Parker House Rolls to Rev. Paul James’ 1989 Chocolate Mousse), the ubiquitous Scripture Cake, and, of course, non-recipe material like 1989’s “Take Time for Ten Things” page and 1912’s “Rhymes to Remember.” But Christianity is also present in the books’ identities as cookbooks: cookbook historian Katherine Widner says that church cookbooks remind us that Christianity is a religion centred on the act of eating, and that these cookbooks by their sheer existence remind readers that “Jesus recognized and preached about the needs of the people being more important than adhering to ritual.” You won’t find instructions for setting up the altar here, although the same women were very much involved in doing that! Instead, these books invite you to take your faith home and use it to feed someone, to bring the fruits of your kitchen and the work of your hands into your community and use them to celebrate, fellowship, and comfort each other.

And that’s exactly what the Matthians of 1912 and 1989 did. These books tells the story of a changing population of women sharing the struggles and joys of keeping house and keeping the church, finding ways to enrich each other’s lives and support the institution that was the centre of their communal life. Cookery Book shows us how, in the words of historian Emily Jean Bailey, older women in the church “helped ease the transition of the younger female members from girlhood to Victorian womanhood,” while Really Reliable Recipes reflects the contribution of men, a shift in gendered labour that would result, just a few short years later, in the gender-agnostic Fellowship of St. Matthias’ succeeding the Association of Women in feeding the community.

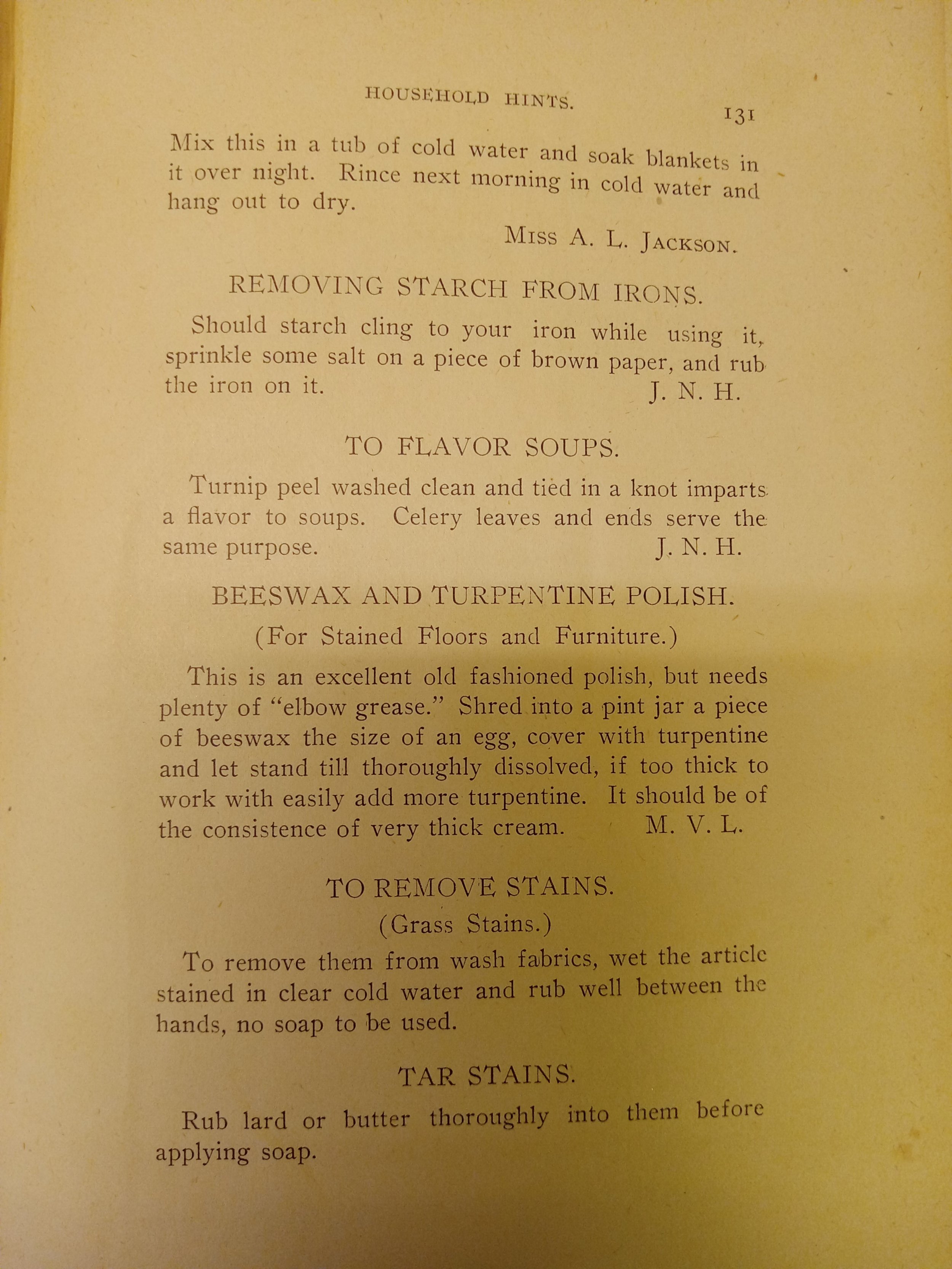

There is so much more we could say about Cookery Book – about the way the Association of Women’s power in the church was limited to this one sphere despite their formidable fundraising and organising power and the sheer weight of the church’s success that rested on their shoulders (and even still it is their husbands’ names that grace the pages!); about the activities of husbands and children in this community implied by the kinds of stains the 1912 book shows how to clean; about the frankly unsettling method of coffee-making that probably reveals something about how beans were processed in the 1910s. Likewise, Really Reliable Recipes has much to tell us about the economic situation of the 1980s and the demographic makeup of Westmount, while recipes like “Watergate” show how communities grappled with historical events (whether this recipe was invented before or after the scandal, the choice to retain the name tells us something!). Church cookbooks, as the United Methodist Church’s communications department says in their own cookbook retrospective, are time capsules.

They are also ways of sharing community with each other at a distance, something the Matthians of today know how to do all too well. This fall, when your humble historian is ready for something rich and sweet, I’ll invite Mrs. H. E. Suckling and her “Delicious Soft Gingerbread” into my kitchen to spend time celebrating our mutual love of all things molasses, or perhaps Pat Marchant and her “Chocolate Roll” to take joy in the magical flexibility of a careful sponge cake. What will you make?