June 11th: Remembering War, part one

St. Matthias’ was officially founded as a mission of St. George’s, Place du Canada, in 1873, which means our community is 150 this year! For the next 12 months, we’ll be diving into the archives to shine the spotlight on particularly interesting parts of our history.

The Memorial Chapel in the North Transept, as it stands today

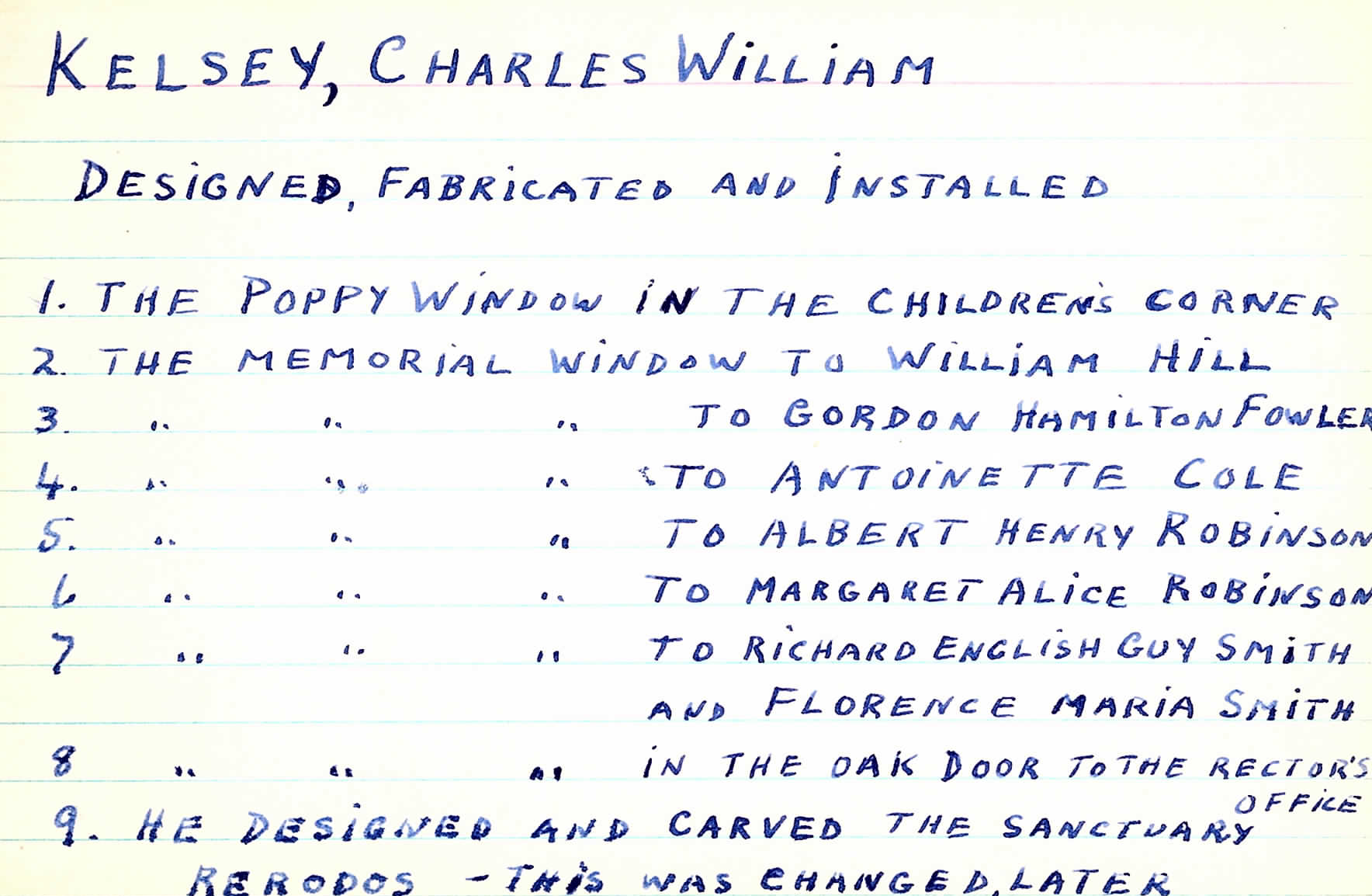

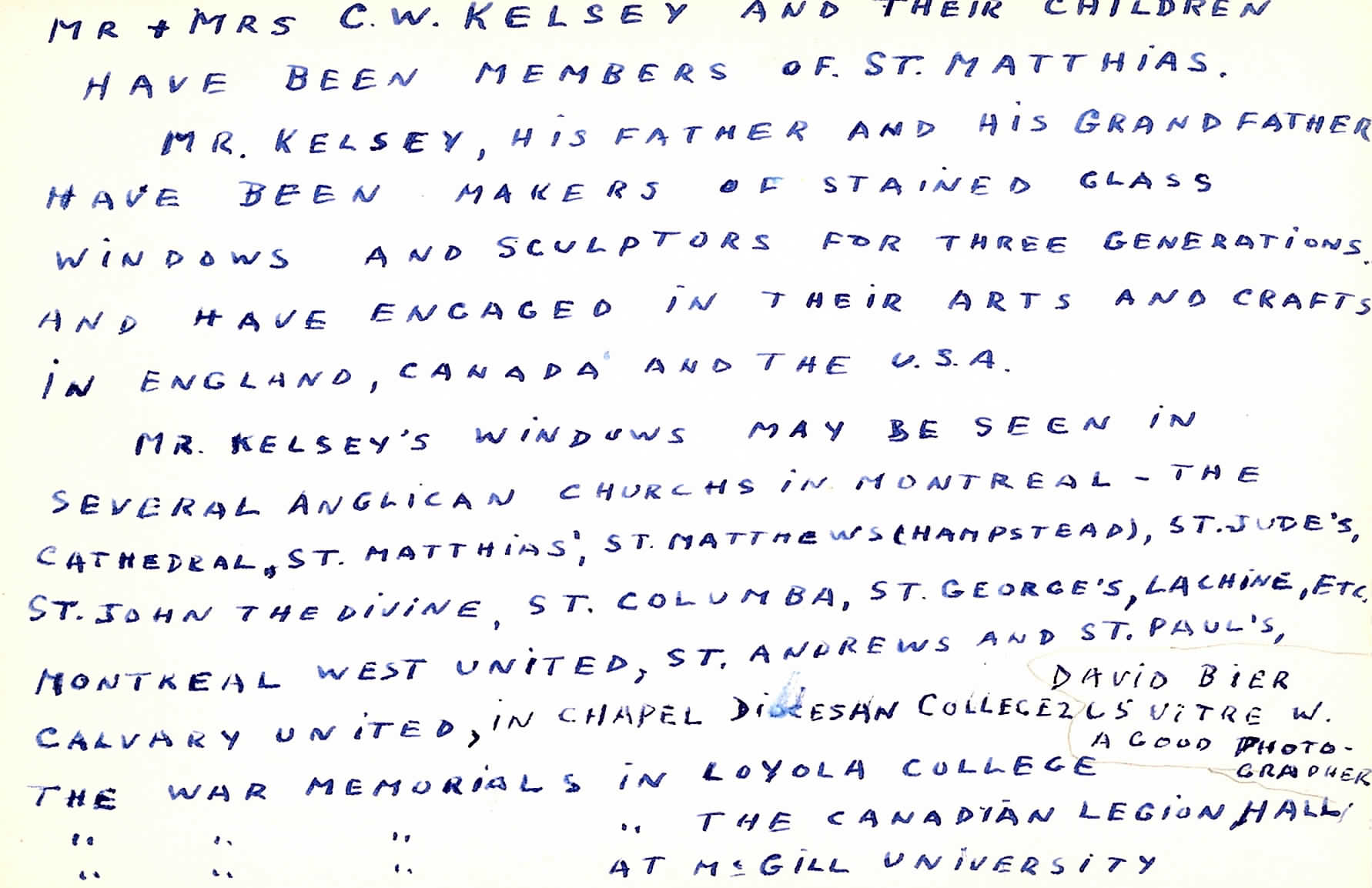

St. Matthias’, like many Protestant churches in Canada, is covered in memorials to dead soldiers, many in their late teens or early twenties. Whether you’ve read a plaque, looked up at a stained-glass window, or taken a moment to peruse the honour roll in the Memorial Chapel, it’s hard to avoid the reminders of what, and whom, this parish lost during the World Wars. The desire to memorialise these boys coincided with two important aspects of St. Matthias’ life from the 1920s through the 1960s: the relative affluence of a settled parish with a large space to decorate, and the move away from what art historian Shirley May Baird calls “prefabricated, uninspired patterns” in stained glass that had been designed in England for mass production. This latter trend was represented, at St. Matthias’, by a parishioner named Charles William Kelsey.

Gordon’s window, which cost his mother $200 ($3400 in today’s money), is also one of only two windows to have been catalogued by Veteran Affairs Canada. It displays what war historian Jonathan F. Vance identifies as one of three main features of WWI memorial windows in Canada: the defence of Christianity. “Canadians held fast to the belief that their sons and daughters had gone to war,” he writes, “’as champions of...mercy against ruthlessness, of justice against iniquity, of decency against shamefulness, of good faith against perfidy, of Right against Might, of peace against war, of humane and Christian civilization against savage and pagan barbarism’” (quoting historian H.J. Cody’s 1919 introduction to a history of the Great War). Gordon’s window shows “Christ enthroned receiving the soul of the soldier,” an indication that although his mother may have preferred her son alive, she was nevertheless comforted by the fact that he had been martyred as just such a champion and had received his reward in heaven.

Vance’s second feature is also present in St. Matthias’: in the window dedicated to John Albert McConachie, we see a knight and an angel, and the verse “Be thou faithful unto death and I will give thee a crown of life.” John’s window was commissioned by his parents’ neighbours, William and Ethel Petts, and was installed above their regular pew. Vance says that the figure of the medieval knight was a common allusion to the Crusades in WWI memorial glass, because Canadian Christian rhetoric surrounding the war regularly framed it as a crusade, specifically one against forces that threatened the Church. “The constant repetition of the figure of the medieval knight” he says, “was reinforced by frequent reference to certain suggestive phrases from the Bible. ‘Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life,’ from Christ's Revelation to John, appears […] to remind parishioners of the piety of the soldier.” John, like Gordon, was receiving his reward in heaven for his knightly courage in the crusade to preserve Canadian Christianity – hopefully a comfort to his three sisters.

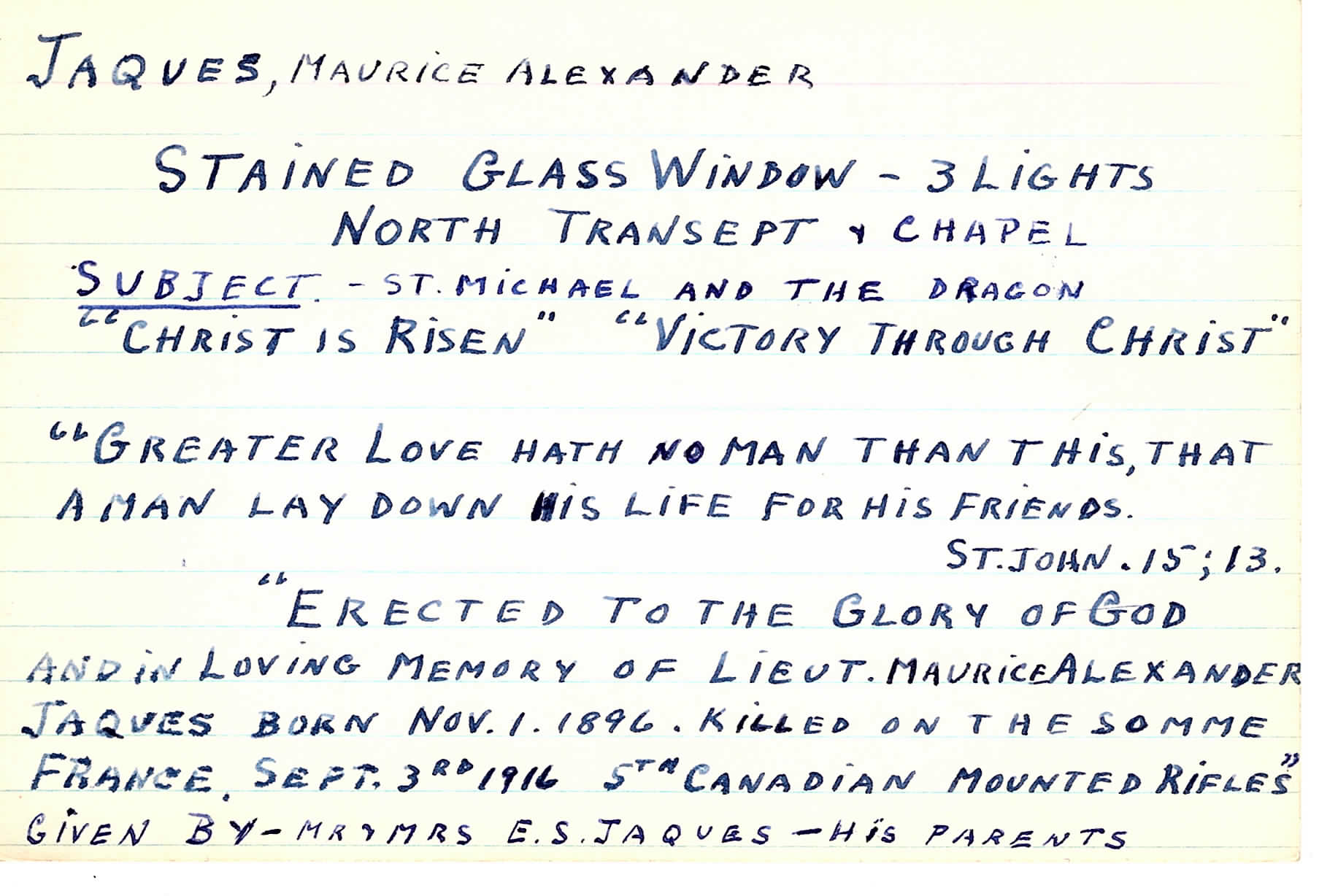

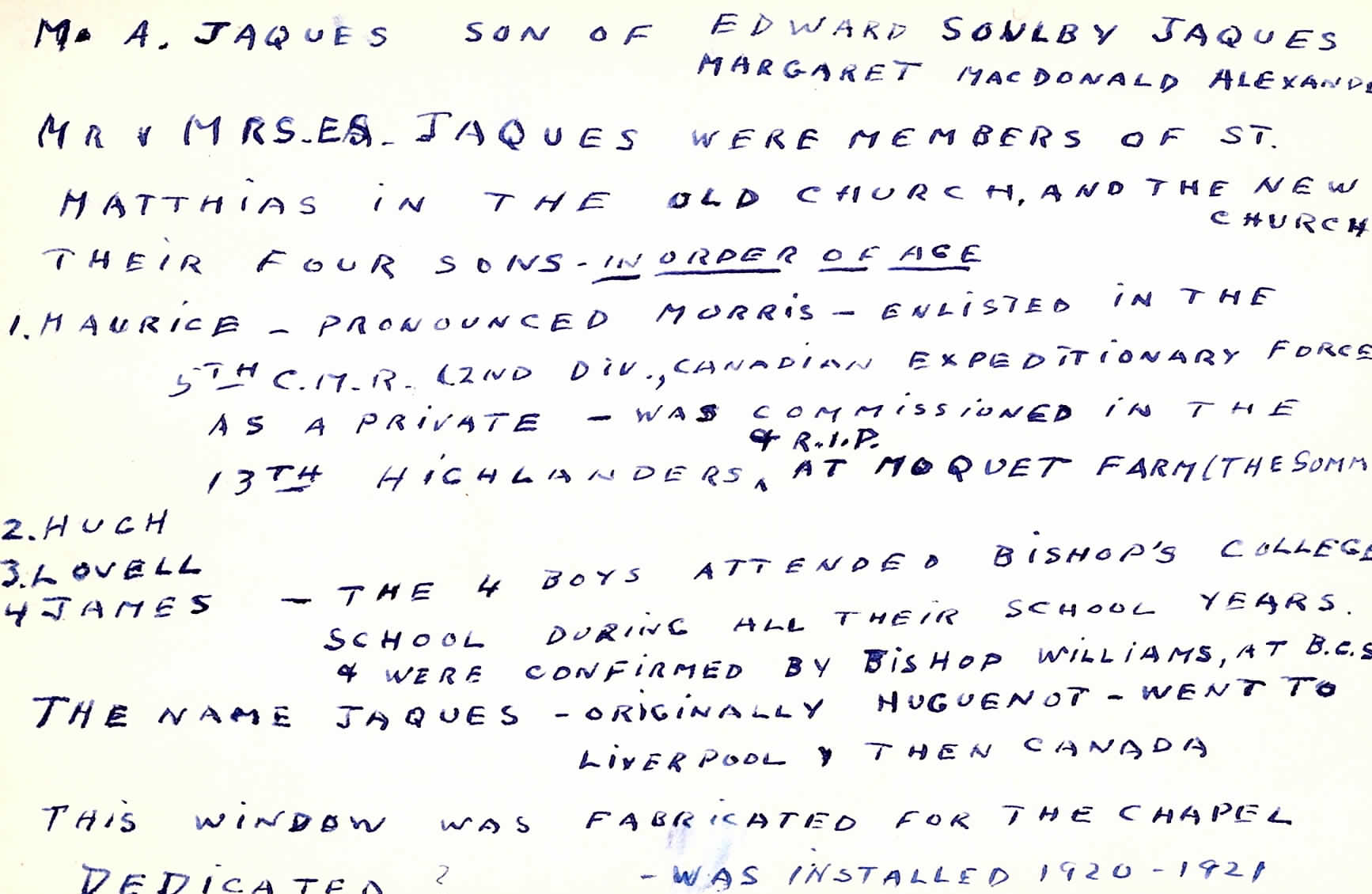

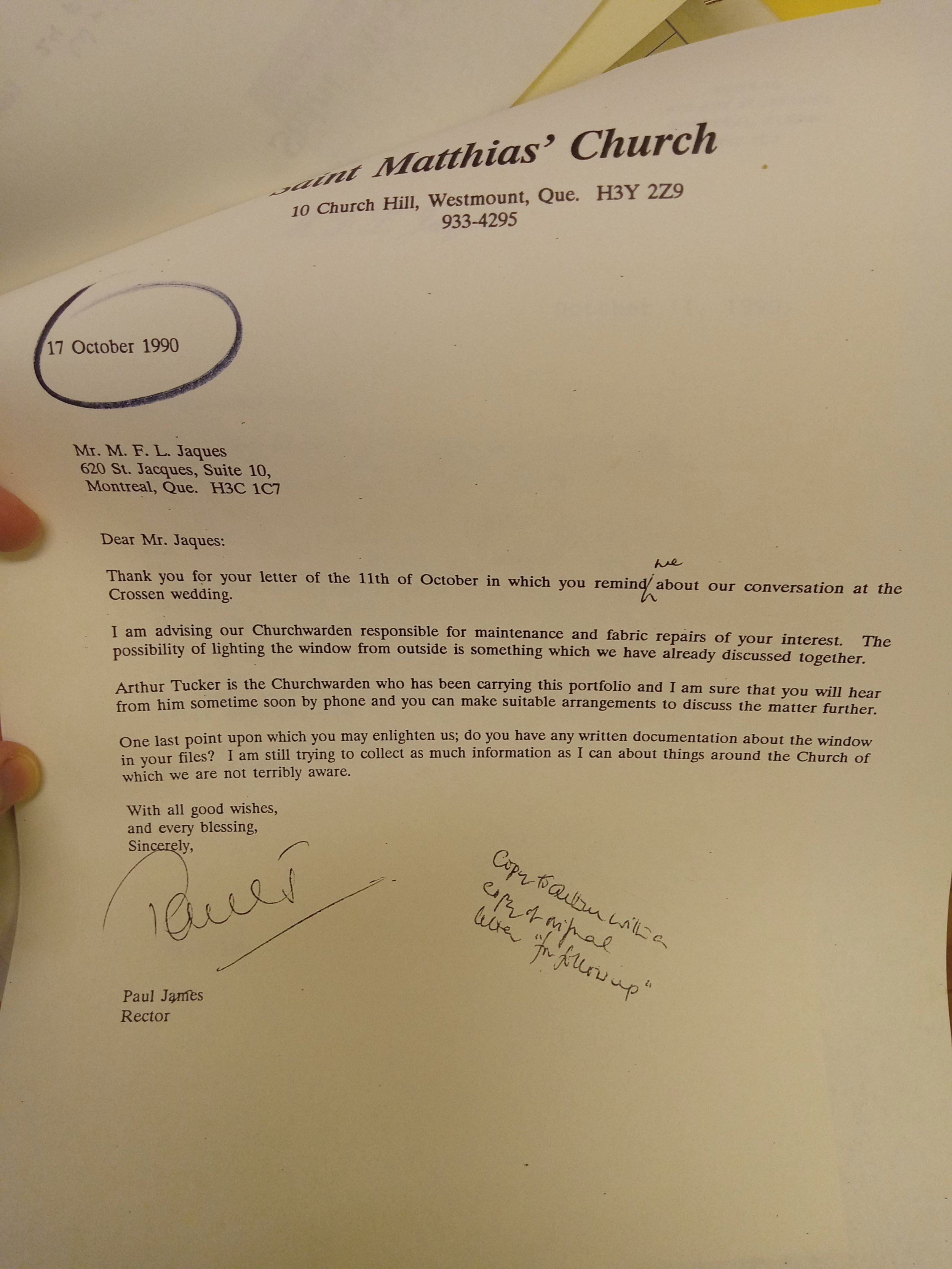

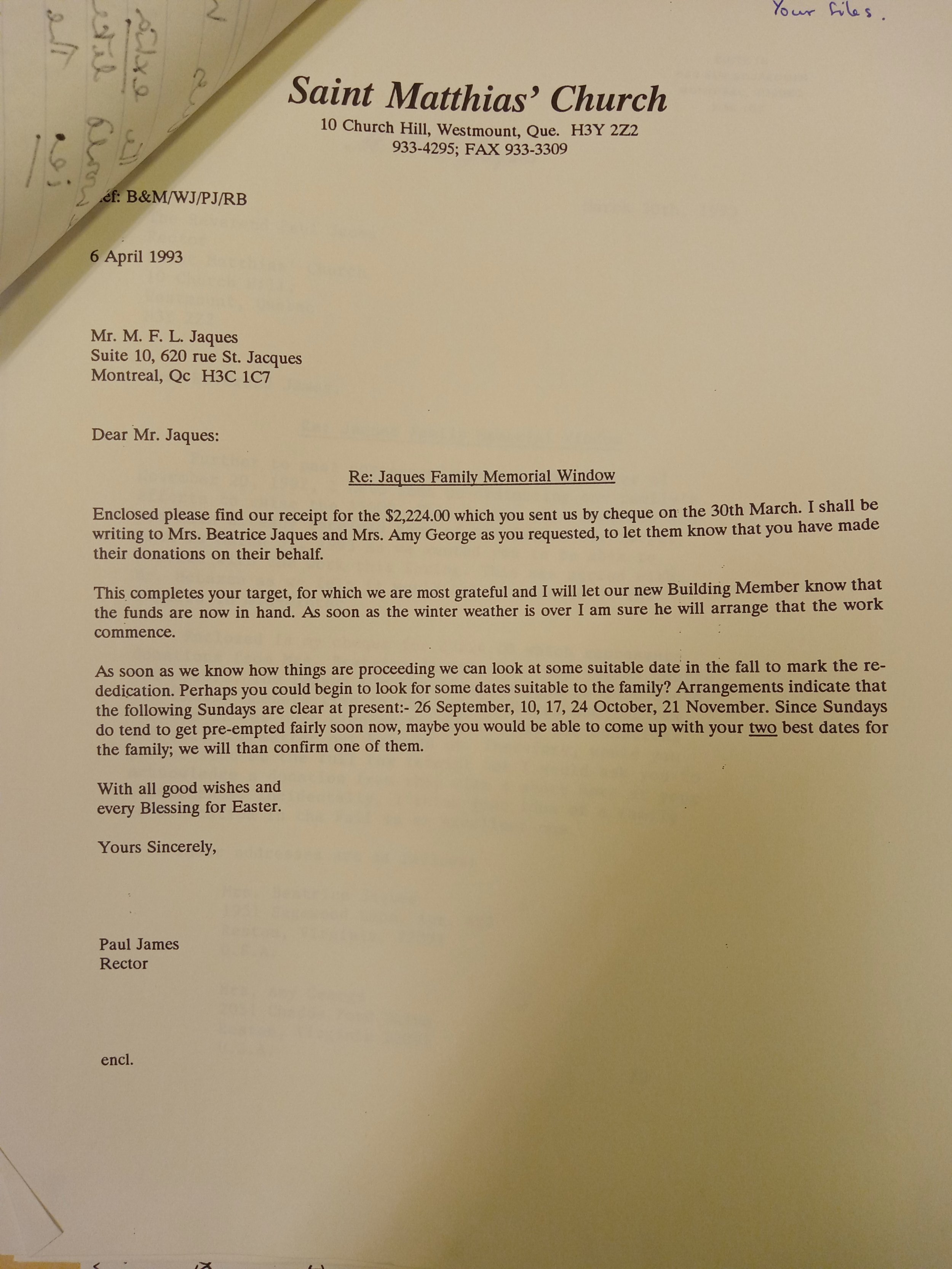

Finally, we turn to the third window in this trio of early Matthian losses: the window that currently occupies our North Transept, dedicated to the memory of 20-year-old Maurice Alexander Jaques. The inscription the Gospel of John, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends,” was one of the verses that Vance says was often used to “perpetuate the notion of a unity between the individual soldier and Jesus Christ […] Like Jesus, the soldiers fought to defend their faith and were willing to sacrifice their lives to save humanity.” The window itself depicts St. Michael, one of the most frequently represented saints in war memorial windows according to Baird; “after World War I, the figure of the Archangel Michael was selected as the patron saint of the Air Force [and] Since these symbolic figures were not connected with any specific war or battle, they acted as timeless statements about victory […] as well as creating a mental distance from the reality of warfare.” Maurice, identified with Jesus and symbolising the victory – “through Christ,” as the window’s text reminds us – of justice against iniquity, became a sign of hope to his family and his parish. A later Maurice Jaques would, in the early 1990s, gather his family together to repair and rededicate the window, demonstrating the extent to which it fulfilled its role for the family at least.

In 1929, when the Men’s Association presented a proposal to the Corporation to establish a Great War memorial in the church, they, too, were focused on the fact of sacrifice rather than its horrible details. War memorial stained glass had been installed at St. Matthias’ as early as 1920, but the Men’s Association thought that there was a need for “a suitable War Memorial” for the church as a whole, to name all those whose families had not been able to dedicate windows and plaques. Then-rector Rev. Gilbert Oliver, who had been in his post only a few months, allowed the Men’s Association to bring the idea to a larger body, but the memorial would not be completed and installed for nearly twenty more years.

In the meantime, the Memorial Chapel was finally decorated and furnished in 1934, according to the parish history published in 1935, but it was not intended at the time to be a memorial in this martial sense, despite Maurice’s window dominating the space. The 1935 history describes it as “a symbol of life through the ages” and “a link with the past.” The list of donations we can see above, and the fact that the chapel houses the altar of the original wooden church, attests to this intention. Its current status as a chapel with a decidedly militaristic bent is relatively recent in the life of the building, and many parishioners may recall the events of 1973 that led to this change – to be covered in a later post!

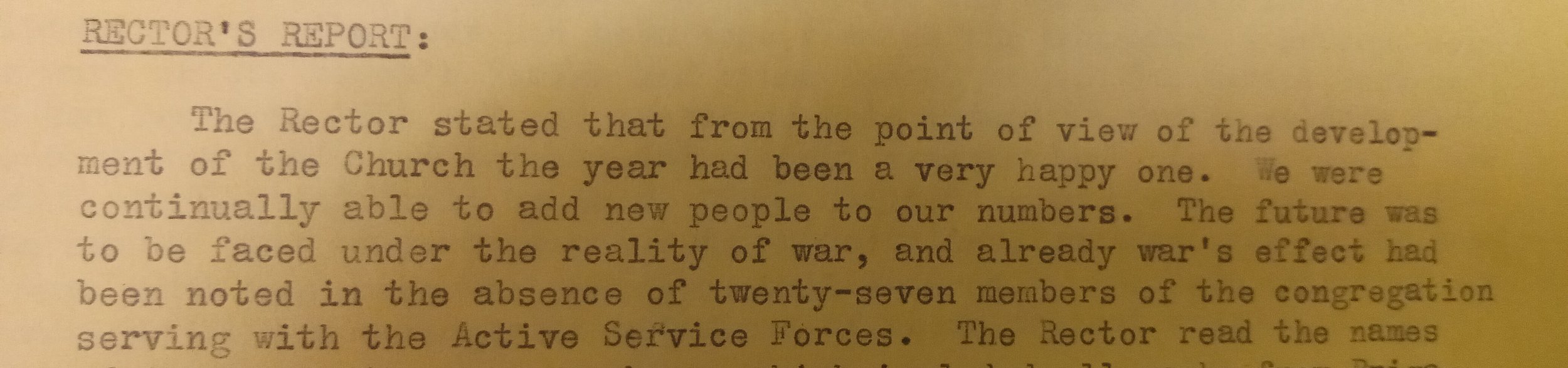

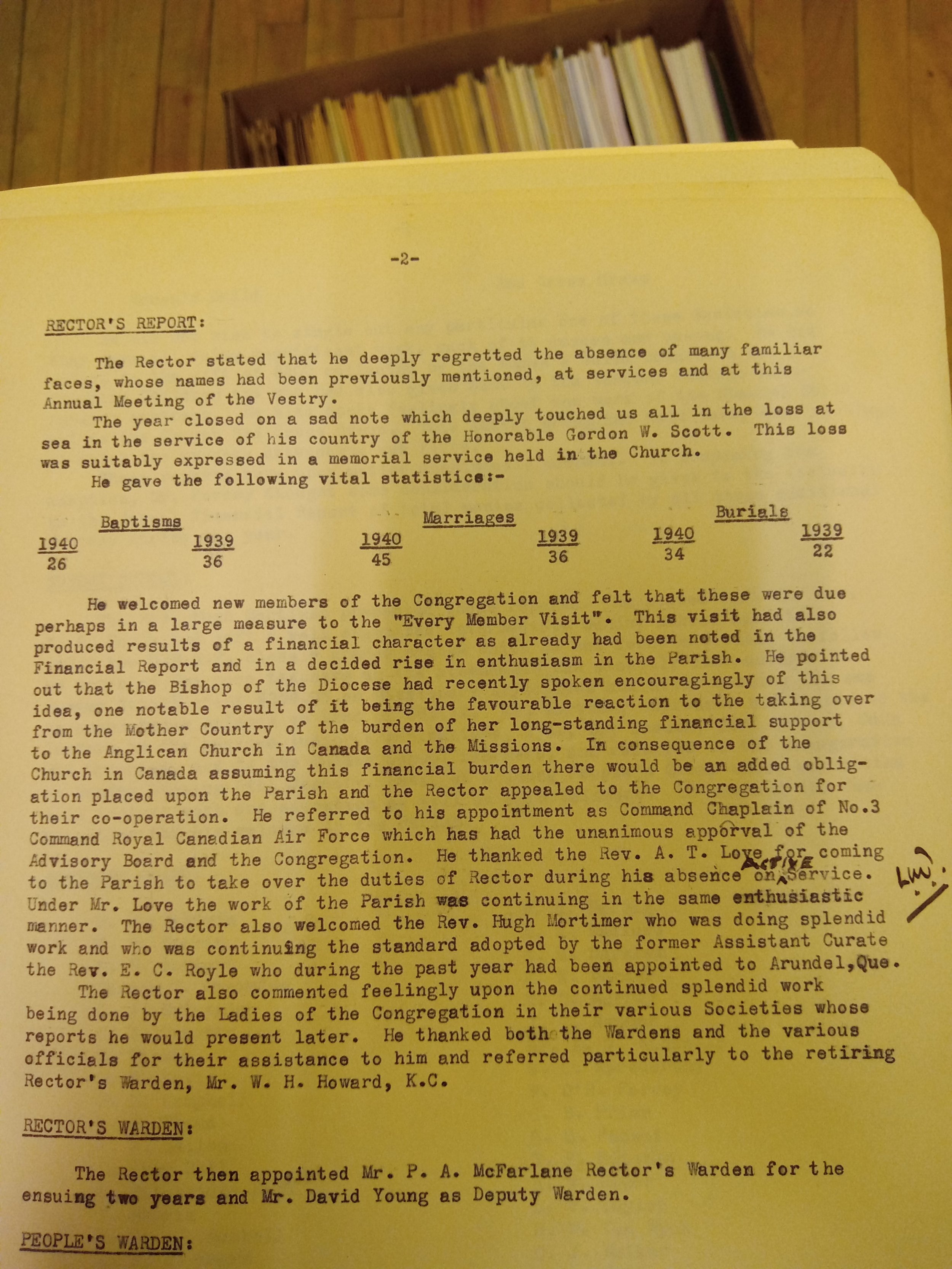

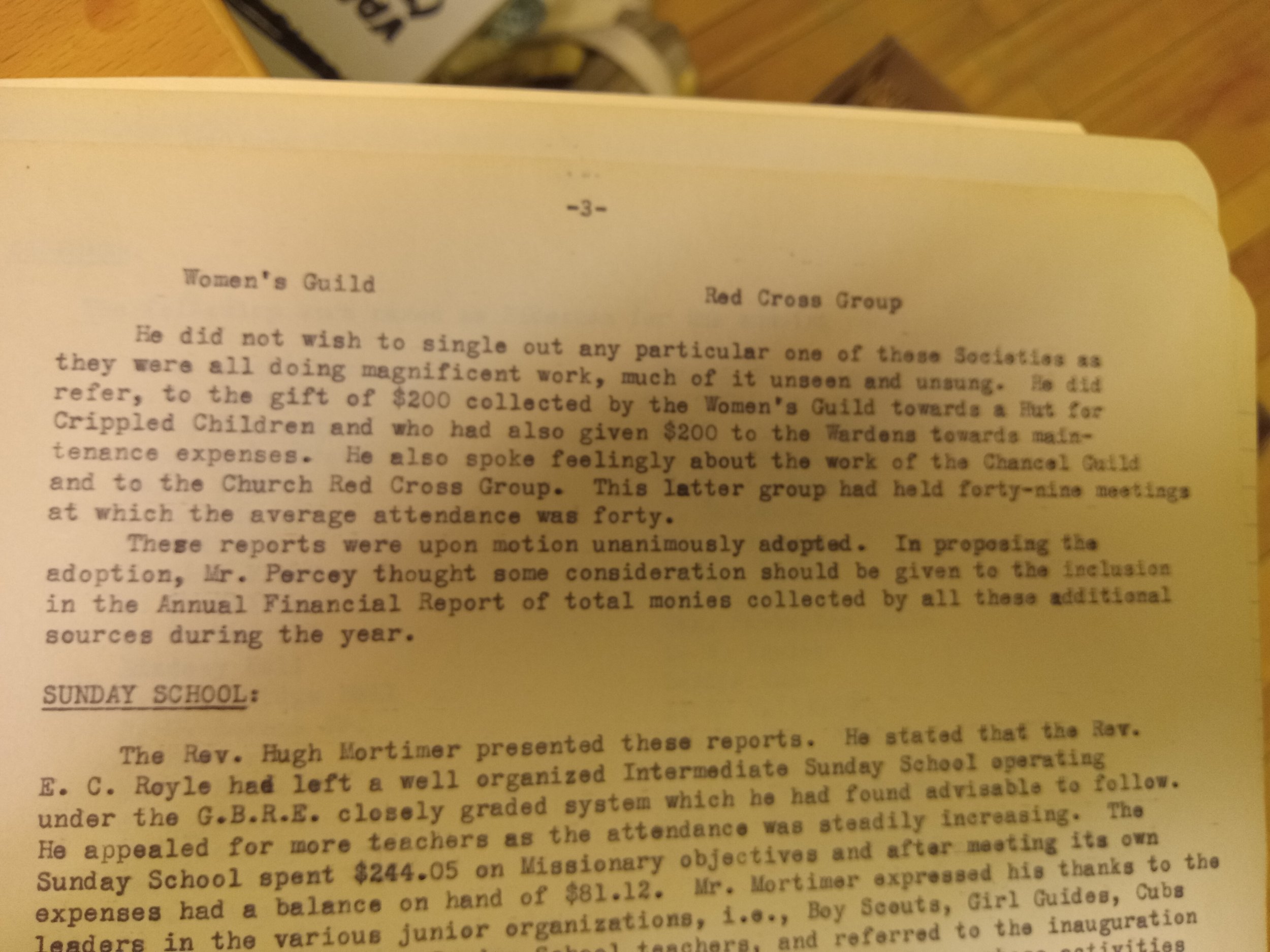

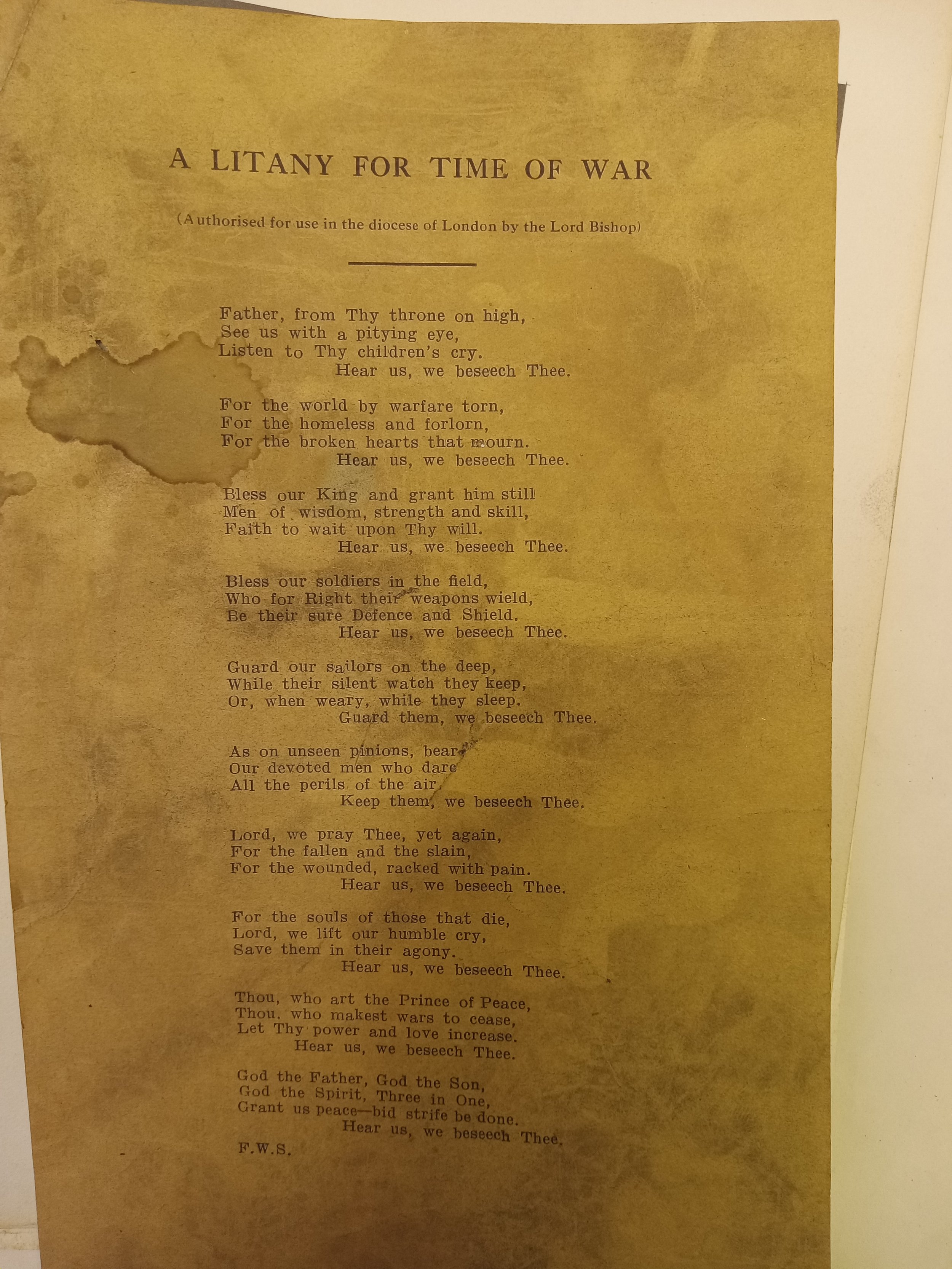

Memorial chapel decorating efforts and war memorial planning alike were set aside as war arrived once again. 1939 saw twenty-seven members of the church leaving to enlist and 1940 saw Rev. Oliver being appointed Command Chaplain of No. 3 Command Royal Canadian Air Force and the formation of a Red Cross Group under the auspices of the Women’s Association, which met forty-nine times over the course of 1940. Such was the turmoil that our archives don’t even have Vestry minutes from 1942-44, although 1945’s Vestry minutes mention that Vestry was held in 1944, at least. Unlike the Great War memorial windows, which were commissioned and installed after the war’s end, WWII windows began to be installed as early as 1941. Gordon W. Scott’s window would be installed above the spot where our organ now stands but that was, at the time, earmarked for a list of names originally compiled in 1929 by the Men’s Association. This list would more than triple in size by 1945. It is to Gordon’s window, the ultimate dedication of the War Memorial in 1949, and the laying to rest of regimental flags in 1951 that we will turn next week.